This article is part of “Innovations In: Alzheimer’s Disease” an editorially independent special report that was produced with financial support from Eisai.

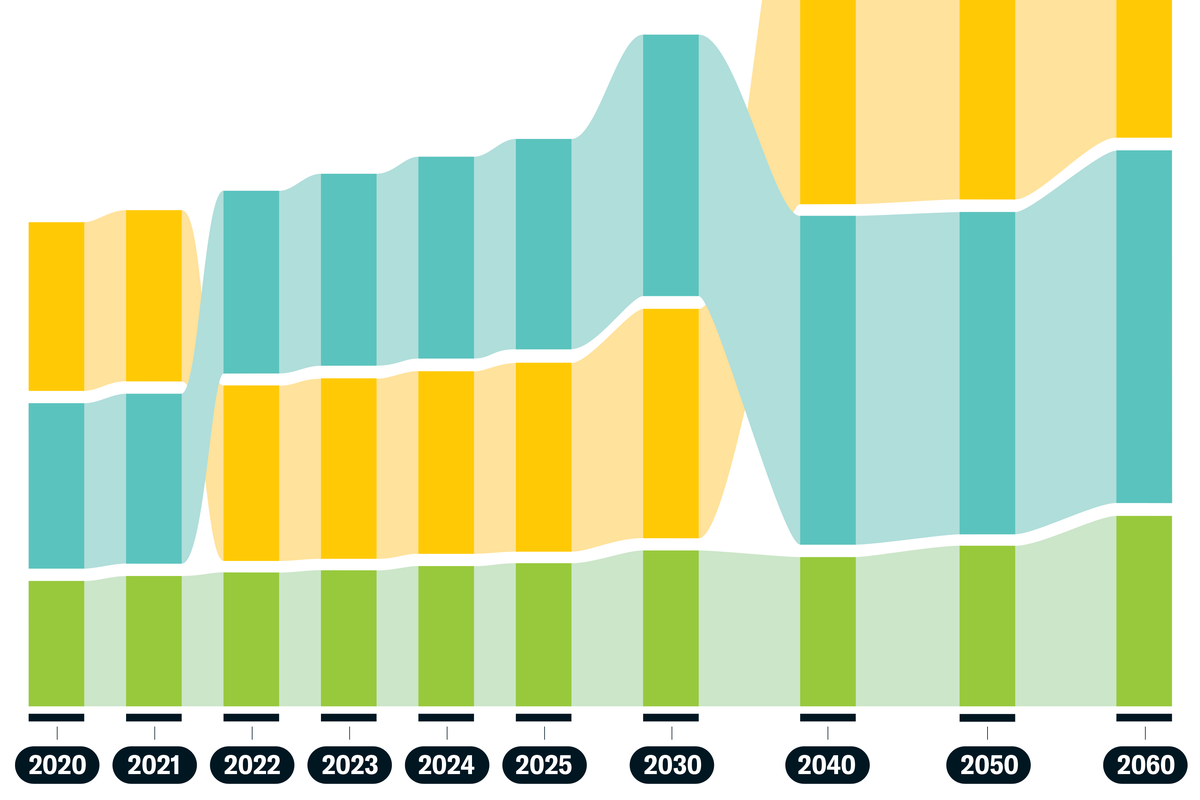

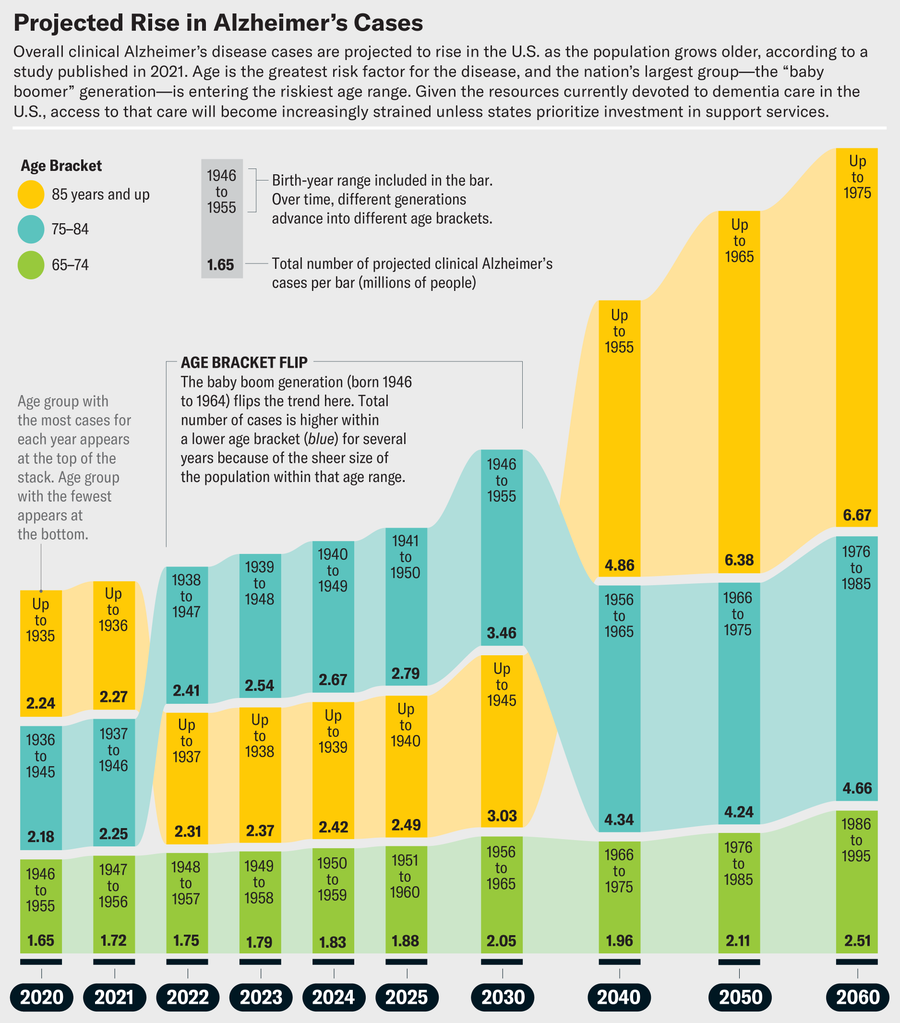

The rate of Alzheimer’s diagnosis has declined steadily in recent decades, but as baby boomers age, the number of new cases continues to rise. The top risk factor for dementia is age, and by 2030 more than one in five Americans will be 65 or older. That means the prevalence of Alzheimer’s in the U.S. could exceed 13.8 million people by 2060.

Jen Christiansen; Source: “Population Estimate of People with Clinical Alzheimer’s Disease and Mild Cognitive Impairment in the United States (2020–2060),” by Kumar B. Rajan et al., in Alzheimer’s & Dementia, Vol. 17; December 2021 (data)

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

If current trends continue, many of them will have no place to go. Save Our Seniors, a collaboration of the American Health Care Association and the National Center for Assisted Living, estimates that more than 770 nursing homes have closed in the U.S. since 2020, and recent federal cuts to Medicare and Medicaid will almost certainly decrease access to long-term care. Older adults overwhelmingly prefer to age in place and receive care at home, but for that to be possible, there must be support for home caregivers, enough people willing to do those jobs, and coordination between local and state services.

A recently launched national resource funded by the National Institute on Aging, the State Alzheimer’s Research Support Center (StARS), aims to help make all that a reality. By gathering data on the effectiveness, accessibility, and equity of state and regional programs for dementia care, then sharing those data, the researchers involved in the project hope to help states build partnerships that will aid policymakers at all levels in identifying the best solutions. Scientific American spoke with Regina Shih, an Emory University epidemiologist and co-principal investigator of StARS, about the problems our aging population is facing and how she and her colleagues are working to solve them.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

As the U.S. population ages, how is the country meeting the needs of people with dementia?

Our long-term-care system is in a crisis. We have done a lot on the health-care side to improve the quality, delivery and accessibility of care. But when you think about assistance with activities of daily living at home—managing medications, transportation, toileting, bathing, getting dressed and making meals—that is the vast majority of dementia spending.

A recent study by a team at the University of Southern California determined that the national cost of dementia is $781 billion a year. Much of that is long-term care and unpaid caregiving provided primarily by family members. And it’s lost earnings because family caregivers have to reduce their work hours or leave the workforce altogether.

What are the biggest challenges in dementia care?

The first is convincing those concerned about cognitive changes to seek dementia screening. Many don’t believe it’s worth getting a diagnosis, because they feel there’s nothing to be done. But you can do lots of things in the early stages of dementia to prevent serious progression [see “Cultivating Resilience”].

There are also challenges in paying for care and in determining who provides it. How do you support family caregivers who are helping someone age in place, and what kinds of providers can help people manage medications and aid with transitions? If there is a hospitalization, how can you prevent long stays, dying in the hospital, or moving someone into a nursing home when they want to age at home? And at the end, it’s about palliative care and a dignified death.

How does StARS aim to solve these challenges?

Our goal is to help states deliver dementia-care programs. We don’t need to reinvent the wheel and create more integrated and coordinated dementia-care programs. There are wonderful models of care we don’t get to hear about because they’re in one institution or within one state. We want to study those models and learn how to increase access to those kinds of dementia-care programs, as well as how to pay for them and meet the needs of different caregivers. That’s what StARS is about—helping state leaders and health-care providers increase the accessibility and affordability of dementia-care programs within their state.

Say your mother has dementia, or you suspect she needs a diagnosis because she’s forgetting how to drive home or can’t remember names of family members. You could talk to your primary-care doctor, but that’s not the only avenue. States are creating innovative programs to help with dementia diagnoses.

The next step is to help states deliver referral services. How does someone with dementia live in their home independently? How do they start preserving their memory? How do they drive independently when they don’t remember the way home? If they can’t prepare food on their own, how do they get meals? How do we get them physical therapy if they’re starting to fall?

We want to help states learn from one another, to say, “State X, do you see how State Y is doing this? It is funding family-caregiver support programs in this way, or it funds meal deliveries in this way, preventing hospitalizations or emergency room visits.”

One example is GUIDE, a coordinated care model being tested by the U.S. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The program assigns a “care navigator” to people with dementia and their caregivers, someone to help them access everything from clinical care to transportation. The goal is to enhance quality of life for people with dementia, to help them stay out of the hospital, receive better care and reduce caregiver burden. The GUIDE sites at the University of California, Los Angeles, and Emory University are among those being tested. There are potentially other innovative models of coordinating dementia care developed within states, and so we want to know whether aspects of those programs work for other states. Are the models serving all communities, rural and urban?

As caregiving needs grow, large numbers of nursing homes are closing. Why?

Costs for nursing home care are high, so CMS is helping states increase access to home- and community-based services, including bathing, physical therapy and end-of-life care. This CMS push has moved care away from nursing homes and means a lot of them have closed their doors. It’s really a crisis to think about where these individuals are going and how much reliance there will be on family caregivers. I have had nursing homes reach out to me and ask, “Who is going to take the residents from our nursing home when we have to close?” The burden of care is going to shift to the public. If someone needs personal care or home care or someone to cook them meals, they have to be either wealthy enough to pay out of pocket or poor enough to be eligible for Medicaid. People who aren’t eligible for Medicaid home- and community-based services often rely on family caregivers.

There are national support programs that can help people learn how to be family caregivers and navigate the care system. For example, I am a volunteer with the Area Agency on Aging (AAA) in Atlanta. Someone can sign up to come to a library or recreation center, and I’ll train them to cope with their stress, to help prevent falls and to navigate behavioral symptoms that come with dementia.

How do family caregivers find out about these programs?

They can go to their local AAA. The name may vary by location; here in Georgia we have Georgia Memory Net. There are clinics across the state where anyone can walk in and say, “Can you help me determine whether my mom has dementia?” Once someone has a diagnosis, Georgia Memory Net provides referrals for services: food access, meal preparation, personal care, home care, physical therapy—all the things they need to stay in their home.

Georgia Memory Net is doing amazing work across the state to help both people with dementia and their caregivers, so other states want to replicate what it’s doing. But do we know whether it results in better outcomes? Does it reduce the burden on caregivers or increase their quality of life? Does it reduce hospital admissions, improve affordability or help family caregivers stay in the workforce? We don’t know, because there’s no data infrastructure to track this information. That’s what StARS is working to build.

One of StARS’s goals is to establish partnerships between new programs and existing successful ones. What would that look like?

States fund things in very different ways, so that’s one way they can learn from one another. There are states saying, “I would like to do something like Georgia Memory Net. How do I do that?” They would look to Georgia, and Georgia would provide them with support. Meanwhile Georgia could look at another state nearby, maybe Tennessee, to see how it has integrated its AAAs and its health-care system or to find out whether a certain type of service referral helps to decrease hospital visits and save money.

What kinds of dementia-care pilot projects are you looking to fund?

We have the health-care system—hospitals and clinics—and we have social service systems like what the AAAs provide, such as meal delivery or bus passes to go to the doctor. Those two systems don’t talk to each other. StARS wants to help states link up their data systems so that an AAA can say, “When I refer people to Meals on Wheels, I think I’m helping them avoid homelessness and hospitalizations, but I’m not sure. When I give them services like this, does that avoid hospitalizations?” The data systems could then be linked together to show that, say, this person ended up in the hospital 60 or 90 days after she received a referral service, or in a year this is the number of hospital visits she had.

We also want to show that linking existing data across different settings of care could help states save money and share best practices with other states. Right now many AAAs have a wait list because the services are in such high demand. There are so many older adults with dementia that some states can’t fully meet the demand for services right now. If StARS could show that referring and coordinating care helps save money by avoiding hospitalizations, for example, maybe states could make the case for more funding for those services. In many AAAs, we have education programs for family caregivers. If we could serve more of them, perhaps they could actually save money by avoiding downstream health-care costs. For example, if caregivers have information on how to reduce falls, the person they’re caring for will be less likely to end up in the hospital. Or the AAA can send services to someone’s home to install grab bars and to secure rugs. Those are things some caregivers can’t afford or don’t know they need.

What would be the ideal societal setup for the growing population of people living with dementia?

I don’t think there is one particular set of services that could meet the needs of every single kind of person living with dementia. I would love to see integrated and coordinated dementia-care programs tailored to meet the needs of all kinds of people with dementia who have different family situations and different levels of access to care. I think there is a lot of promise in saying to states, “We are here to help you figure out what works for specific populations in your state within the ecosystem of care you’ve already built.”

How can StARS help improve dementia care?

One way is to convince state policymakers to increase funding for family-caregiver supports, meal deliveries, home modifications to prevent falls, and other services. Another is to make sure states are aware of innovative ways to deliver those programs. Entities that deliver those services may not have the capacity to share what they do, so StARS wants to centralize those resources. And we could help answer questions such as, “I anticipate an increase in people with dementia in my state. Do I have enough geriatricians and direct-care workers?” Each state needs a financial case to build that pipeline of workers, to create programs and incentives for people to enter those programs.

We want to give states tools that help people with dementia and their caregivers across the full spectrum of care, from diagnosis to everything that follows, and ensure a high quality of life. That includes things such as knowing how to help people with dementia evacuate in a weather-related disaster. It’s ensuring a dignified death and helping the family caregiver with bereavement. We have to help states deliver coordinated programs so that at every stage, no matter where you’re at, the quality of life is the best we can hope for.