This article is part of “Innovations In: Alzheimer’s Disease” an editorially independent special report that was produced with financial support from Eisai.

About four years ago Clifford Harper, then 85, announced to his wife that he was quitting alcohol. Harper wasn’t a heavy drinker but enjoyed a good Japanese whiskey. It was the first of a series of changes Linda Kostalik saw in her husband. After he’d cleared out the liquor cabinet, Harper, a prolific academic who has authored several books, announced he was tired of writing. Next the once daily runner quit going to the gym. Kostalik noticed he also was growing more forgetful.

The behaviors were unusual enough that, at an annual physical, the couple’s physician recommended they consult a neurologist. A battery of medical tests and brain scans revealed that Harper’s surprising actions and memory loss were the result of dementia.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Harper’s neurologist at Oregon Health Sciences University (OHSU) asked whether he might like to enroll in a long-running study of dementia in African Americans. The study’s focus on Black health piqued Harper’s interest, and he decided to participate for as long as he could. “I hope it will help other men like me,” Harper says.

As a Black American, Harper faces a risk of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias that is twice that of white Americans his age. The reasons for this disparity are still unclear, but researchers know Black Americans are particularly vulnerable to a number of confirmed risk factors, such as living in areas with higher rates of air pollution and encountering difficulties accessing healthy foods and high-quality education. Some studies suggest that experiencing racism and other forms of discrimination contributes to a higher risk of cognitive decline. Race or gender discrimination also raises a person’s risk of heart disease and, as a result, some forms of dementia.

That’s part of what prompted Harper to participate in OHSU’s study, called the African American Dementia and Aging Project (AADAPt), which was established in part to capture the unique history and experiences of Black communities in Oregon. The state’s first constitution banned nonwhite citizens from settling there. The ban was overturned by the early 1900s, and shipyard work during World War II brought an influx of Black workers to the region, but they still faced discrimination and racism in many forms. By the end of the war, racist lending practices—called redlining—led most of the Black community to live in segregated neighborhoods or those that were poor in resources needed for good health, such as parks and grocery stores.

Discrimination in the scientific world, along with other factors such as distrust of researchers, led to underrepresentation of Black communities in brain research. Even today clinical trials for new treatments of Alzheimer’s include very few people of color. As a result, researchers and doctors are ill-equipped to understand the causes of dementia in these communities. “Not only are there health disparities around rates of Alzheimer’s, but we’ve understudied the Black population in relation to the causes,” says Andrea Rosso, an epidemiologist at the University of Pittsburgh.

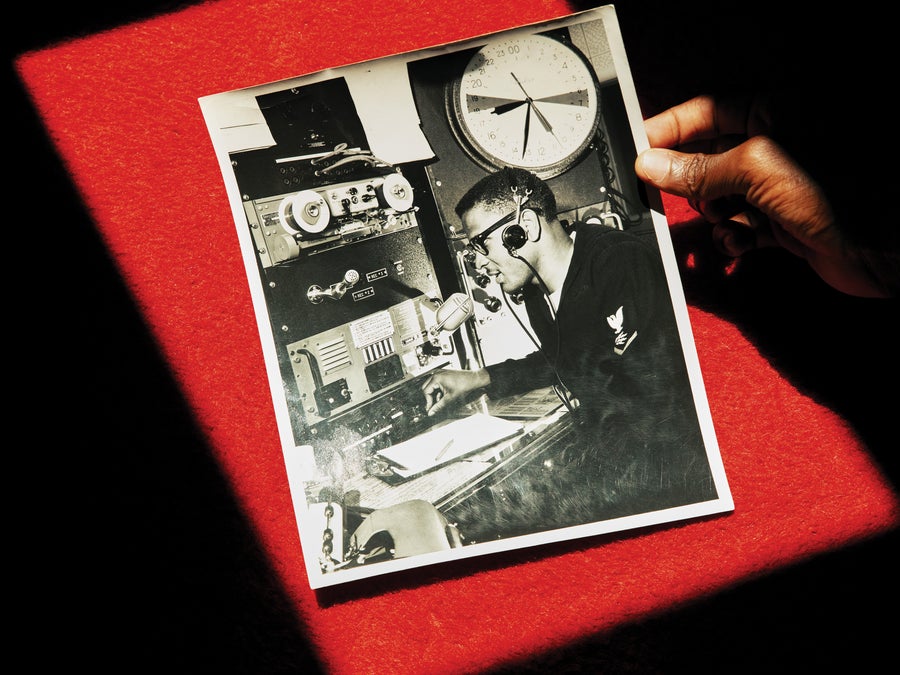

Harper spent years in the U.S. Coast Guard, where he experienced racism and recognized the protection his tight-knit community had offered him throughout his childhood.

Now that Alzheimer’s and some other dementias can be diagnosed early and their progress potentially slowed, figuring out who’s most vulnerable is even more critical. Diagnostic tests and interventions aren’t yet reaching all those who need them. Researchers should include historically minoritized communities in studies of these new frontiers in dementia diagnosis and treatment, says epidemiologist Beth Shaaban of the University of Pittsburgh. If adequate attention isn’t paid to diverse populations, communities that already experience disproportionate rates of dementia will be uninformed about their increased risk, how to lower it and how to access diagnoses and care. “We are very concerned that these disparities and the rapid evolution of the new technology could leave people behind,” Shaaban says.

AADAPt and other studies aim to correct this inequity. The project seeks to understand the forces driving cognitive decline in Black Americans, identify protective factors that lead to healthy aging, and find practical solutions. The team hopes to eventually use the data to build predictive models that will catch cognitive decline early and potentially help people such as Harper access new medicines and treatments via clinical trials.

At the turn of the century researchers projected that an aging baby boomer generation would drastically increase the incidence of Alzheimer’s and other forms of dementia. No treatments or protective strategies were known at the time, and the search for solutions focused largely on the tangles of proteins that jammed up brain circuits.

In the past two decades, scientists have discovered that certain drivers of Alzheimer’s may be controllable. In 2011 dementia researcher Deborah Barnes of the University of California, San Francisco, and her colleagues reported that poor education and smoking—things that could be addressed by behavioral changes and social reform—were among the greatest threats to aging brains. In a 2022 follow-up study, Barnes reported other modifiable risk factors for Alzheimer’s, such as midlife obesity and sedentary lifestyle, which can raise a person’s risk for heart disease.

“People had been so focused on genetics and medications. No one had really been thinking about the potential for prevention,” Barnes says. “It was surprising to a lot of people to realize that these modifiable risk factors really could play a big role.”

Decreased risk can come in many forms. Education is critical, as it nudges the brain to build more—and more resilient—connections between neurons and different parts of the brain. This so-called cognitive reserve can act as a buffer against degeneration as we age, Barnes says, and can preserve brain function even as plaques and protein tangles start to cause disease. Studies suggest that social engagement can also help build this cognitive reserve.

Heart health is crucial, too. High blood pressure, high cholesterol, and other kinds of heart disease can hinder blood circulation and starve the brain, which is a voracious consumer of oxygen and glucose. Although these problems don’t themselves change protein buildup in the brain, they “kind of exacerbate what’s happening there,” Barnes says. “It’s like a double whammy.”

Harper had to fight for the right to earn his Ph.D. in English. He went on to become a playwright, author, theater producer and professor who wrote several books.

Over the years researchers have found many other ways to reduce dementia risk. Improving air quality is a big one. Although the mechanisms are unclear, studies in animals suggest that the ultrafine particles in polluted air infiltrate lung cells to eventually reach blood vessels in the brain or directly affect the brain’s cortex, where Alzheimer’s starts.

In addition to these modifiable threats, certain genetic variants are also linked to a higher risk of developing dementia. Partly because of this range of causes, “dementia” is a broad umbrella term, and how these varied threats converge to cause disease will dictate the form of dementia someone experiences. Alzheimer’s is the most common form, and vascular dementia is a close second. Other conditions, such as Lewy body dementia and frontotemporal dementia, cause similar cognitive symptoms.

Addressing modifiable health risks, such as by improving education or encouraging heart-healthy behaviors, has slowed the rising toll of dementia, Barnes says. But not all communities have benefited equally.

Education quality, pollutant exposure and access to healthy foods are tied closely to where people live. “There’s a number of ways our neighborhoods impact our cardiovascular and brain health,” Rosso says. Historically, Black and Hispanic neighborhoods have been more likely to lack grocery stores. They also had fewer health-care facilities, and their schools had fewer educational resources available to students. Unsafe neighborhoods made it difficult for people to take walks or exercise safely outdoors. Highways and factories—major sources of air pollution—were often constructed in these already disadvantaged areas. And the residents were stuck where they were—discriminatory lending practices prevented them from moving to better-resourced locales.

Harper grew up in a historically redlined area of East St. Louis, Ill., and his health prospects were not initially promising. Yet it was a close community. Harper’s brother-in-law encouraged him to stay in school. So did Charlie, the owner of a dry-cleaning business on the corner where Harper and his friends hung out. Charlie made the boys a promise: “If you go to college, I’ll clean your clothes,” Harper recalls. “He was shocked because most of us did.”

The dry cleaner kept his word. “Charlie didn’t realize that part of our success was because of him,” Harper says.

Although Harper’s career choices nourished his brain, leaving his childhood neighborhood exposed him to more discrimination. During his service in the U.S. Coast Guard, one of his superiors addressed him in a mocking drawl, insinuating that Black people were “slow and dumb,” Kostalik says. Throughout graduate school Harper had to advocate repeatedly to pursue his English degree. “Back in those days, folks like me didn’t find a welcome mat,” he says.

That racism persisted throughout much of Harper’s life. Kostalik says that when Harper was a professor at the University of Illinois, he would visit a nearby federal penitentiary to confer college degrees on inmates who had earned them. On one such occasion, she says, the father of one of the degree recipients approached Harper. “I don’t care who you are or what you’re wearing,” he said. “You’re still a [N-word].” Today Harper doesn’t recall the interaction and doesn’t mind forgetting it. “That’s something I wouldn’t want to remember,” he says.

Studies show that a lifetime of such experiences takes a toll on heart and brain health. Last year researchers analyzed data gathered from nearly 900 families over a 17-year period to understand how discrimination can affect Alzheimer’s risk. Based on interview records and blood samples from 255 Black Americans, they found that those who reported experiencing racism in their 40s and early 50s had higher levels of two blood proteins that serve as biomarkers of dementia.

Researchers are also learning how social interactions can cause biological change. In research presented earlier this year, Shaaban and her colleagues analyzed how blood vessel damage, connections between brain regions, and Alzheimer’s biomarkers such as amyloid and tau proteins varied by race and sex. They found that white men had better connections across brain regions than Black men and both Black and white women in the U.S. White men also tended to have higher levels of amyloid accumulation, whereas the other groups tended to have more signs of vascular disease. “White men are the outliers,” Shaaban says. “We think this has implications for how people think about what these biomarkers mean in different groups of people.”

Linda Kostalik (right) says that this experience has shown her aspects of Harper’s personality she had not previously encountered. “One of the things that I’ve discovered is I’m probably married to the sweetest man in the world, and so it’s not as scary,” Kostalik says.

The results underscore the need for studies that are more representative of the populations that experience dementia, particularly because discrimination is not a risk factor that an individual can control. “You can tell people to exercise more,” Rosso says, “but you can’t tell them not to be discriminated against.”

Harper has been diagnosed with vascular dementia, a form of dementia that is more common in Black men. In addition to memory loss, he started to struggle with balance recently, and he now uses a cane to walk. Harper says years of experiencing racism probably played a part in his diagnosis and symptoms. He had always made the effort to exercise and eat healthily, but he had little control over the discrimination he fought his entire life. “I am the result of being a Black man in this country,” he says. “I have the highest degree you can get. But I’m a Black man.”

The toll of discrimination has been difficult to quantify, in part because those who experience it are often overlooked by scientific research. As a result, understanding how different risk factors contribute to dementia in Black communities is challenging, Rosso says.

Data from AADAPt and other studies offer some clues. In a study published in May, researchers at the University of Wisconsin–Madison analyzed the links between adverse social experiences and vascular injuries in brain tissue.

The team studied 740 brain samples donated to Alzheimer’s research centers. Regardless of race, the brains of people who had lived in disadvantaged neighborhoods or experienced other discrimination over their lifetime were more likely to bear signs of vascular damage, ranging from blocked vessels to hemorrhages.

Gathering such data can help clinicians improve how they measure Alzheimer’s symptoms and track the disease’s progress. Biomarkers do not differ by racial group, Shaaban says. But dementia can develop in different ways, which means two people with the same diagnosis could have different processes at work in their brains: whereas one may have a buildup of amyloid protein, another may experience more symptoms caused by blood vessel disorders. Studying diverse groups will help scientists understand how these biological mechanisms bring about different forms of cognitive decline, Shaaban says. It will also help them identify the best ways to treat, and prevent, Alzheimer’s and related dementias.

At OHSU, the AADAPt investigators track the physical and mental health of participants at annual exams. If they spot signs of cognitive decline, they follow up to offer guidance or a referral to a specialist. They also conduct interviews with participants to understand how social experiences have shaped their health.

In a 2024 study, the AADAPt team reported that nearly three quarters of the subjects self-rated their health as good or excellent. Yet more than 80 percent had high blood pressure, 33 percent had diabetes, and more than 25 percent had a history of stroke. About two thirds of the participants rated their memory as good or excellent. The contrast between their strong sense of optimism and their medical history indicates a mindset that may be “a little bit protective” of brain health as they age, says gerontology researcher Allison Lindauer of OHSU, lead investigator on the study.

Capturing these nuances could help reduce dementia risk in innovative ways. “Identifying protective factors that are salient to these communities is important,” Rosso says. “We don’t want to write off the whole community and be like, well, you don’t all have Ph.D.s, sorry.”

In addition to working on the AADAPt study, OHSU neurologist Raina Croff began to explore whether neighborhood connections could guard against cognitive decline. She was born in the historically redlined Albina district of Portland and remembers it as tight-knit—much like where Harper grew up. “When your community is confined to a certain area, you’re highly dependent on one another, and you can create quite strong social ties,” she says. “You grow strong from within.”

Croff and her colleagues designed several mile-long walks through the Albina district in an effort to encourage exercise and help build social connections. Each trail was marked with signposts sharing news clips, old advertisements and political campaign buttons. Participants in the study, known as SHARP (for “Sharing History through Active Reminiscence and Photo-Imagery”), walked in groups, discussing the signs and reminiscing as they exercised. The result was improved cognitive function in people with mild memory loss, Croff says.

Such projects can help solve many of the inequities created by systemic racism. They also provide a more complete portrait of brain health in minoritized communities: structural racism and a lack of resources can drain people’s cognitive reserves, yet their social connections may act as a potent buffer.

That complete picture is precisely what the AADAPt researchers hope to glean about the brain health of aging Black Americans, Croff says. “Despite the many barriers, we can still feel empowered to change our health. I think that’s important to anybody.”