The Trump-backed ex-President looks destined for jail.

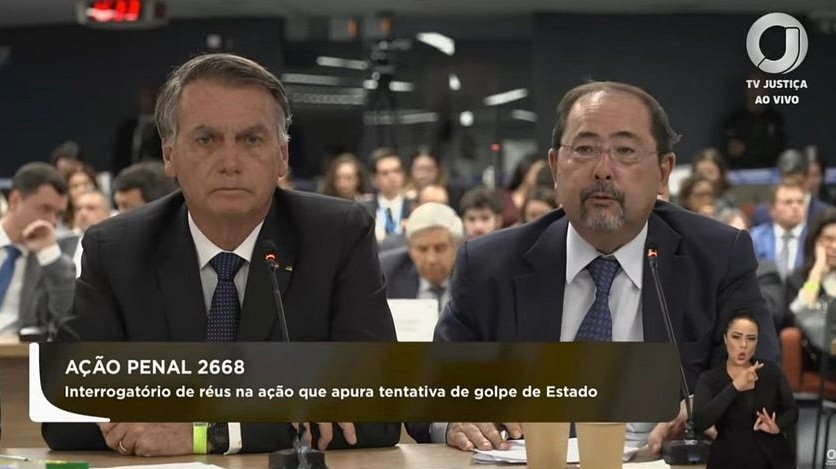

The Jair Bolsonaro who appeared in court was a far cry from the aggressive and crude public persona with which the Brazilian public has become accustomed over the last 40 years. On the stand, he did his best to appear humble and charming. In short, he didn’t threaten to kill any communists,talk about raping anyone, or ridicule people dying of respiratory failure. Nor did he make any spurious corruption allegations against the five members of the Supreme Court’s First Panel, who are ruling on the trial.

During three hours of questioning by Justice Alexandre de Moraes, Justice Luis Fux, and Attorney General Paulo Gonet, he denied that he had ever plotted against the democratic rule of law, downplayed the charges against him, and used every opportunity to promote his four years in the presidency. He took credit for initiatives like the São Francisco River irrigation project—which was 90% completed when he took office—and attributed the drop in the crime rate during his tenure (which corresponds nearly perfectly with the period of quarantine during the COVID-19 pandemic) to his deregulation of handgun ownership.

He threw the January 8 Capitol rioters under the bus, spreading disinformation about their connection to the protest camp calling for a military intervention set up in front of Brasília’s army base. He claimed that, although he insisted the 1964 military coup wasn’t really a coup, he had no idea what Institutional Act 5—which shut down Brazil’s Congress and Senate in 1968—was. “There are the lunatics who cling to this idea of an AI-5, of military intervention by the Armed Forces… but the leaders of the Armed Forces would never go along with it just because people were calling for it.”

When asked why he repeatedly, publicly claimed that the electronic voting system was susceptible to fraud without providing any evidence, instead of answering, he launched into yet another attempt to cast doubt on the electronic voting system. When asked if he had any evidence for his claim, widely dissimenated on social media, that Supreme Court ministers received $30–50 million in bribes, he affected a sheepish grin, said those comments were made in the heat of the moment and apologized, saying, “I don’t have any proof of this whatsoever, Minister.”

When asked if he had shared plans with top military brass about provoking a state of siege so that the army could take over national security and arrest Lula and Supreme Court ministers, he admitted that they had discussed it —claiming he was depressed after losing the election, and that they talked about all kinds of possibilities, but this idea was quickly rejected.

The most surreal moment of his three-hour testimony was when he asked Justice Moraes if he could tell a joke. “If I were you, I would consult with your lawyers on that,” Moraes answered.

“I’d like to invite you to be my vice-presidential running mate in 2026,” he said, as a handful of chuckles rose in the audience.

“Offer declined,” Moraes answered.

This invitation infuriated many of Bolsonaro’s supporters. After all, Bolsonaro’s allies in the international far right have spent the last five years framing Moraes as a Bond-style super-villain.

During two days of testimony from the eight defendants accused of being the “central nucleus” of a two-year attempted coup d’état process—which included plotting to assassinate Lula da Silva, Geraldo Alckmin, and Justice Moraes—polite, self-effacing behavior seemed to be a joint plan. Referring to the fact that most of the defendants were past or current members of the neofascist “Tigradas” faction within the Brazilian military (which never reconciled with the end of the military dictatorship in 1985), legal analyst Arnóbio Rocha said, “The big tigers, Bolsonaro’s troops, became kitty cats in the Supreme Court.”

Immediately after leaving the trial, Bolsonaro abandoned his “kitty cat” routine and aggressively attacked the Supreme Court on social media, tweeting: “Today, I put an end to two absurd narratives that should never have existed. The first is this farce called the ‘coup draft.’ I never discussed any document with coup-related content. I also never participated in or authorized any conversations about arresting authorities. This simply never happened. It’s a baseless lie invented to justify political persecution against me and those who support me.”

However, the vast majority of legal experts quoted in the media disagreed, with most stating that the former president had incriminated himself, further complicating his case.

One example given was his defense strategy of claiming that since they didn’t act on the detailed plan for a military coup—several copies of which were apprehended by the federal police—no crime was committed. The idea that these “preparatory” acts did not constitute a crime was widely criticized, even in the conservative Estado de S. Paulo newspaper, which has a long history of support for the Bolsonaros. It quoted Aury Lopes Jr., a criminal law professor at PUC-PR, explaining that the distinction between preparatory acts and executive acts is central to criminal law. The issue of whether they acted on the coup plot or not is legally relevant, he explained, because planning a coup d’état is a crime in itself in Brazil. “The issue of preparatory acts has already been surpassed,” Crespo said. “The evidence shows there was something beyond that.”

What comes next?

Now that the defendants have finished their testimony, the trial is entering its final stretch. A short period will now be established by the Court for both the prosecutors and the defense to request additional investigative measures based on information gathered during the evidentiary phase of the trial. In Brazil, this generally refers to activities like cross-examining a witness or obtaining documents referenced during the two days of testimony. Presiding Justice Alexandre de Moraes will rule to accept or reject each request. At that point, key witness Lt. Colonel Mauro Cid, Jair Bolsonaro’s former aide-de-camp, will make his final statement. From this moment, the defendants will have a period of 15 days to develop and present their final arguments to the court. At that point, the panel of five justices—Alexandre de Moraes, Carmen Lúcia, Luis Fux, Cristiano Zanin, and Flávio Dino—will issue their ruling, with convictions requiring a majority of three votes.

This first appeared on De-Linking Brazil.