These days, there’s a global obsession with all things Korean, from K-pop and K-dramas to skincare routines and sizzling Korean BBQ. In the Mexico City neighborhood where I live — technically Roma Norte, but close to Zona Rosa’s Little Seoul — Korean restaurants have multiplied in the 18 months since I’ve lived here, to my great delight, I might add.

But did you know that Mexico has had a Korean diaspora since the early 1900s? It was 120 years ago this year that the first wave of Koreans set foot on Mexican soil. In this piece, we’ll explore the fascinating and tragic story of that migration and what followed.

A forgotten migration story

In 1904, global power struggles and economic demands set the stage for an unlikely migration. Korea was increasingly under Japan’s control, though official annexation wouldn’t come until a few years later. Meanwhile, Mexico was in the last years of the President Porfirio Díaz dictatorship, and the Yucatán Peninsula faced a labor shortage as global demand surged for henequén, an agave plant used to make rope and twine.

To meet that demand, a Japanese firm partnered with a British labor recruiter to bring Korean workers to Mexico under misleading terms. Newspaper ads in Korea described Yucatán as a land of opportunity. They promised free transport to Mexico, housing, access to land, education for children, healthcare and a guaranteed return home.

The reality, however, would turn out to be grim.

At the time, Korean emigration outside Asia had only just begun. In 1902, laborers were first sent to work on sugar plantations in Hawaii. But by 1905, Japan began limiting Korean migration to the U.S., worried it threatened Japanese laborers and would increase anti-Japanese sentiment in places like California.

As a result, Mexico — with no prior diplomatic ties to Korea and no existing Korean population — became the next destination for migrant labor. This was driven more by Japan’s imperial interests than by any bilateral agreement.

From hope to hard labor

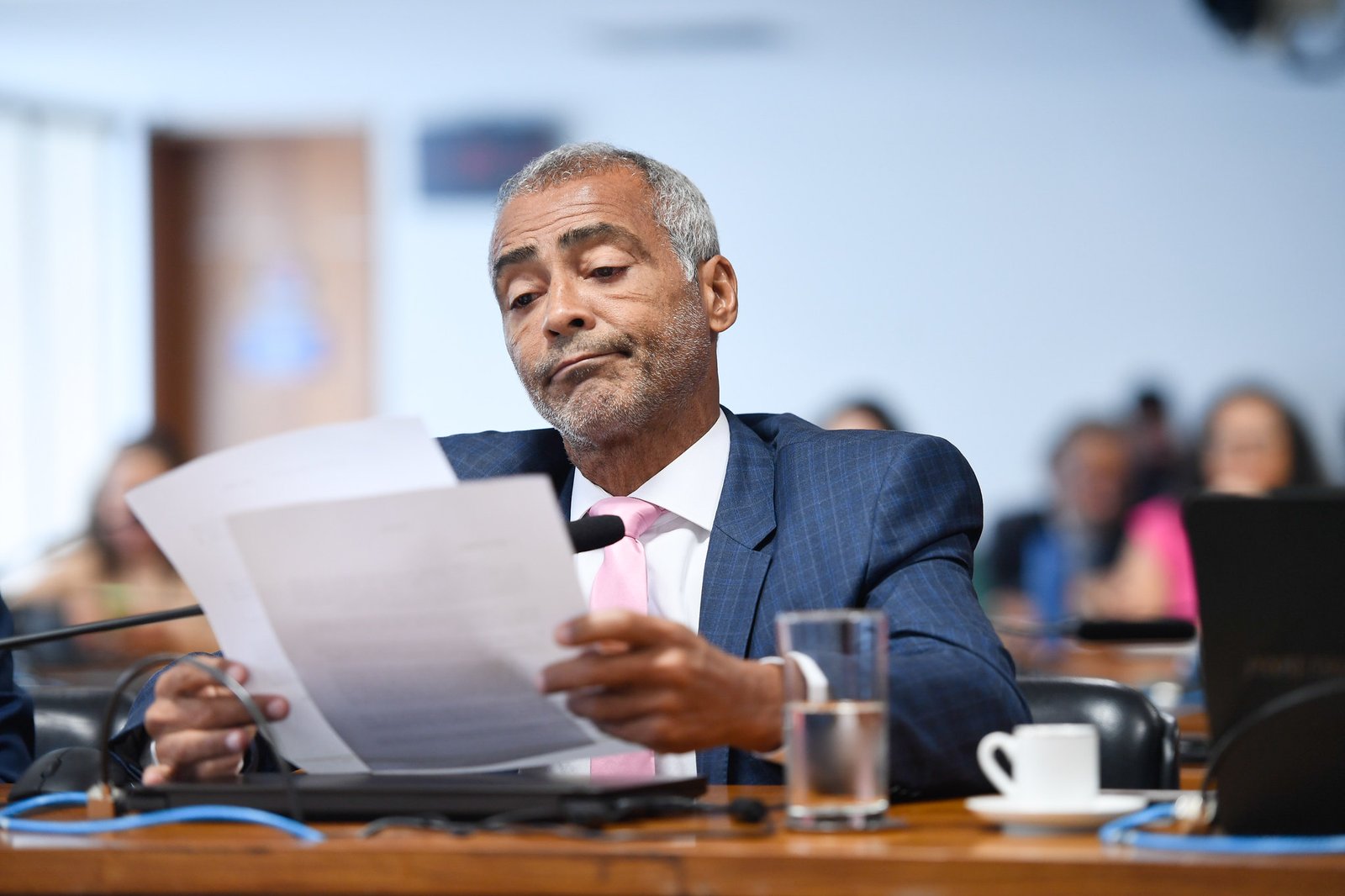

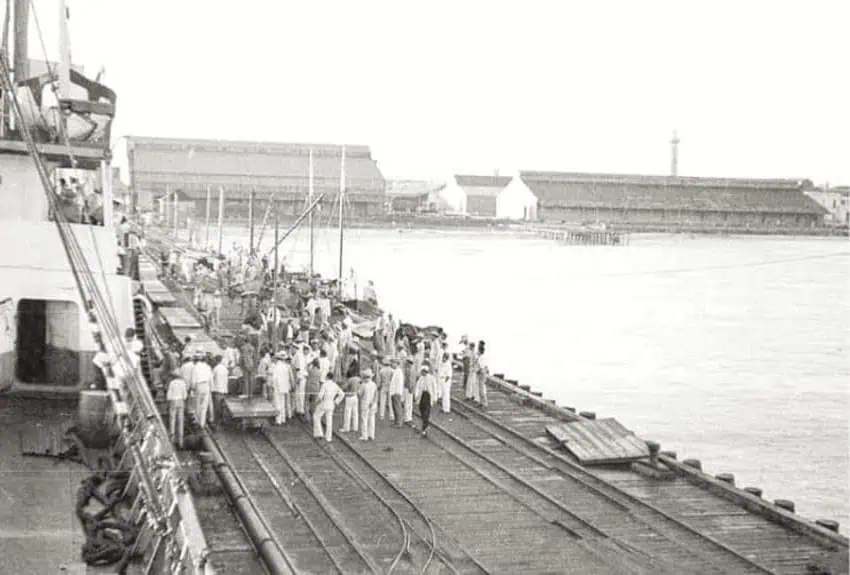

On May 4, 1905, over 1,000 Koreans disembarked at the port of Salina Cruz, Oaxaca, after a long trans-Pacific voyage aboard the SS Ilford. They had left an impoverished and unstable Korea for a better life in Mexico. Instead, they were sold as indentured laborers to henequén plantation owners in Yucatán.

They were quickly absorbed into Mexico’s deeply exploitative hacienda system. What had been promised as a five‑year contract with fair conditions — almost a dream opportunity for the time — turned into a grueling and punishing reality. Laborers worked long hours in extreme conditions harvesting henequén — referred to as “green gold” — without any of the promised benefits.

Many Korean workers were scattered across vast plantations with no access to Korean-language schools, churches or community networks. Isolated from one another and cut off from their culture, they found themselves working side by side with Indigenous Maya laborers, who were also subjected to the same brutal labor conditions.

Over time, the Korean men began to adopt elements of Maya life. Some learned Mayan before Spanish and formed deep bonds with the local communities. Intermarriage between Koreans and Maya became common. As families formed, a unique cultural fusion emerged. The descendants of these unions grew up immersed in Maya traditions, Catholic festivals and local customs while the Korean language and identity slowly faded.

By the time their contracts ended in 1910, Korea had been formally annexed by Japan, and the Mexican Revolution was erupting. There was no home to return to, and few viable alternatives. Many stayed in Yucatán; others left to find work elsewhere in Mexico or in Cuba.

Aenikkaeng: Reclaiming a buried identity

Descendants of those original migrants eventually came to call themselves Aenikkaeng, a term derived from the Korean pronunciation of “henequén.” It’s a word that captures both the hardship and the legacy of their ancestors’ experience.

For decades, this history remained buried. It wasn’t until the 1970s that South Korean researchers, diplomats and journalists began visiting Yucatán to trace the descendants of the SS Ilford’s 1905 passengers. Their efforts aligned with South Korea’s broader push to strengthen ties with Latin America, and the rediscovery of the Aenikkaeng story took on historical and diplomatic importance.

In 2005, the centennial of Korean immigration to Mexico was commemorated in Mérida with a monument inscribed with the names of the original 1905 laborers. Two years later, the Museum of Korean Immigration to Yucatán (MCICY) opened with support from both the Mexican and South Korean governments.

Yet, for many descendants, cultural identity remained complicated. Those interviewed during centennial celebrations often described feeling Korean in name only. Their lives were shaped by the land they grew up in — by Maya roots, Mexican traditions and generations of adaptation.

A cultural revival

In recent years, there have been growing efforts to reconnect with that lost heritage. Local organizations like the Asociación Coreano-Mexicana have launched language courses, genealogy projects and heritage trips to South Korea. Some younger Aenikkaeng descendants have traveled to Seoul or Incheon, seeking work there or trying to understand the culture their ancestors left behind.

In 2017, Korean-Argentine photographer Michael Vince Kim released a striking photo series documenting Aenikkaeng descendants in Yucatán and Cuba. His portraits offered an intimate glimpse into a little-known community, honoring the memory of those early migrants and the quiet endurance of their families. The series, like the people it portrayed, is both powerful and understated — a visual tribute to a legacy long overlooked.

The story of Koreans in Mexico is still missing from most textbooks and public discourse. While the experiences of other Asian migrant communities have been recognized, the Korean story remains largely absent from Mexico’s national narrative. For the Aenikkaeng, recognition is long overdue — but it’s slowly beginning to arrive.

Koreans in Mexico today

Approximately 13,000 ethnic Koreans now live in Mexico, with the largest communities in Mexico City, Guadalajara and Monterrey. In Mexico City, the area informally known as Little Seoul thrives with Korean restaurants, grocery stores and businesses, a vibrant counterpoint to the first wave of laborers who arrived in 1905 and the product of a newer migration surge tied to South Korean corporate expansion in the 1990s. Mexico City has become a hub of Korean restaurants, grocery stores and businesses, reflecting a very different kind of Korean migration.

I live just a few blocks from there, and it’s one of my favorite things about the neighborhood. After spending time in South Korea, there’s something comforting about being able to pick up gochujang nearby or sit down for a good bowl of kimchi jjigae. It’s a reminder of a place and time that still feels close — just in a different context.

Rocio is a Mexican-American writer based in Mexico City. She was born and raised in a small village in Durango and moved to Chicago at age 12, a bicultural experience that shapes her lens on life in Mexico. She’s the founder of CDMX IYKYK, a newsletter for expats, digital nomads, and the Mexican diaspora, and Life of Leisure, a women’s wellness and spiritual community.