In a public hospital in São Paulo’s north zone, Carnival arrives with soft shoes and careful timing. A troupe of clowns turns pediatric corridors into a brief street parade, testing how joy, discipline, and health care can share space.

A Bloco at the Pediatric Door

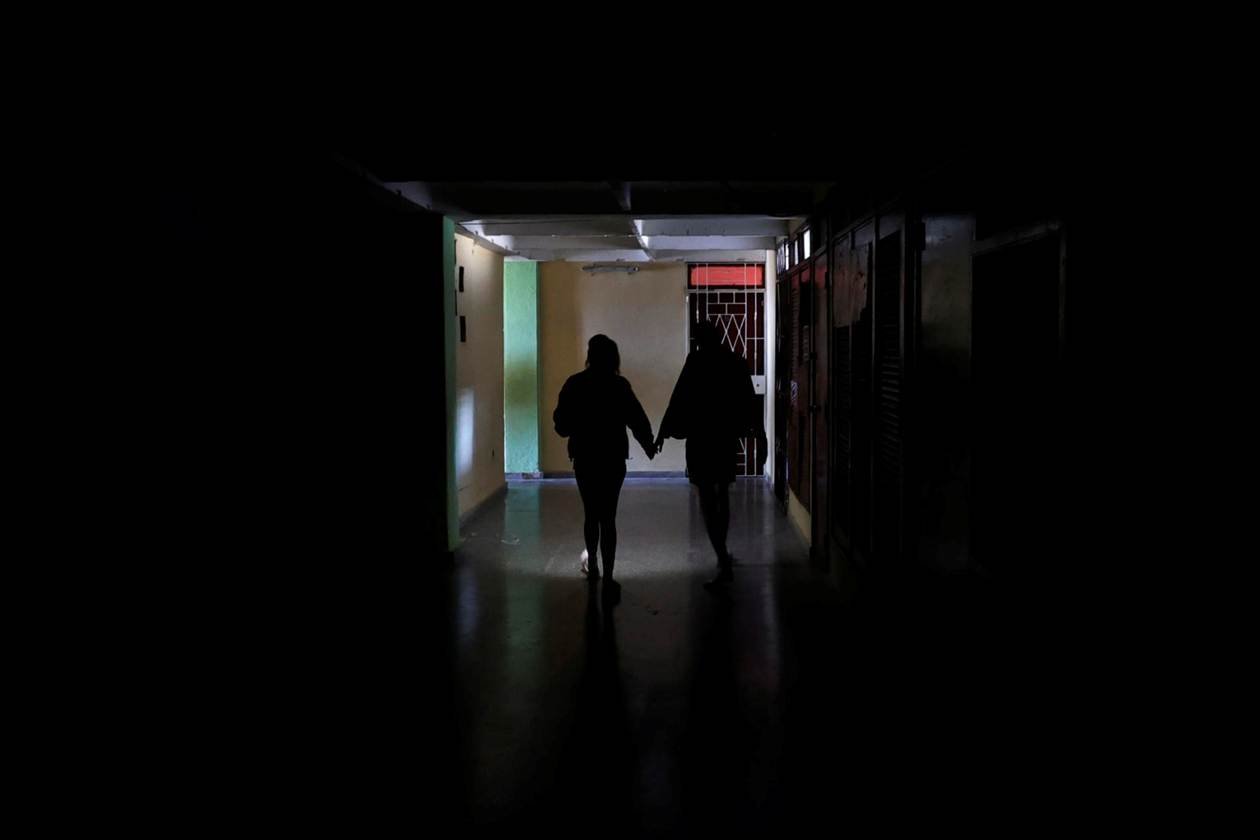

The hall usually has its own soundtrack. Rubber soles whispering on linoleum. The steady, impatient beep of monitors. A door opening and closing with the hush of routine. But in Carnival season, the silence gives way, and what enters is bright, organized mischief.

A police officer guarding the entrance to the pediatric sector spots one of the Doctors of Joy arriving in plain clothes and says, with what sounds like relief, “What’s going on?” “We thought you were not coming. We were waiting for you,” the officer told EFE.

That small exchange, at a doorway that separates the hospital from the rest of the day, sets the tone. In Brazil, not even hospitals sit out Carnival. Still, nothing here is casual. The trouble is that joy, in a place built for pain and waiting, has to be handled like medicine. Wrong dosage, wrong timing, and it becomes too much.

The Doctors of Joy is an NGO made up of artists trained in clowning. For about twenty years, they have visited this public hospital twice a week. This time, they come for something special, to bring their bloco, a Carnival parade that has spent nine years moving through São Paulo hospitals. They call this one Riso Froxo, and their logic is simple: in a corridor where infection and anxiety travel easily, let the contagious thing be a smile.

Cavaco, also known as Anderson Machado, is forty and one of twelve clowns in the group. He jokes about compresses and hurry, playing with the sound of words. The joke lands precisely because everyone here understands the stakes. Nurses who have been moving from room to room with professional focus, eyes behind glasses, pause. For a while, they trade their regular gear for color. Glasses come off, masks go on. A stethoscope is set aside. Cardboard ties appear like an absurd badge of temporary permission.

Then the music hits the corridor. Classic Carnival rhythms, but with lyrics aimed at health. The building does not become a theater. It becomes something harder to define. A hospital that remembers it is full of people, not just cases.

The Child Behind the Diagnosis

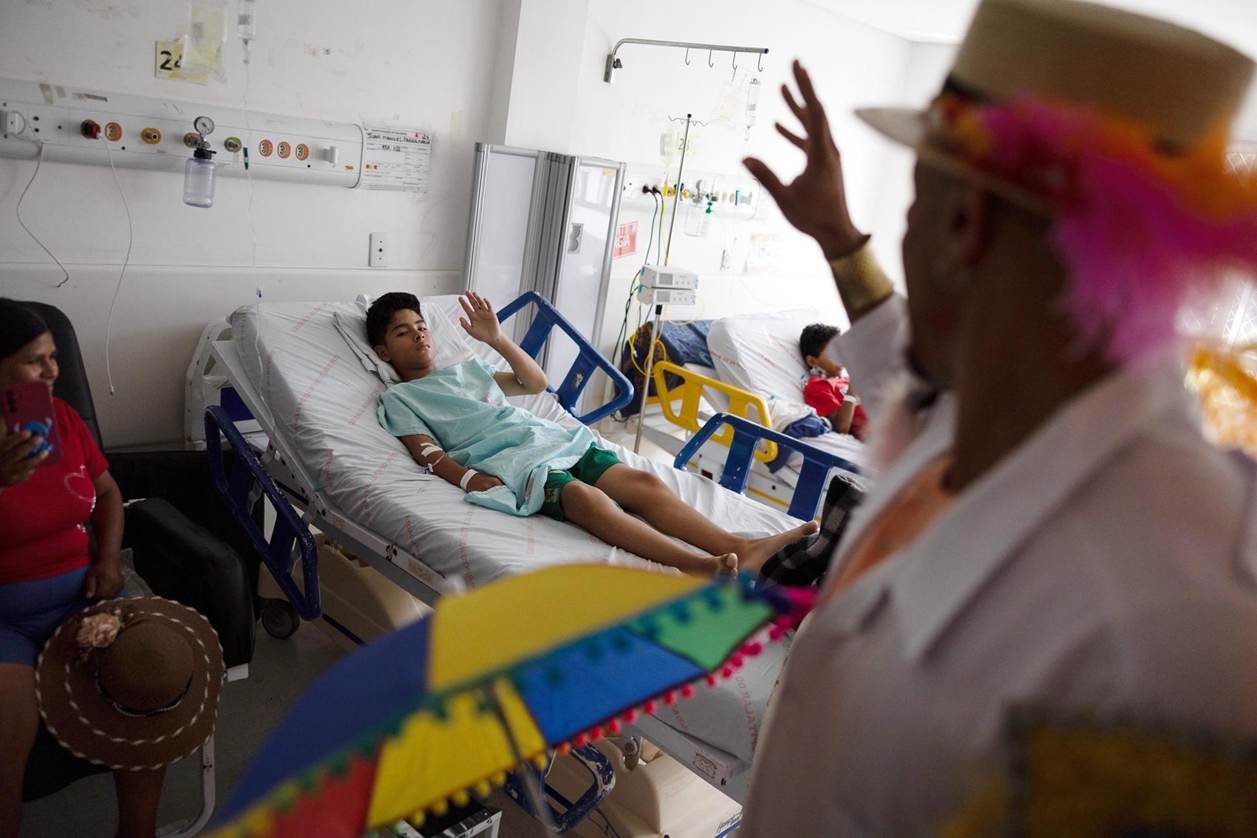

From down the hall, the drums arrive first, and a child reacts before anyone says a word. A boy starts bouncing at his doorway beside his mother. She holds the IV pole with one hand and records on her phone with the other, catching the moment the clowns spill into the wing like a controlled wave of color.

Natali Barbosa is thirty-three. She is there with her eight-year-old son, Wendell, who is fighting a severe infection. The parade hits her in a way she does not try to hide. “I felt like crying. Whether you want to or not, it is a little difficult for children to go through this. The show gave them a boost, a joy. Not only them, but us too,” she told EFE.

It is a straight line from that sentence to the policy dispute that lives inside hospital culture. Who is the hospital for? What is treatment meant to do? How much of healing is clinical, and how much depends on emotional weather?

Guadalupe, the clown played by actress Tereza Gontijo, is thirty-nine, and she names the problem most plainly. When a child enters a hospital, she says, the child is reduced to a diagnosis. People begin to interact with him through what he has and what treatment he needs. The Doctors of Joy, she says, work with the healthy side of the person beyond the illness.

“Behind that diagnosis, there is a person. Behind a health professional, there is a person. Behind the role of mother, there is a person,” she told EFE. “We do not come to cure, but to work the healthy side, despite everything else.”

This is not a sentimental claim. It is an operational one. It asks the hospital staff to loosen, for a moment, the grip of pure procedure and remember what those procedures are trying to protect. The wager here is that a small shift in atmosphere can change how a day feels, and how a day feels can change how a child copes, how a mother holds up, how a nurse returns to the next room.

You can see it without anyone announcing it. Faces soften. Shoulders drop. A corridor that had been only a transit becomes a place where people stop.

Clean Faces Before Painted Smiles

The parade looks spontaneous, but it is built on almost clinical preparation.

Before the music starts, the clowns come with clean faces. No paint. No performance voice. They talk to doctors, gather information, learn how many patients are in each area, and ask about each child’s condition. They do it because this is not a stage and they are visitors in a space of discomfort. The hospital has its own rules and its own fragility.

Backstage is a small ritual. As they tint their eyelids with color, getting ready to go on, they warn each other about the child in the first room with a broken bone. They celebrate the discharge of a patient they remember for an unusual brightness. Even their excitement comes with a quiet check, a reminder that everything here has a boundary.

Tereza explains it as an art of arriving. You do not enter the room of a baby in intensive care the same way you approach a seventeen-year-old. The voice changes. The volume changes. The level of animation is adjusted with precision. The point is not to invade. It is to invite the child and the family into play.

Nearby, psychologist Márcia Prado watches the environment shift as health professionals join the procession, even without being at its center. You get the sense that the clowns not only affect the children. They give the adults permission to be human in a place that often forces them into roles.

Social worker Fátima Grilo, who has been at the institution for more than twenty-five years, ties it back to outcomes without overpromising. Treatment, she says, seems to evolve better when emotions are better. One of the questions she hears most is simple and repeated, almost like a schedule request in another kind of crisis.

When are the clowns coming?

In a corridor where time is measured in shifts, doses, and waiting, that question is its own small vote of confidence. Not in spectacle. In presence. In the idea that Brazil’s biggest celebration can enter a hospital without disrespecting its pain, and still leave something useful behind.

Also Read:

Venezuelan Firefighter Turns Dominican Jet Set Tragedy Into Protocol Lessons Today