Geneva correspondent

BBC

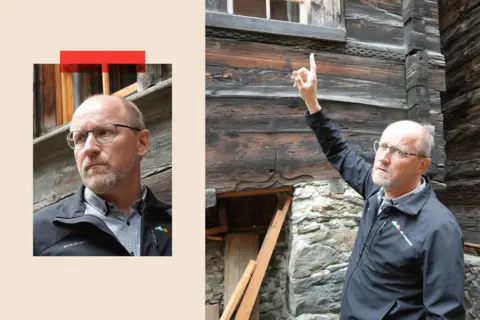

BBCIn a small village in Switzerland’s beautiful Loetschental valley, Matthias Bellwald walks down the main street and is greeted every few steps by locals who smile or offer a handshake or friendly word.

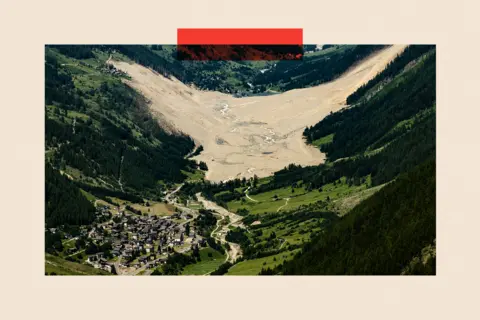

Mr Bellwald is a mayor, but this isn’t his village. Two months ago his home, three miles away in Blatten, was wiped off the map when part of the mountain and glacier collapsed into the valley.

The village’s 300 residents had been evacuated days earlier, after geologists warned that the mountain was increasingly unstable. But they lost their homes, their church, their hotels and their farms.

Lukas Kalbermatten also lost the hotel that had been in his family for three generations.”The feeling of the village, all the small alleys through the houses, the church, the memories you had when you played there as a child… all this is gone.”

Hotel Edelweiss

Hotel EdelweissToday, he is living in borrowed accommodation in the village of Wiler. Mr Bellwald has a temporary office there too, where he is supervising the massive clean-up operation – and the rebuild.

The good news is, he believes the site can be cleared by 2028, with the first new houses ready by 2029. But it comes with a hefty pricetag.

Rebuilding Blatten is estimated to cost hundreds of millions of dollars, perhaps as much as $1 million (USD) per resident.

Voluntary contributions from the public quickly raised millions of Swiss francs to help those who had lost their homes. The federal government and the canton promised financial support too. But some in Switzerland are asking: is it worth it?

Shutterstock

ShutterstockThough the disaster shocked Switzerland, some two thirds of the country is mountainous, and climate scientists warn that the glaciers and the permafrost – the glue that holds the mountains together – are thawing as the global temperature increases, making landslides more likely. Protecting areas will be costly.

Switzerland spends almost $500m a year on protective structures, but a report carried out in 2007 for the Swiss parliament suggested real protection against natural hazards could cost six times that.

Is that a worthwhile investment? Or should the country – and residents – really consider the painful option of abandoning some of their villages?

The day the earth shook

The Alps are an integral part of Swiss identity. Each valley, like the Loetschental, has its own culture.

Mr Kalbermatten used to take pride in showing hotel guests the ancient wooden houses in Blatten. Sometimes he taught them a few words of Leetschär, the local dialect.

Losing Blatten, and the prospect of losing others like it, has made many Swiss ask themselves how many of those alpine traditions could disappear.

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieToday, Blatten lies under millions of cubic metres of rock, mud, and ice. Above it, the mountain remains unstable.

When they were first evacuated, Blatten’s residents, knowing their houses had stood there for centuries, believed it was a purely precautionary measure. They would be home again soon, they thought.

Fernando Lehner, a retired businessman, says no one expected the scale of the disaster. “We knew there would be a landslide that day… But it was just unbelievable. I would never have imagined that it would come down so quickly.

“And that explosion, when the glacier and landslide came down into the valley, I’ll never forget it. The earth shook.”

Landslides are ‘more unpredictable’

The people of Blatten, keen to get their homes back as soon as possible, don’t want to talk about climate change. They point out that the Alps are always dangerous, and describe the disaster as a once in a millennium event.

But climate scientists say global warming is making alpine life more risky.

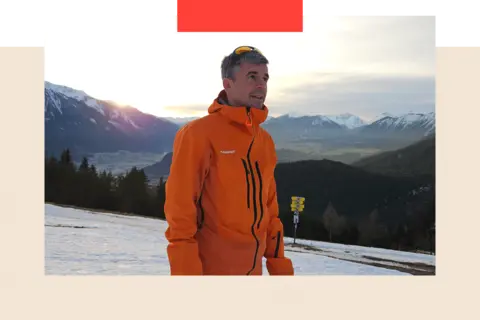

Matthias Huss, a glaciologist with Zurich’s Federal Institute of Technology, as well as glacier monitoring group Glamos, argues that climate change was a factor in the Blatten disaster.

“The thawing of permafrost at very high elevation led to the collapse of the summit,” he explains.

Matthias Huss

Matthias Huss“This mountain summit crashed down onto the glacier… and also the glacier retreat led to the fact that the glacier stabilised the mountain less efficiently than before. So climate change was involved at every angle.”

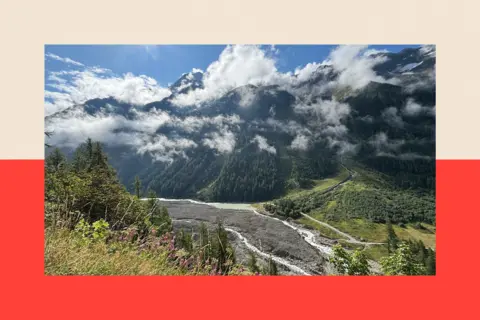

Geological changes unrelated to climate change also played a role, he concedes – but he points out that glaciers and permafrost are key stabilising factors across the alps.

His team at Glamos has monitored a record shrinkage of the glaciers over the past few years. And average alpine temperatures are increasing.

In the days before the mountain crashed down, Switzerland’s zero-degree threshold – the altitude at which the temperature reaches freezing point – rose above 5,000 metres, higher than any mountain in the country.

“It is not the very first time that we’re seeing big landslides in the Alps,” says Mr Huss. “I think what should be worrying us is that these events are becoming more frequent, but also more unpredictable.”

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieA study from November 2024 by the Swiss Federal Research Institute, which reviewed three decades of literature, concurred that climate change was “rapidly altering high mountain environments, including changing the frequency, dynamic behavior, location, and magnitude of alpine mass movements”, although quantifying the exact impact of climate change was “difficult”.

More villages, more evacuations

Graubünden is the largest holiday region in Switzerland, and is popular with skiers and hikers for its untouched nature, alpine views and pretty villages.

The Winter Olympics was hosted here twice – in the upmarket resort of St Moritz – while the town of Davos hosts world leaders for the World Economic Forum each year.

One village in Graubünden has a different story to tell.

Brienz was evacuated more than two years ago because of signs of dangerous instability in the mountain above.

Its residents have still not been able to return, and in July heavy rain across Switzerland led geologists to warn a landslide appeared imminent.

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieElsewhere in Switzerland, above the resort of Kandersteg, in the Bernese Oberland region, a rockface has become unstable, threatening the village. Now residents have an evacuation plan.

There too, heavy rain this summer raised the alarm, and some hiking trails up to Oeschinen Lake, a popular tourist attraction, were closed.

Some disasters have claimed lives. In 2017, a massive rockslide came down close to the village of Bondo, killing eight hikers.

Bondo has since been rebuilt, and refortified, at a cost of $64 million. As far back as 2003, the village of Pontresina spent millions on a protective dam to shore up the thawing permafrost in the mountain above.

Not every alpine village is at risk, but the apparent unpredictability is causing huge concern.

The debate around relocation

Blatten, like all Swiss mountain villages, was risk mapped and monitored; that’s why its 300 residents were evacuated. Now, questions are being asked about the future of other villages too.

In the aftermath of the disaster, there was a huge outpouring of sympathy. But the possible price tag of rebuilding it also came with doubts.

An editorial in the influential Neue Zürcher Zeitung questioned Switzerland’s traditional – and constitutional – wealth distribution model, which takes tax revenue from urban centres like Zurich to support remote mountain communities.

The article described Swiss politicians as being “caught in an empathy trap”, adding that “because such incidents are becoming more frequent due to climate change, they are shaking people’s willingness to pay for the myth of the Alps, which shapes the nation’s identity.”

It suggested people living in risky areas of the Alps should consider relocation.

Preserving the alpine villages is expensive. And Neue Zürcher Zeitung was not the first to question the cost of saving every alpine community, but its tone angered some.

While three quarters of Swiss live in urban areas, many have strong family connections to the mountains. Switzerland may be a wealthy, highly developed, high-tech country now, but its history is rural, marked by poverty and harsh living conditions. Famine in the 19th century caused waves of emigration.

Mr Kalbermatten explains that the word “heimat” is hugely important in Switzerland. “Heimat is when you close your eyes and you think about what you did as a child, the place you lived as a child.

“It’s a much bigger word than home.”

Ask a Swiss person living for decades in Zurich or Geneva, or even New York, where their heimat is, and for many, the answer will be the village they were born in.

For Mr Kalbermatten and his sister and brothers, who live in cities, heimat is the valley where people speak Leetschär, the dialect they all still dream in.

Imogen Foulkes

Imogen FoulkesThe fear is that if these valleys become depopulated, other aspects of unique mountain culture could be lost too – like the Tschäggättä, traditional wooden masks, unique to the Loetschental valley.

Their origins are mysterious, possibly pagan. Every February, local young men wear them, along with animal skins, and run through the streets.

Mr Kalbermatten points to the example of some areas of northern Italy where this loss of culture has happened. “[Now] there are only abandoned villages, empty houses, and wolves.

“Do we want that?”

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieFor many, the answer is no: An opinion poll from research institute, Sotomo, asked 2,790 people what they most cherished about their country. The most common answer? Our beautiful alpine landscape, and our stability.

But the poll did not ask what price they were prepared to pay.

Trying to tame a mountain

Boris Previsic, the director of the University of Lucerne’s Institute for the Culture of the Alps, says that many Swiss, at least in the cities, had begun to believe they had tamed the alpine environment.

Switzerland’s railways, tunnels, cable cars and high alpine passes are masterpieces of engineering, connecting alpine communities. But now, in part because of climate change, he suggests, that confidence is gone.

“The human induced geology is too strong compared to human beings,” he argues.

“In Switzerland, we thought we could do everything with infrastructure. Now I think we are at ground zero concerning infrastructure.”

Boris Previsic

Boris PrevisicThe village of Blatten had stood for centuries. “When you are in a village which has existed already for 800 years, you should feel safe. That is what is so shocking.”

In his view, it is time to fight against these villages dying out. “To fight means we have to be more prepared,” he explains. “But we have to be more flexible. We have always also to consider evacuation.”

At the end of the day, he adds, “you cannot hold back the whole mountain”.

In the village of Wiler, Mr Previsic’s point is greeted with a weary smile. “The mountain always decides,” agrees Mr Bellwald.

“We know that they are dangerous. We love the mountains, we don’t hate them because of that. Our grandfathers lived with them. Our fathers lived with them. And our children will also live with them.”

Angus MacKenzie

Angus MacKenzieAt lunchtime in the local restaurant in Wiler, the tables are filled with clean-up teams, engineers and helicopter crew. The Blatten recovery operation is in full swing.

At one table, a man from one of Switzerland’s biggest insurance companies sits alone. Every half hour, he is joined by someone, an elderly couple, a middle aged man, a young woman. He buys each a drink, and carefully notes down the details of their lost homes.

Outside, along the valley’s winding roads, lorries and bulldozers trundle up to the disaster site. Overhead, helicopters carry large chunks of debris. Even the military is involved.

Sebastian Neuhaus commands the Swiss army’s disaster relief readiness battalion, and says they must press on despite the scale of the task. “We have to,” he says. “There are 300 life histories buried down there.”

The abiding feeling is one of stubborn determination to carry on. “If we see someone from Blatten, we hug each other,” says Mr Kalbermatten.

“Sometimes we say, ‘it’s nice, you’re still here.’ And that’s the most important thing, we are all still here.”

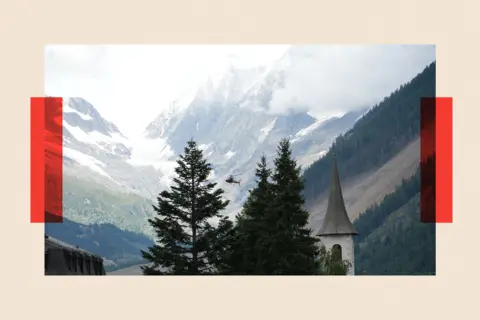

Lead image: The village of Blatten after the disaster. Credit: EPA / Shutterstock

BBC InDepth is the home on the website and app for the best analysis, with fresh perspectives that challenge assumptions and deep reporting on the biggest issues of the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content from across BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You can send us your feedback on the InDepth section by clicking on the button below.