Medellin, Colombia — Venezuela’s interim President Delcy Rodriguez last week announced plans to release political prisoners from the infamous El Helicoide detention center and transform the architectural marvel-turned alleged torture center in Caracas into a cultural hub, sparking mixed reactions from Venezuelans.

While families of imprisoned dissidents are cautiously optimistic that their loved ones will soon be freed, critics fear the government’s plans could whitewash the memory of atrocities perpetrated there by the regime of Nicolás Maduro.

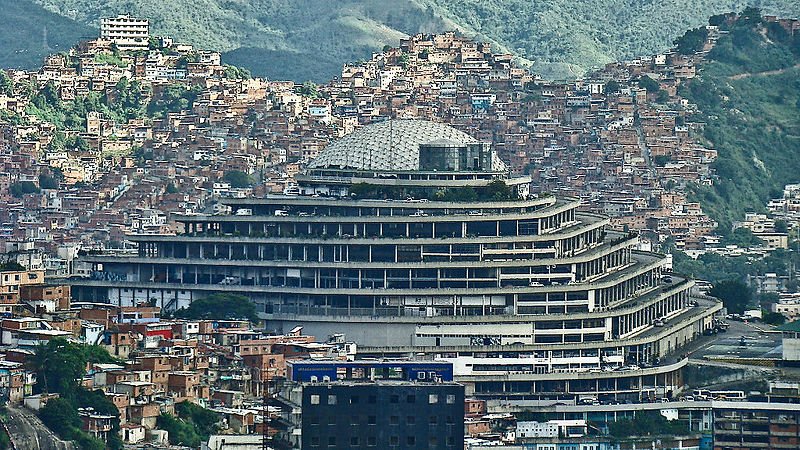

Initially conceived in 1956 as a futuristic shopping mall and symbol of the nation’s modernity by then dictator Marcos Pérez Jiménez, following his overthrow two years later the project stalled. From the 1980s the government began to occupy the building as an administrative centre, eventually housing the headquarters of SEBIN, the Bolivarian National Intelligence Service.

In more recent memory, the towering structure has served as a fearful symbol of state repression visible throughout Caracas. Its miles of reinforced concrete designed to allow consumers to drive to shop doors were converted into overcrowded cells that hold prisoners to this day.

Human rights groups and the testimonials of former prisoners have denounced not only the political nature of some detentions, but also unsanitary conditions, overcrowding, and torture. A 2023 United Nations report found “reasonable grounds to believe” that the 2021 death of General Raúl Isaías Baduel, a former defense minister imprisoned for alleged corruption, was the result of a refusal of adequate medical care. Another report investigated the cases of over 90 victims of human rights violations between 2014 and 2021, with former SEBIN employees stating that Maduro gave direct orders instructing them to torture detainees.

The decision to free prisoners at the site has been met with reserved optimism from human rights NGOs and families of the incarcerated. Foro Penal, which keeps a tally of political prisoners in the country, reported there were still over 600 people being held in El Helicoide after some 400 were released since January 8. That number differs vastly from the government’s claim that it has released 900 so far.

The number of prisoners released could increase following the National Assembly’s unanimous approval of the first vote of an amnesty bill on February 5, which would benefit political dissidents imprisoned since 1999. During the announcement of the bill on January 31, Rodríguez also shared plans for El Helicoide to be transformed into a “cultural, sport, and commercial centre” for the benefit of local communities.

Families of the imprisoned have since gathered outside the prison in anticipation of their loved ones’ release. Whilst some have celebrated the announcement, others have criticized the slow pace of releases, accusing the government of prolonging the suffering of families.

The proposal to convert El Helicoide into a cultural centre has also been met with criticism from those who are concerned it could erase the prison’s violent past. “For a democratic transition it is fundamental to preserve historical memory,” Rosmit Mantilla, former National Assembly member and previous detainee, told RFI. For him the prospect of converting El Helicoide into a recreational centre is “very dangerous”.

The planned changes would not be the first time the state has been accused of attempting to distract from the building’s use as a prison. Last May Transparencia Venezuela denounced the use of El Helicoide for a professional basketball league over a “dungeon of political prisoners.”

Alí Daniels, a lawyer and director of Aceso a la Justicia, a Venezuelan NGO that monitors human rights and the justice system, believes the future of the building should be geared towards education and the promotion of historical memory.

Noting the symbolic nature of El Helicoide, Daniels believes that its structure should be maintained but as “a symbol of peace and coexistence” that simultaneously recognizes its history and those responsible for it.

For Daniels, the seriousness of the building’s history “makes it necessary for it to become one of the first steps in establishing a construction of Venezuela’s historical memory” and therefore shouldn’t be distorted, but instead turned into a place for education.

“It should be a museum of memory where future generations are taught what happened there […] to vindicate all those who have been victims,” he said.

Featured image: El Helicoide

Image credit: Damián D. Fossi Salas via Wikimedia Commons. License: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0/