In 2024, 2.6 billion people – nearly a third of humanity – remained offline, the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) reported. The same year, non-profit Freedom House estimated that more than three-quarters of those who had internet access lived in countries where people were arrested for posting political, social or religious content online, and almost two-thirds of all global internet users were subject to online censorship.

This should bother us, because whether people have internet access and the quality of that access matter deeply for what kind of life they can live. Free and unimpeded internet access is no longer a convenience or a luxury.

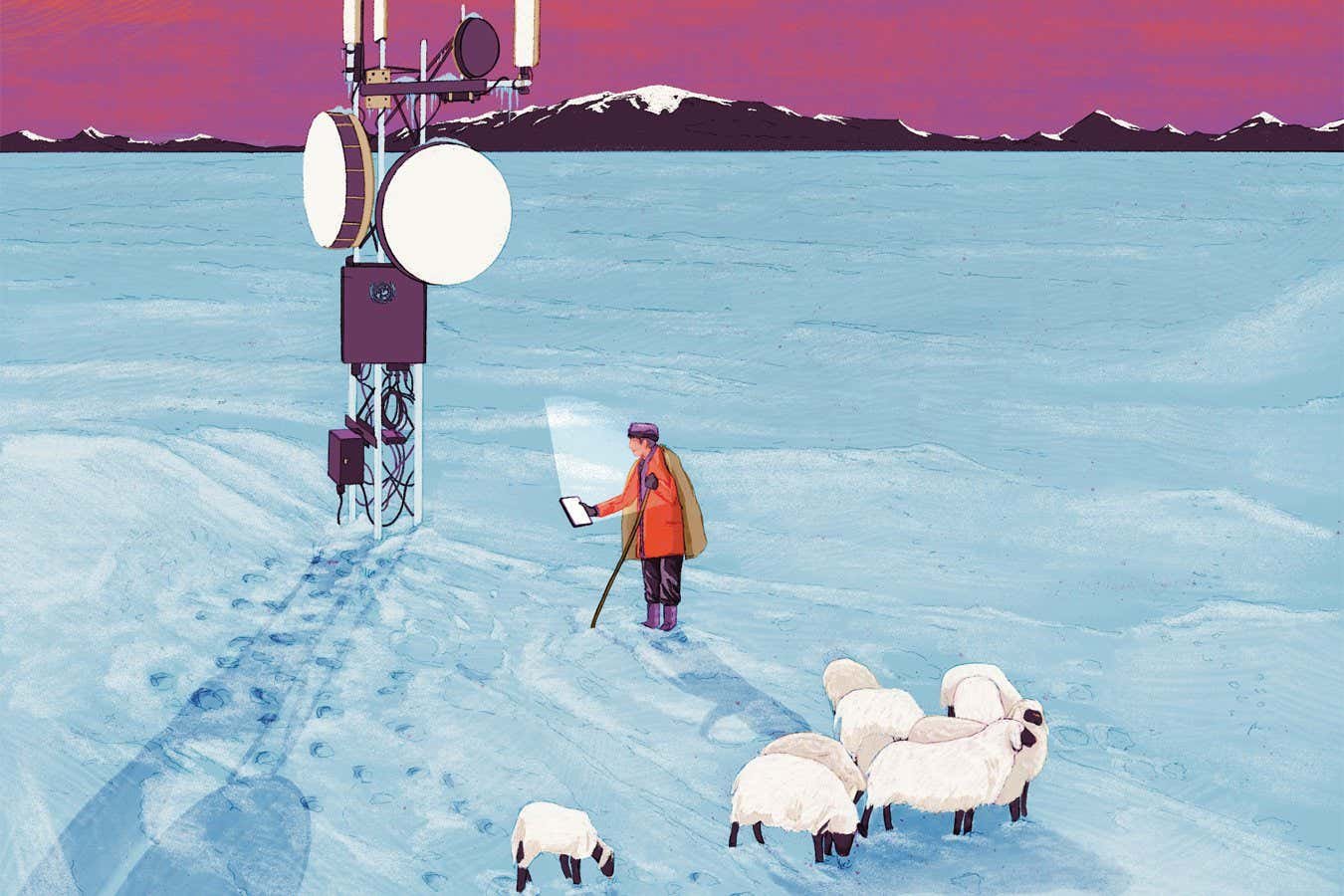

Human rights, as first set out by the United Nations General Assembly in a milestone document in 1948, ensure that we can live minimally decent lives. But in our digitised world, people’s opportunities to exercise their human rights to everything from free speech to free primary education are all significantly determined by their access to the internet. For example, access to many public services has moved online, and in some places online services are the most feasible alternatives to absent brick- and-mortar banks, schools and healthcare facilities.

That fundamental importance to life today means that free access to the internet now needs to be recognised as a standalone human right by the UN and nation states. This recognition would provide a guarantee backed by international law, and obligations of international financial support where nations end up falling short.

The ITU estimates that it would cost nearly $428 billion to establish universal broadband coverage by 2030. That is a large sum. However, connecting the rest of humanity would have enormous benefits, as it would allow people to become better educated, more economically active and healthier.

In fact, guarantees of a minimum level of connectivity are already feasible goals: providing people with 4G mobile broadband network coverage, permanent access to a smartphone, affordable data that costs no more than 2 per cent of monthly gross national income per capita for 2GB and opportunities for acquiring basic digital skills.

But only internet access of a certain quality is beneficial for human rights and, as the UN has argued, contributes to the “progress of humankind as a whole“. When the internet is used to monitor populations to identify opposition to political power, to collect private data to maximise profits, or to misinform and generate interpersonal strife, it becomes a technology of repression rather than of empowerment. Recognising a human right to internet access creates duties of protection for national governments.

This right would demand that states respect internet users’ privacy, instead of spying on them, censoring information or manipulating through online propaganda. It would demand that businesses respect people’s human rights, particularly the right to privacy, rather than obtaining a plethora of personal information. And it would call for the regulation of social media, forcing corporations to fight disinformation and abuse on their platforms.

In 2016, the UN recognised that “‘rights that people have offline must also be protected online”. But it didn’t recognise a standalone human right to free internet access, despite this first being proposed as a possibility in 2003.

It is now time to act. Above all, a human right to free internet access is a call to political action. We cannot afford to lose the fight for the internet as a medium that promotes human progress, rather than one that undermines it. Establishing this right would provide a powerful resource for ensuring that the internet benefits everyone, rather than a select few.

Merten Reglitz is a philosopher and author of Free Internet Access as a Human Right

Topics: