September 16, 2025

4 min read

Readers Respond to the May 2025 Issue

Letters to the editors for the May 2025 issue of Scientific American

Scientific American, May 2025

SPEEDY COMETS

“Dark Comets,” by Robin George Andrews, describes a group of objects in our solar system with “unexplained” acceleration. That made me wonder: Is it possible that while dark energy appears uniform over galactic scales, it is actually more discrete at smaller scales such as that of the solar system? And if such packets of dark energy were to occur near or on one of these “dark comets,” could they be giving those unusual bodies the mysterious acceleration? I guess that wouldn’t really answer anything until we better understand dark energy, but it would be a place to look for clues.

MICHAEL K. MARTIN VIA E-MAIL

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Andrews’s article notes that the cause of the observed acceleration of some items passing through our solar system is unclear. The article considers whether outgassing might induce the acceleration, but no strong evidence for this option has been found. Unconsidered is another possible influence relating to magnetic fields.

An object that is made up of fused metals might accumulate an electrical charge. A charged item that travels through strong magnetic fields, as could be encountered close to the sun or Jupiter, might be expected to display acceleration without any visible emissions. Has anyone done the calculations to see if this might account for some of the anomalous acceleration?

SCOTT T. MEISSNER VIA E-MAIL

ANDREWS REPLIES: Seeing as dark energy appears to be responsible for accelerating the expansion of the universe, it’s not unreasonable to wonder whether it’s giving certain comets an extra speed boost, too. But Martin is right: we don’t really understand dark energy, so invoking it to explain these weird zigzagging objects is probably a dead end—and I’m not sure dark energy operates on such a specific and tiny scale.

I like Meissner’s idea that these objects might be pushed by an electromagnetic force! One issue, though, is that of composition: highly metallic asteroids, including ones like Psyche (which is potentially an exposed iron core from a destroyed planet), don’t appear to be affected by the magnetic field of the sun or Jupiter in this way. So this is probably not the explanation for dark comets.

MINING THE SEAFLOOR

I read “Deep-Sea Mining Begins,” by Willem Marx, with anger. It seems the problem of deep-sea mining is not only an economic or political one; it is also an ethical and moral one. Too many people think only of their own livelihood. They care about their present lives but not about Earth’s future. We must boost our society’s moral standards.

HIROYUKI UCHIDA TOKYO

REPTILE CALIBRATION?

“Turtle Dance,” by Jack Tamisiea [Advances], observes that loggerhead sea turtles dance when they find food and also form lifelong memories of Earth’s magnetic field specific to such feeding grounds. If a sea turtle can navigate with our planet’s magnetic field, it must have a magnetic sensor. It seems likely to me that a sea turtle’s “dance” creates the lifelong memory by finding which body orientation maximizes the response in its magnetic sensor, similar to the calibration of a magnetic fluxgate compass.

JAMES R. McGEE LAKE ELMO, MINN.

WHALE OF A PROBLEM

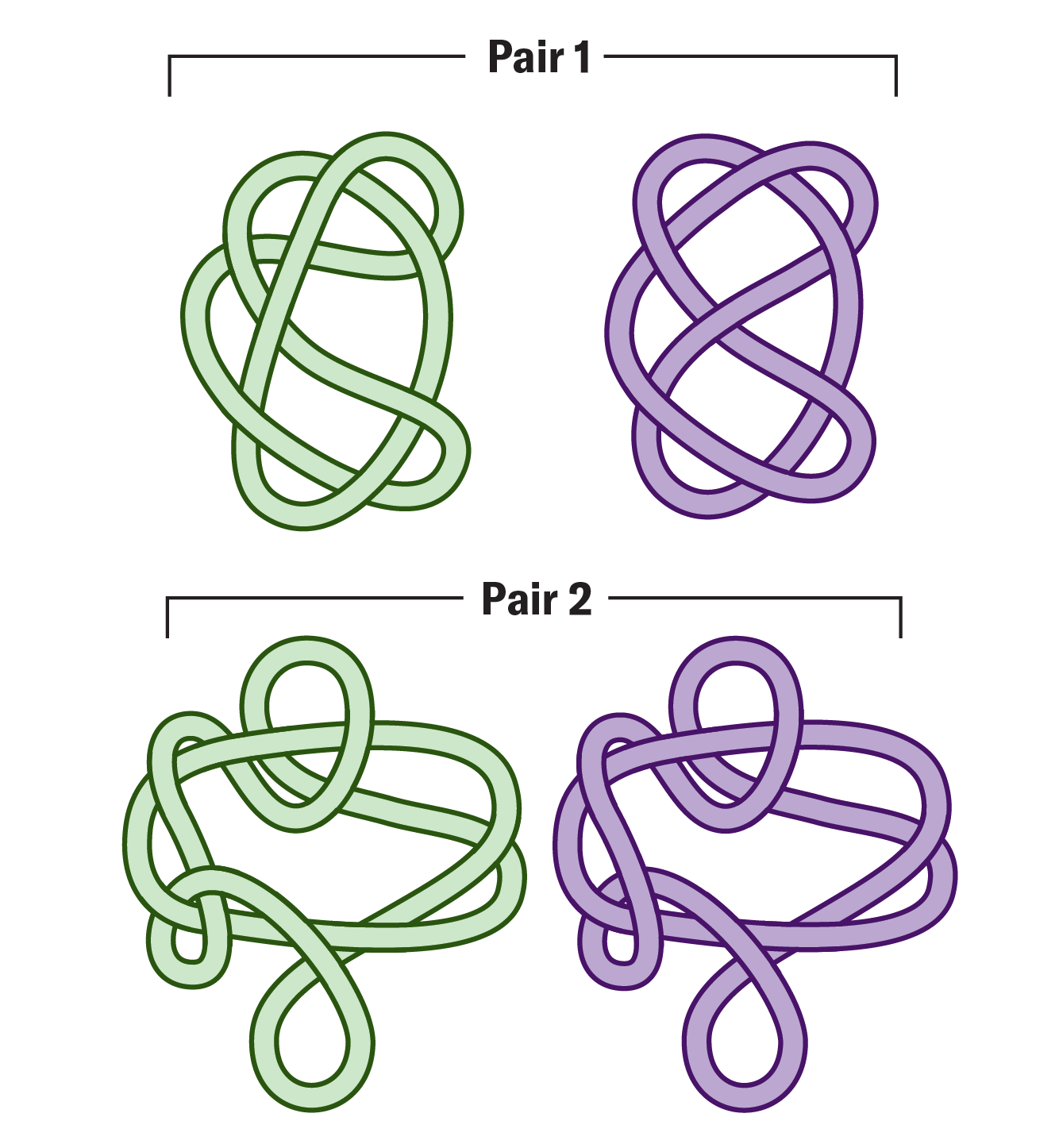

“Shape Shift,” by Rachel Crowell and Violet Frances, presents mathematicians’ descriptions of beautiful and intriguing forms and surfaces. Among them, Sarah Hart of Birkbeck, University of London, discusses cycloids—curves traced out by a point on a circle’s circumference as it rolls along a line—and describes an interesting property concerning the descent of a particle along a cycloid: under gravity, the particle “will reach the bottom in the same time no matter where on the curve it is released.”

I wonder whether Hart is aware that in Herman Melville’s 1851 novel Moby-Dick, the character of Ishmael observes and empirically solves this very problem while scrubbing a large iron pot used to render oil from whale blubber: “I was first indirectly struck by the remarkable fact, that in geometry all bodies gliding along the cycloid, my soapstone for example, will descend from any point in precisely the same time.” Melville was an intuitive mathematician and an extremely acute observer of everything.

“CWITHAL” VIA E-MAIL

GENDER AND OPPRESSION

In “Romantic Hopes” [Advances; June], Clarissa Brincat reports on a review of past studies that suggests that men place more importance on romantic relationships than women do because they “expect to gain more.” The article quotes psychologist Mariko Visserman as noting that the paper explains “how gendered norms and experiences early in life can set the stage for the differences between men’s and women’s relationship benefits and vulnerabilities later on.” It is not surprising that early experiences set up adult patterns. What is surprising is that the article never mentions the form of society that produces the cultural “gendered norms” from which those early experiences and relationship patterns arise: patriarchy.

As a now retired psychotherapist with a master of social work degree, I’d say it is no wonder that female expectations of romantic relationships are not very high. Most women are still often harshly judged by men who don’t believe they are entitled to enjoy the same freedoms, including sex, as men do. The gendered norms of patriarchy give rise to men who seek to dominate women and use them as sex objects. Romantic relationships should be fun and exciting for women and men in our sociable species. But from adolescence, women are “hit on” at school, in the workplace and in public with sexual innuendo, ridicule and unwanted sexual advances. This barrage of insults and pressure that approaches or, more likely, is the cultural norm naturally disheartens many women from actively seeking romance. Many women of course still seek romantic relationships, although most are understandably quite guarded and take time to trust. Feminism has been attacked for decades, if not longer.

Your article’s omission of a mention of what seems to be the obvious determinative role of patriarchy in relationships is concerning and suggests the same norms may be at work covertly or overtly in your publication.

ELLIOTT LIBMAN VIA E-MAIL

ERRATUM

In “Dark Comets,” by Robin George Andrews, an image of the asteroid Bennu was incorrectly identified as showing the asteroid Ryugu.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.