In Minnesota, beavers have long been considered a nuisance, thanks to their uncanny ability to gnaw trees and construct dams that sometimes clog culverts, raise lake levels or flood roads.

But among scientists, there’s a growing recognition that these toothy engineers actually bring a host of environmental benefits. Their dams slow water flow, reduce flooding and create critical wetlands that boost biodiversity — and can even slow wildfires.

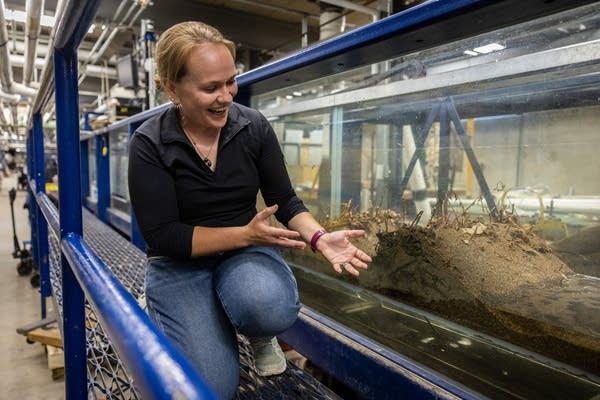

“We oftentimes only consider them as a pest or as a nuisance because they are really powerful and really chaotic,” said Emily Fairfax, an assistant professor at the University of Minnesota, who specializes in beaver research. “They’re second only to us in their ability to change the physical earth. And we both want to live in flood plains. We both want to control the water.”

A new outdoor stream channel planned for the St. Anthony Falls Laboratory, on Hennepin Island in Minneapolis, will allow Fairfax and other researchers to study how beaver dams function and change the surrounding landscape.

Minnesota likely has more than 100,000 beaver dams, yet Fairfax says there hasn’t been a lot of research on beavers.

“We know everything about people-built dams, and we know so little about the true hydraulics of a beaver dam,” she said. “And that matters a lot in somewhere like Minnesota.”

Understanding how beaver dams function and affect the surrounding floodplain also will help scientists better understand their role in resisting pollution, floods and wildfires.

When beavers build dams, they also dig little canals that help spread the water out onto the landscape. That allows it to seep slowly into the soil, filtering out nutrients and keeping plants lush and green. If a wildfire comes through, beaver wetlands are often too wet to burn.

And unlike humans, beavers are tireless maintenance crews that show up every day to make repairs, Fairfax said.

“They are absolutely determined to keep the water there. It is life or death for them,” she said. “A beaver on land is extraordinarily vulnerable … A beaver in the water is almost invincible. So their whole life is about maintaining a wetland environment.”

Beaver-created wetlands provide habitat for fish, birds and other wildlife. They also provide extra water storage, which makes the land more resilient to flooding and drought.

“It’s not like beavers waddle out there and are like, ‘I’m going to solve the climate crisis,’” Fairfax said. “They’re just going about their lives. And it just so happens that the things they do really strongly benefit us.”

Just a fraction of the beavers that once roamed North America still remain. During the fur trade, their population plummeted to near extinction. It has since recovered, but is nowhere near historical numbers.

Several western U.S. states have already embraced beaver restoration as a method of reducing wildfire risk. Minnesota has been slower to shift its philosophy, said Andy Riesgraf, a research scientist at the St. Anthony Falls Lab.

“Out west, it was almost kind of like a need,” he said. “You need more water on the landscape, or more stored water because of these mega fires or droughts.”

In the Upper Midwest, attitudes toward the industrious rodents are slowly beginning to change, Riesgraf said.

“With that comes learning about ways to coexist with beavers, instead of trapping and killing them — which is the method for dealing with problem beavers right now in Minnesota,” he said.

Still, beaver restoration would require a shift in public attitudes, and finding ways for humans and beavers to share control of water.

Fairfax and Riesgraf are working on nonlethal management strategies, such as fencing around culverts or installing devices to control water levels.

“It’s really just if we can figure out how to work alongside them strategically and without constantly butting heads,” Fairfax said. “Because we are both very powerful, very intent and very stubborn on controlling the rivers.”

Research at the outdoor beaver stream at St. Anthony Falls Lab will begin next fall. Visitors will be able to watch as it’s happening, and learn more about how the furry ecosystem engineers can help fight climate change.

Fairfax has spent years sloshing through wetlands in chest waders and using drones and satellite images to collect data on beaver dams. But the outdoor stream at St. Anthony Falls Lab will allow researchers to experiment with how beaver dams react to droughts and floods, and what it takes for one to fail.

Beavers tend to build a series of dams called a complex. If one breaches, the next one can catch the water, Fairfax said.

“We’ve seen them withstand 100-year floods, 500-year floods,” she said. “They’re designed to flex. They’re designed to be overtopped. They’re designed to have water go around and under and over and through.”

Fairfax also teaches people how to build beaver dam “analogs” — human-made structures that resemble real ones. She recently returned from building mock dams near Dubuque, Iowa, where the goal is to kick-start stream restoration by creating better conditions for real beavers to move in.

Before a career shift, Fairfax previously worked at Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico as a nuclear weapons engineer. She said she finds beavers fascinating — and relatable. Both human and beaver engineers use concepts like physics and hydrology to control water flow, she said.

And Fairfax said there’s another appeal: Beavers are one of the few organisms in nature that offer a narrative of hope and resilience, amid dire stories of climate disasters and environmental degradation.

“It’s the easiest solution. They’re just waddling around. They’re all up and down the Mississippi,” she said. “We just have to let them be beavers.”