Birds are perhaps the most colorful group of animals, bringing a splash of color to the natural world around us every day. Indeed, exclusively black and white birds—such as magpies—are in the minority.

However, new research by a team from Princeton University in the United States has revealed a surprising trick in which birds use those boring black and white feathers to make their colors even more vivid.

In the study, published today in Science Advances, Rosalyn Price-Waldman and her colleagues discovered that if colored feathers are placed over a layer of either white or black underlying feathers, their colors are enhanced.

A particularly striking discovery was that in some species the different color of males and females wasn’t due to the color the two sexes put into the feathers, but rather in the amount of white or black in the layer underneath.

Why birds are so bright—and how they do it

Typically, male birds have more vivid colors than females. As Charles Darwin first explained, the most colorful males are more likely to attract mates and produce more offspring than those that aren’t as vivid. This process of “sexual selection” is the evolutionary force that has resulted in most of the colors we see in birds today.

Evolution is a process that rewards clever solutions in the competition among males to stand out in the crowd. Depositing a layer of black underneath patches of bright blue feathers has enabled males to produce that extra vibrancy that helps them in the competition for mates.

The reason the black layer works so well is that it absorbs all the light that passes through the top layer of colored feathers. The color we see is blue because those top feathers have a fine structure that scatters light in a particular way, and reflects light in the blue part of the spectrum.

The feathers appear particularly vivid blue because the light in other wavelengths is absorbed by the under-layer. If the under-layer was paler, some of the light in the other parts of the light spectrum would bounce back and the blue would not “pop out” as much.

Different tricks for different colors

Interestingly, in the new study, the researchers found that for yellow feathers the opposite trick works. Yellow feathers contain yellow pigments—carotenoids—and in this case they are enhanced if they have a white under-layer.

The white layer reflects light that passes through the yellow feathers, and this increases the brightness of these yellow patches, making them more striking in contrast to surrounding patches of color.

A surprisingly common technique

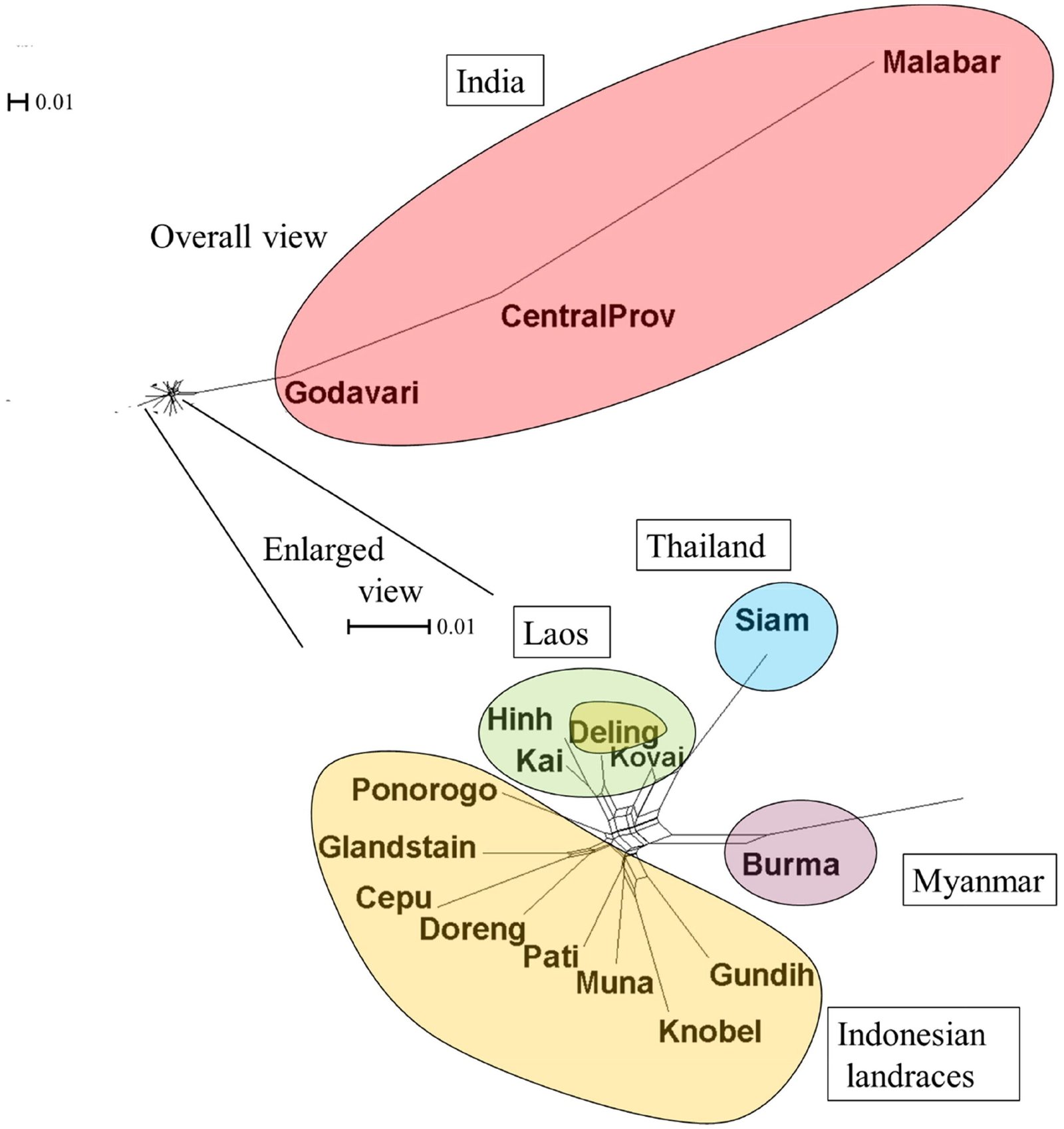

The authors focused most of their work on species of tanager, typically very colorful fruit-eating birds that are native to Central and South America.

However, once they had discovered what was happening in tanagers, they checked to see if it was occurring in other birds.

This additional work revealed that the use of black and white underlying feathers to enhance color is found in many other bird families, including the Australian fairy wrens, which have such vivid blue coloration.

This widespread use of black and white across so many different species suggests birds have been enhancing the production of color in this clever way for tens of millions of years, and that it is widely used across birds.

The study is important because it helps us to understand how complex traits such as color can evolve in nature. It may also help us to improve the production of vibrant colors in our own architecture, art and fashion.

More information:

Rosalyn M. Price-Waldman et al, Hidden white and black feather layers enhance plumage coloration in tanagers and other songbirds, Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adw5857

Provided by

The Conversation

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.![]()

Citation:

Hidden black and white feathers found to intensify blue and yellow bird plumage (2025, July 26)

retrieved 26 July 2025

from https://phys.org/news/2025-07-hidden-black-white-feathers-blue.html

This document is subject to copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of private study or research, no

part may be reproduced without the written permission. The content is provided for information purposes only.