Thousands in southern China have been infected with a mosquito-borne illness in the past few weeks, in what’s considered one of the most notable outbreaks of the disease since it was first detected in the country nearly two decades ago.

The latest outbreak of chikungunya has infected more than 7,000 in the southern Chinese city of Foshan, with sporadic cases in other neighboring cities and municipalities in Guangdong province.

So severe is the outbreak that a vice premier visited a massively affected district in the city last week and “urged efforts to curb imported cases and prevent the spread of Chikungunya both within and outside affected regions,” according to state-run news organization Xinhua. The rapid rise of infections in the province also prompted the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention to issue a travel warning to caution visitors earlier this month.

Read More: Why Mosquitoes Are So Dangerous Right Now

Local officials are now working to combat chikungunya’s spread, using some tried-and-tested epidemic measures to respond to infections as well as more creative efforts, to reduce the population of mosquitoes that cause it.

Here’s what to know about the disease.

What is chikungunya?

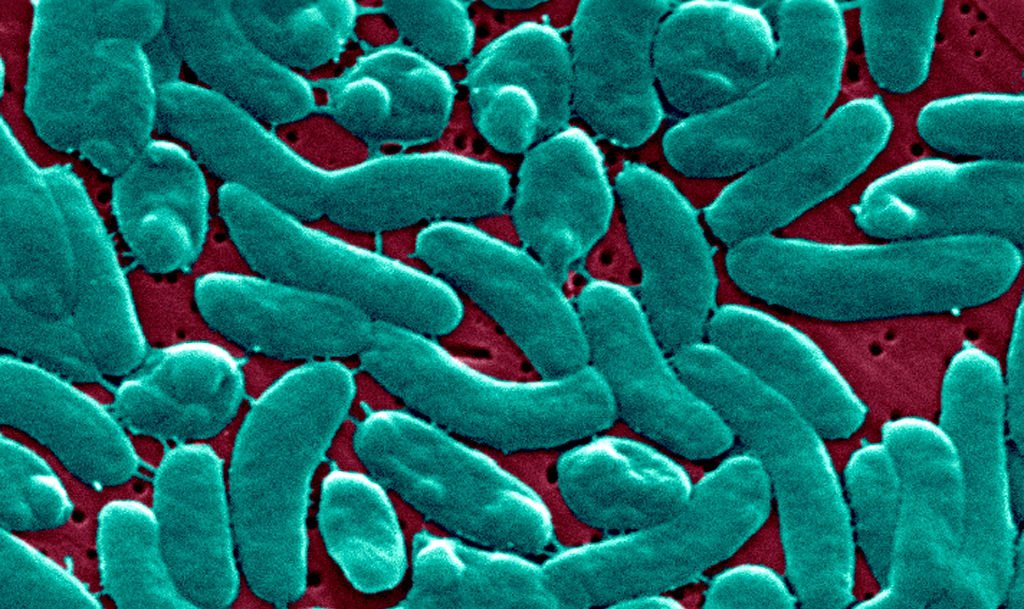

Chikungunya is a disease caused by a virus of the same name. The virus, according to the World Health Organization, is commonly transmitted to humans through the bites of infected female mosquitoes like Aedes aegypti and Aedes albopictus. These species of mosquitoes are also known to carry other disease-causing pathogens, like those that cause dengue and Zika infections.

Symptoms of chikungunya appear, on average, between four-to-eight days after a person is bitten by an infected mosquito. These symptoms may include fever, fatigue, and nausea, but a chikungunya infection is characterized by the accompanying severe joint pain that can last for months or years. The name chikungunya itself is derived from a word in the Kimakonde language of southern Tanzania—where the disease was first identified in 1952—which means “that which bends up” and describes how people infected with it appear stooped because of the associated pain. “People cannot move because it’s so painful. There are tears in their eyes,” Dr. Pilar Ramon-Pardo, a PAHO/World Health Organization adviser in clinical management, told TIME in 2014.

But chikungunya cannot be transmitted between humans and is rarely a fatal disease. A study published in Nature in June estimated that some 35.3 million get infected by the disease across 180 countries and territories per year, but only 3,700 deaths (0.01% of cases). The WHO says infants and the elderly have a higher risk of contracting a severe form of the disease.

There is no cure for chikungunya, and treatment depends on the management of symptoms.

How common are chikungunya outbreaks?

After chikungunya’s emergence in Tanzania, other countries in Africa and Asia also detected the presence of the disease, per the WHO. Urban outbreaks were recorded in Thailand in 1967 and in India in the 1970s.

In 2004, a massive outbreak of chikungunya originated in East Africa, particularly in Kenya’s Lamu Island, where it infected 70% of the island’s population. The disease then spread to other neighboring islands like Mauritius and Seychelles.

India faced a widespread outbreak of the disease in 2006 when it recorded almost 1.3 million suspected chikungunya infections, most of which were from the Karnataka and Maharashtra provinces. That year, there was also a chikungunya outbreak in Sri Lanka, and the following years also saw outbreaks in Southeast Asian countries like Singapore and Thailand, infecting thousands. As of May 4, over 47,500 cases of chikungunya have been reported in the French island territory of La Réunion, and there is “sustained high transmission” across the island since the outbreak began last year, according to the WHO.

In the U.S., the first locally-acquired cases were reported in Florida, Texas, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands in 2014, per the U.S. CDC. By 2015, chikungunya became a “nationally notifiable condition.” The WHO noted in 2016 that “the risk of large-scale outbreaks of Chikungunya virus in the United States is considered to be low,” but indigenous cycles of transmission could not be fully ruled out.

From 2010 to 2019, China had imported cases of chikungunya—including clusters in Dongguan, Guangdong in 2010 and Ruili, Yunnan in 2019—according to China’s National Health Commission.

How bad is the current outbreak in China?

The earliest known symptomatic case in China’s chikungunya outbreak was on June 16, according to the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The latest outbreak’s cases are concentrated in the Shunde District of Foshan, a city of 9 million.

From July 27 to Aug. 2, around 2,892 new local cases of chikungunya were reported, and 95% of the cases were in Foshan. The rest were scattered in other cities and municipalities in the region, including Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Dongguan, and Zhongshan.

On Aug. 4, Hong Kong, the semi-autonomous region and international port China governs, reported its first imported case.

China’s CDC has attributed the 2025 outbreak to imported cases.

“With the virus spreading globally, imported cases have inevitably reached China,” Liu Qiyong, China CDC’s chief expert in vector-borne disease control, told state-affiliated news organization CGTN. “Given the established presence of local transmission vectors, particularly Aedes mosquitoes, these imported infections have fueled sustained local transmission cycles, leading to concentrated, small-scale outbreaks in affected regions.” Chinese authorities have not elaborated on the specific imported case that triggered the outbreak.

Kang Min, director of the institute for prevention and control of infectious diseases at the Guangdong Provincial Center for Disease Control and Prevention, warned that the current flood and typhoon season have also boosted mosquito activity, complicating disease prevention and control efforts.

In response to the outbreak, Chinese authorities are borrowing from their COVID-19 playbook: conducting mass tests, isolating infected residents, and disinfecting entire neighborhoods.

How can one protect themselves from chikungunya?

There is a vaccine against the mosquito-borne illness, but it is not yet available to the public in China. The country’s National Health Commission asserts that preventive measures like “promptly clearing mosquito breeding grounds and reducing the density of mosquito vectors” are the main way to prevent infection. These methods include the mosquito coils, repellents, mosquito nets and other methods to repel, kill and prevent mosquitoes.

In the U.S., the CDC says two vaccines against the disease are available, and it’s advised that those who are traveling to high-risk areas get vaccinated against the disease. Pregnant women should reconsider travel, and should hold off vaccination until after delivery, according to the U.S. CDC.