A son of prominent South African anti-apartheid activist Steve Biko has told the BBC the family is confident a new inquest into his death 48 years ago will lead to the prosecution of those responsible.

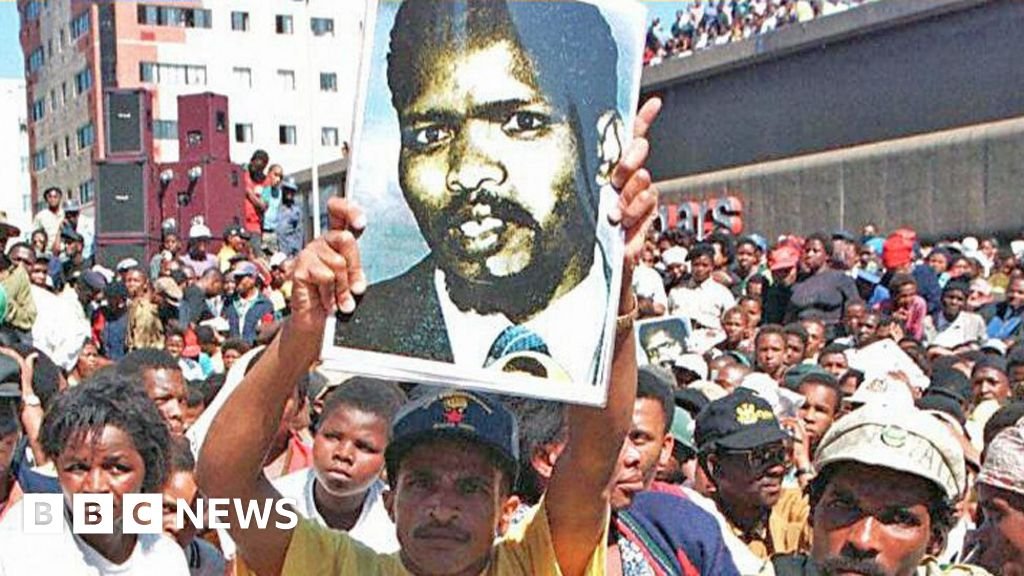

Seen as a martyr in the struggle against white-minority rule, the Black Consciousness Movement founder died from a brain injury aged 30 almost a month after being arrested at a roadblock.

Police at the time said he had banged his head against a wall, but after apartheid ended in 1994, former officers admitted to assaulting him – although no-one has been prosecuted.

Nkosinathi Biko, who was six when his father died, said the country could not move forward without addressing its violent past.

“It’s very clear in our minds as to what happened and how they killed Steve Biko,” he told the BBC after the first hearing was held at the High Court in the southern city of Gqeberha – on the 48th anniversary of his father’s death.

It is alleged that Biko, who had been subject to a “banning order” that restricted his movements and other activities at the time of his arrest in 1977, was tortured by five policemen while in detention.

“What is required from this process is simply to follow the facts, and we have no doubt that a democratic court, in a democratic state, will find that Steve Biko’s murder was an act, orchestrated and executed by those who were with him – the five policemen who are implicated in this case,” his son said.

On Friday, the judge heard that two people linked to the case remain alive, both now in their 80s.

Biko’s death caused outrage in South Africa and was the subject of the 1987 Hollywood film Cry Freedom, starring Denzel Washington.

He had been a medical student at the University of Natal when he founded the Black Consciousness Movement, aimed at empowering and mobilising the urban black population.

He was determined to combat the psychological inferiority that many black South Africans felt after years of white-minority rule and at a time when anti-apartheid activists like Nelson Mandela had been silenced and incarcerated by the regime.

The new inquest comes five months after President Cyril Ramaphosa announced a judicial inquiry into allegations of political interference in the prosecution of apartheid-era crimes.

The Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC), set up in 1996, uncovered apartheid-era atrocities like murder and torture, but few of these cases progressed to trial.

Biko’s case was heard at the TRC, which is where the policemen involved admitted to having made false statements 20 years earlier, but they were not prosecuted.

“Accountability for our violent, brutal past is something that has evaded South African society,” said Nkosinathi Biko.

“You cannot have the trauma that we had, the flow of blood in the streets orchestrated by a state against a people, and then you emerge with less than a handful of prosecutions ever being successfully made.”

He said families who felt let down by the lack of prosecutions that had been recommended by the TRC had continued to pressure the government for justice.

“You can’t give root to a democracy without dealing with some of the historical issues decisively,” he said.

The case was adjourned until 12 November.