September 17, 2025

3 min read

Meet the Oldest Dome-Headed Dinosaur Ever Found

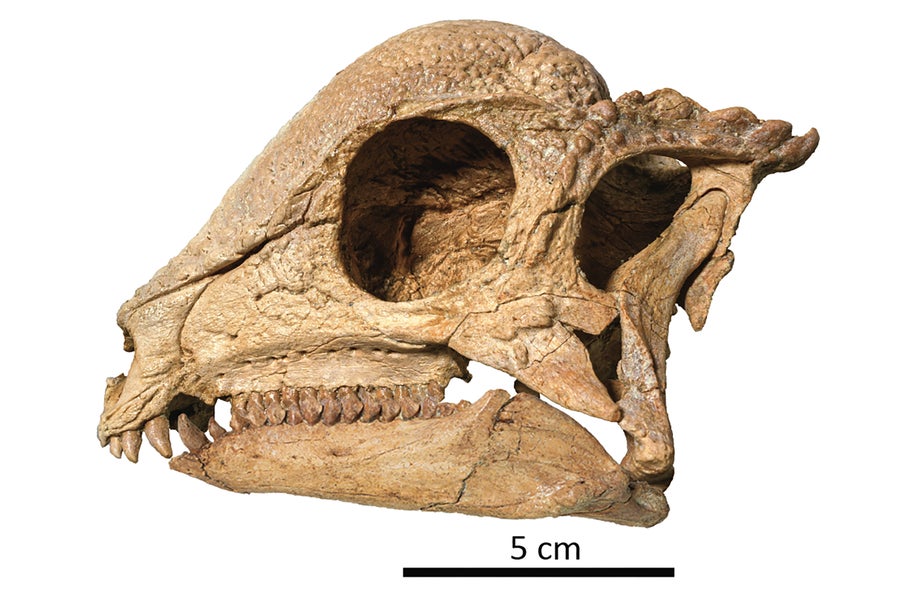

A newly discovered dinosaur species has been identified from a fossil unearthed in Mongolia that represents the most complete pachycephalosaur specimen yet found

Artist’s reconstruction of the newly discovered pachycephalosaur.

Anyone who has ever flipped open a dinosaur book is likely familiar with pachycephalosaurs. These dome-headed dinos are often depicted ramming the tops of their bowling-ball-like skulls into predators or rivals.

Yet despite their popularity, pachycephalosaurs continue to puzzle paleontologists in part because fossils of these bipedal herbivores are rare, says Lindsay Zanno, a paleontologist at North Carolina State University. “The exception is their cranial domes, which were practically indestructible and are usually all we find of these critters,” she says. Almost all of these skull caps date back to the Late Cretaceous, when pachycephalosaurs were already established across the Northern Hemisphere, obscuring the group’s early evolution.

A pachycephalosaur skeleton that was recently discovered in Mongolia is poised to finally fill in the missing chapter of this dinosaur clade’s early history. The remarkably complete fossil, which Zanno and her colleagues described on Wednesday in the journal Nature, represents a new species that is the oldest known dome-headed dinosaurs.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The fossil was unearthed in 2019 in Mongolia’s Gobi Desert, a famed hotbed for dinosaur fossils. While surveying a hillside, Mongolian paleontologist Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig of North Carolina State University and a co-author of the new paper, discovered the top of a dinosaur’s noggin sticking out of a cliff.

The fossil was embedded inside rocks that date to between 115 million and 108 million years ago, in the Early Cretaceous period, when the area was covered by a lush river valley. The team deposited the remarkable find at the Mongolian Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Paleontology, where Tsogtbaatar is also affiliated.

North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences

As the researchers chipped away at the surrounding rock, they quickly realized that the new specimen represented the most complete pachycephalosaur fossil ever discovered. In addition to the rounded skull, the skeleton contains the first record of a pachycephalosaur hand and a complete tail covered with petrified tendons. It even preserves gastroliths—gizzard stones that the animal swallowed to help grind plant material in its digestive tract.

The scientists named the new species Zavacephale rinpoche. The species name is the Tibetan word for “precious one” and refers to the way the skull resembled a rounded, polished gemstone when Tsogtbaatar discovered it.

Zavacephale was a pint-sized pachycephalosaur that weighed roughly as much as a miniature poodle. Despite its diminutive size, the animal possessed a fully developed dome and had likely reached sexual maturity.

Researchers have debated for decades how these dinosaurs used their signature dome. Some have argued that the rounded melons played a role in sexual selection or that they helped species recognize one another. But the most popular interpretation is that the animals used the structure to headbutt one another, as modern bighorn sheep do, which is supported by fossilized skull caps that preserve lesions and other signs of trauma.

The team concluded that Zavacephale represents the oldest known pachycephalosaur and likely originated early on in the evolution of this bizarre group of dinosaurs. “It tells us that the dome head evolved early in pachycephalosaur evolution and arose long before Zavacephale’s bigger, cousins started littering the latest Cretaceous fossil record with their skull caps,” says Stephen Brusatte, a paleontologist at the University of Edinburgh, who was not involved in the new study.

Zavacephale’s cranium had a few noteworthy quirks, however. It was mostly composed of only one skull bone instead of the two bones seen in later species and largely lacked the knobby horns that other pachycephalosaurs had as ornamentation. Brusatte thinks that future finds of early pachycephalosaurs may further reveal how the group’s signature headgear evolved over time.

Zanno agrees. “Zavacephale was just an opening act,” she says, “and now we get to see more of the show.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.