Rachel Feltman: For Scientific American’s Science Quickly, I’m Rachel Feltman.

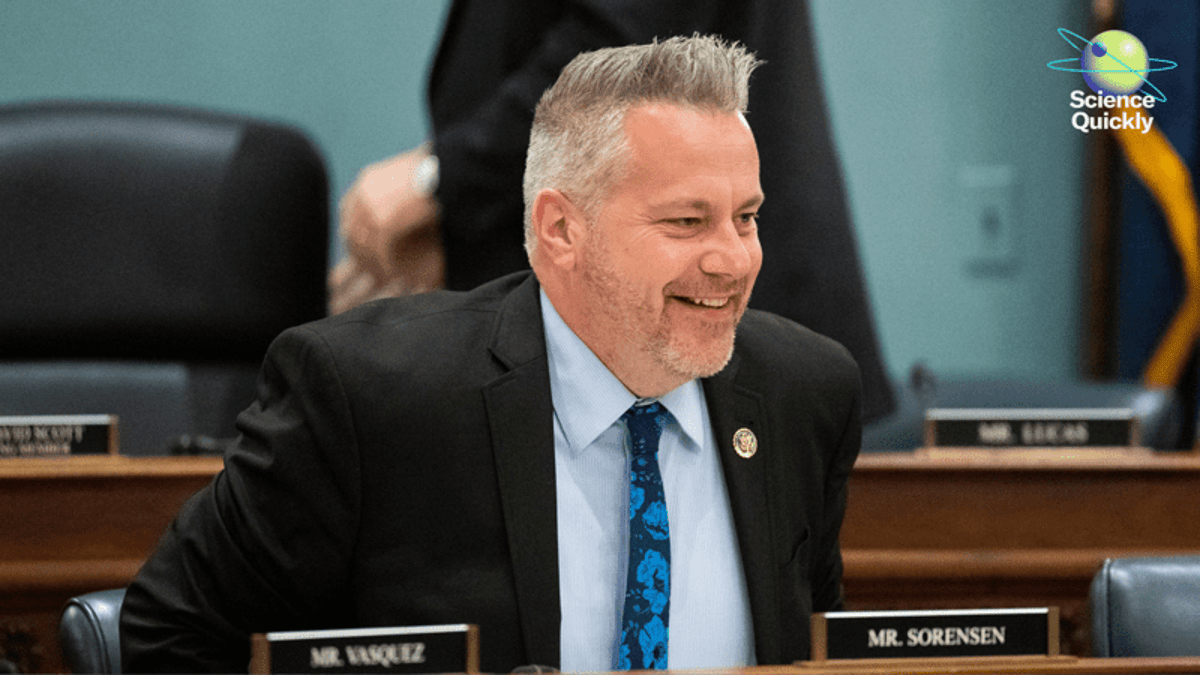

Representative Eric Sorensen of Illinois spent 22 years forecasting the weather on television before winning his congressional seat in 2022. He now finds himself defending scientific agencies from unprecedented attacks at a time when climate change is pushing weather patterns into uncharted territory.

Today we’re talking to Eric about how his scientific background shapes his approach to politics, what he’d change about the country’s approach to catastrophic weather events and why he thinks more scientists should consider running for office.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Thanks so much for coming on to chat with us today.

Eric Sorensen: Oh, it’s great to be with you.

Feltman: I’d love to start with a little bit about your background as a meteorologist. How did you get interested in the field, and what was your career like?

Sorensen: Yeah, I grew up in Rockford, Illinois, and I grew up afraid of storms; I grew up afraid of, of tornadoes, right? And I just had this intense reaction every time they occurred, and I wanted to learn more. I’ll never forget—I thought it was a punishment when my mom and dad took me to the library. They were like, “All right, we need to get Eric to learn more about weather.” [Laughs] Right? And so I’m just, like—as I started learning about it, I was hooked on it as a kid, and so all I wanted to be was the meteorologist on TV, and you know what? I got to do that for 22 years, and it was, like, it was awesome.

Feltman: Yeah, so then what got you into politics?

Sorensen: So, you know, I’ll tell you: a lot of different things. I was somebody who worked in my hometown of Rockford, Illinois, and aside from working in the district that I now serve in the Congress, I worked for a couple of years in Texas, and I am a believer and a lover of science. Everything that I do, I’m, I’m thinking about, “What is a scientific angle?” to whatever we do. And I’m sitting in the weather center, I’m forecasting the weather, at WQAD-TV in the Quad Cities of Illinois and Iowa.

[CLIP: Eric Sorensen delivering a weather forecast on WQAD-TV: “Hi there, everybody, meteorologist Eric Sorensen of the Storm Track 8 Weather Center …”]

Sorensen: And the top story was: our congresswoman Cheri Bustos announced that she was retiring. And the news anchors across the studio from me, they pointed at me, and they’re like, “You need to do that.” I’m like, “I don’t wanna be a politician. That’s stupid. That is the dumbest idea I’ve ever heard,” right?

I honestly was watching the ceiling fan go around, trying to go to sleep that night, and I thought to myself, “Why wouldn’t I do that?” Right?

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: We were going through a pandemic, where we didn’t have enough communicators of science. As we were understanding it, as we were learning it, we needed to communicate it. We only had one Anthony Fauci; we needed 10,000 of him.

Feltman: Yeah.

Sorensen: And so I realized that it wasn’t so much just meteorology but just by being there for people every day and really being trusted, it was the recipe for being elected to Congress. Because I’m gonna tell you, I was a total nerd in school—I would not have been elected the treasurer of my high school class—but the first time I ran for Congress, I won.

Feltman: And how has your background informed how you operate as a politician, and I’m also curious, you know, how has your introduction to politics influenced you as a science communicator?

Sorensen: Well, look, I thought I was just going to go to the Congress and be the communicator of climate.

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: I thought that that’s going to be the lane that I need to travel as a meteorologist, okay? And, and for—in many instances that’s what I do. But then, to be an outsider elected to Congress, it’s a unique perspective, right, because nobody communicates well there at all; we don’t communicate any of the s— that people need to know about.

And so, like, I get there, and I realize, “Oh, wait a minute, Congress has an approval rating of what, like, 20 percent”—something like that—“for good reason,” right? Because nobody there is doing a good job of communicating back home that they’re doing their jobs or that they’re connecting with people or creating these solutions. And then, for me, I will tell you, one of the things that has helped is: I don’t have a background in politics, right?

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: If my background is in science and communicating science, I have to challenge people on the other side of the aisle a lot, but …

Feltman: Sure.

Sorensen: They’re not afraid to work with me, you know …

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: When we need to do some important things.

Feltman: And what have some of your biggest accomplishments been since you were elected?

Sorensen: I’ll tell you, in the first Congress one of the things that—it’s not necessarily related to science—but it was making sure that we passed the All-American Flag Act. It sounds really minuscule, but I’m like, the federal government spends a lot of money on flags, and they should be made in America, by American fibers …

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: And making sure that the grommets are made in America. It is something simple-sounding, but it was really hard to get through the Congress, and people had been trying to do that, and I was able to do that.

Now, I’ll tell you, things have changed in this Congress, you know, as you have President Trump that decides that he’s gonna go after and DOGE go—goes after the National Weather Service and how important these things are and how important the science of understanding climate is. As he goes after it I am the pushback, right?

Feltman: Right.

Sorensen: I’m leading that pushback to make sure that we’re going to stand up for science and stand up for meteorology and climatology.

Feltman: Yeah, well, and I would love to talk a little bit more about that—you know, what, what have you and your colleagues been doing in response to these attacks on the National Weather Service?

Sorensen: I didn’t think that I was gonna have to argue the importance of the weather service, but, you know, I’m so glad that I’m here, right?

And then it was finding members on the other side of the aisle that understand the importance of it. So Congressman …

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: Mike Flood, he’s a Republican out in eastern Nebraska—also, I wanna say, as a meteorologist, I have to work with a guy named Mike Flood [laughs]. I’m just like—I have to.

Feltman: [Laughs] Sure, yeah.

Sorensen: Right? And so he—like, in eastern Nebraska they get a lot of tornadoes …

Feltman: Yeah.

Sorensen: And so we put forth a bill and we’re championing a bill through the Congress that says that National Weather Service employees are essential and that we need to hire them back. And we’re seeing success: we’re seeing that the Trump administration is turning, and now NOAA is able to hire these people back.

I’m working with Congressman Nathaniel Moran. This congressman is in the reddest part of Texas, but also it’s Tyler, Texas—it’s the only place that I worked outside of Illinois—so we have this, like, common bond …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: ’Cause I worked at KLTV. And so it’s: “How are we getting the important weather information to rural America?”

Feltman: Right.

Sorensen: And we started working on that before the tragedy happened in Texas. And so it’s: “How can we make better policy that is not just going to be reactionary when we have these climate-fueled disasters?” It’s: “How are we going to be up front, before they occur?”

Feltman: Yeah, and do you think that your colleagues in Washington in general and the administration specifically, do you think most of them understand the breadth of what the National Weather Service does and how important it is?

Sorensen: The tragedy that occurred in Texas, that’s in Chip Roy’s district …

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: He is one of the most conservative Republican members. So he understands the value of it. He’s not coming out against this now …

Feltman: Right.

Sorsensen: Because it happened to him. Tornado Alley: Oklahoma and Kansas and Texas and Louisiana and Mississippi and Alabama—these are all red states. Or if you look at these hurricane-prone states, much the same: Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Florida—they’re red states, right? So we can’t politicize the science of meteorology.

Feltman: Right …

Sorensen: And I, I would even go even farther than that: to say we should never politicize climatology either.

Feltman: Yeah, and speaking of the politicization of climatology we were just talking on the show recently about the push to pull back the endangerment finding and the report that doesn’t just seem to attack the endangerment finding specifically but does a lot of undermining the basic, accepted science of climate change. What are your thoughts on that? You know, what do you think that Congress and other elected reps can do about that situation?

Sorensen: Well, I think, it’s fascinating to me—the far right, they’re trying to make it more mainstream, that they want people to believe that somehow there’s climate modification going on, or that there’s some sinister—like, airplanes are spraying chemicals into the air and there are all of these nefarious reasons for what you’re seeing, as opposed to understanding the basic climate science that says that humans are causing it but in a different way. Why is it that some people are so susceptible to believing conspiracy theory, yet they won’t believe the actual science?

The science is pretty easy: that we can identify the carbon in the atmosphere to know that carbon occurred because we were burning fossil fuels. We understand these are basic principles of atmospheric science. We know that CO2 is the number one driver of global warming. Yet we don’t do anything about it.

And I will even say, as we are recording this, I’ve got an air-quality alert in …

Feltman: Right.

Sorensen: My part of northwestern Illinois. And we had—forgive me; I use hand gestures when I talk about the weather—we had a cold front come through the area, and now we’re seeing a northerly wind, and that northerly wind is coming off of wildfires in northern Ontario.

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: Let’s understand why this is occurring now versus before …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: Because now we’ve pushed the jet stream so far to the north that the thunderstorms that are producing the cloud-to-ground lightning, okay, they used to happen in the Prairie provinces, right? They used to happen where Canada had fire departments because there’s highways, right? We can go …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: And fight them. But now the jet stream is so far to the north that the cloud-to-ground lightning is hitting in forests that are hundreds of miles away from civilization. And so there’s no way for those to go out.

And as a meteorologist, but also as a congressman, I’m communicating to the people here that what you’re seeing with these air-quality alerts—we had the worst air quality in the world the other day—this is the new norm. This is the new norm …

Feltman: Yeah.

Sorensen: Because we have changed the climate so much, and I don’t know—no one knows—what are the health ramifications for how we’ve changed it? That’s something that we’re gonna know, unfortunately, decades from now.

Feltman: Yeah. What issues are you most concerned about right now when it comes to weather and the climate, and what sort of projects and enterprises are you excited about?

Sorensen: So, look, I worry that we may have people become apathetic …

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: When it comes to the climate crisis. I wish that we would’ve done more. I wish that we had curbed our emissions, that we had done that in the past 10, 20 years, when we understood it, as opposed to just arguing over it. One of my motivations is to be the science guy, the meteorologist that’s not afraid to work in the middle of the aisle to be able to get people to understand that we need to move this forward; we need to make sure that we’re innovating, that we’re sustaining the next generation— also, that it’s smart to do right by the next generation.

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: Let’s talk about those things. So I do worry that as I am finding movement to move forward in the center of the aisle—even in a Trump administration it is occurring, right …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: I worry that as I move people forward we’re gonna lose the people that are maybe to the left that will say, “It’s too late of a cause. Why did I try so much?” And so we do need to make sure that we don’t give up on this. It’s not worth …

Feltman: Yep.

Sorensen: Giving up, and we can’t do it.

Feltman: Yeah, absolutely. And what are you feeling optimistic about right now?

Sorensen: I’m really excited because I’ve been working kind of day in, day out right now—after the tragedy that we saw on the Guadalupe River in Texas, when I started seeing politicians just pointing fingers at each other and I’m like, “That’s not gonna solve a problem.” Or: Do we argue how fast FEMA is going to get there afterwards? Why aren’t we looking at what happened before?

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: In the same respect, when we have an air disaster in this country, we have the [National Transportation Safety Board]. The NTSB goes and looks through every piece of data before the disaster occurred, everything that led up to it, so that we can change the policy, that we can change design.

I looked back: 1985, there was a horrific plane crash in North Texas—it was Delta 191. That hit wind shear, it hit a microburst from a storm, and it crashed and killed a lot of people. I was nine years old. It was the first thing that I really thought about when I was like, “Oh, meteorology played a role here.”

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: But we don’t have this type of air disaster happening because we implemented Doppler radar at the biggest airports in the country now, so we can identify it so that airplanes don’t go into it. But that finding needs to happen every time there’s a weather disaster. And so I’m proposing an NWSB of sorts. Why can’t we go back and look, before the tragedy occurred, every piece that went wrong? ’Cause I think you’re probably gonna realize that it isn’t necessarily [going to be] in our lack of understanding of science. It’s gonna be in social science. It’s going to be …

Feltman: Mm-hmm.

Sorensen: “How do people perceive risk? Do people understand what is at stake? Do people understand that every time your phone goes off, it isn’t gonna kill you, but you need to pay attention for that one time where there is something that could?” And then develop the policy that’s gonna save people in the future. And I’m like, that’s a pretty good legacy to have, if we could do that in a bipartisan way.

Feltman: Yeah, absolutely. Is there anything we haven’t touched on that you think is important for us to talk about before I let you go?

Sorensen: A lot of people, they said, “There’s no way that a meteorologist could be elected to Congress.” And one of the things that I wanna be able to say is—it was really hard to blaze a trail through the jungle, right? I feel like I was trying to chop down all of these branches [laughs] to, to fight to find this path. And I wanna be able to look back on this path and see the next person coming up. I wanna be able to see other people say, “I wanna take part in this; I feel like I can make a difference,” and that, actually, science is one of those things that can bring us together when politics wants to break us apart.

And so my hope is, even though I’m just one meteorologist in Congress, that it will inspire other people and other people in science to say, “You know what? We do need to communicate these other things, too.” Or maybe if there’s a meteorologist somewhere out there that has worked in television for 25 years, earning the trust, that they’re gonna start to think, “Wait a minute, I might be that person.”

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: Or if it’s somebody listening to this podcast that says, “Oh my gosh, I really trust this person. They have really helped me. Maybe I need to reach out to them and say, ‘Did you know there’s a meteorologist in Congress? I want you …’”

Feltman: Mm.

Sorensen: “‘To do this because you’ve helped me.’” That’s what public service has to be about.

Feltman: Well, thank you so much for coming on to chat with us today. I really appreciate it.

Sorensen: Oh, it was great, and I hope to be on again in the future, if you’ll have me.

Feltman: Absolutely.

That’s all for today’s episode. We’ll be back on Monday with our weekly science news roundup.

Science Quickly is produced by me, Rachel Feltman, along with Fonda Mwangi, Kelso Harper and Jeff DelViscio. This episode was edited by Alex Sugiura. Shayna Posses and Aaron Shattuck fact-check our show. Our theme music was composed by Dominic Smith. Subscribe to Scientific American for more up-to-date and in-depth science news.

For Scientific American, this is Rachel Feltman. Have a great weekend!