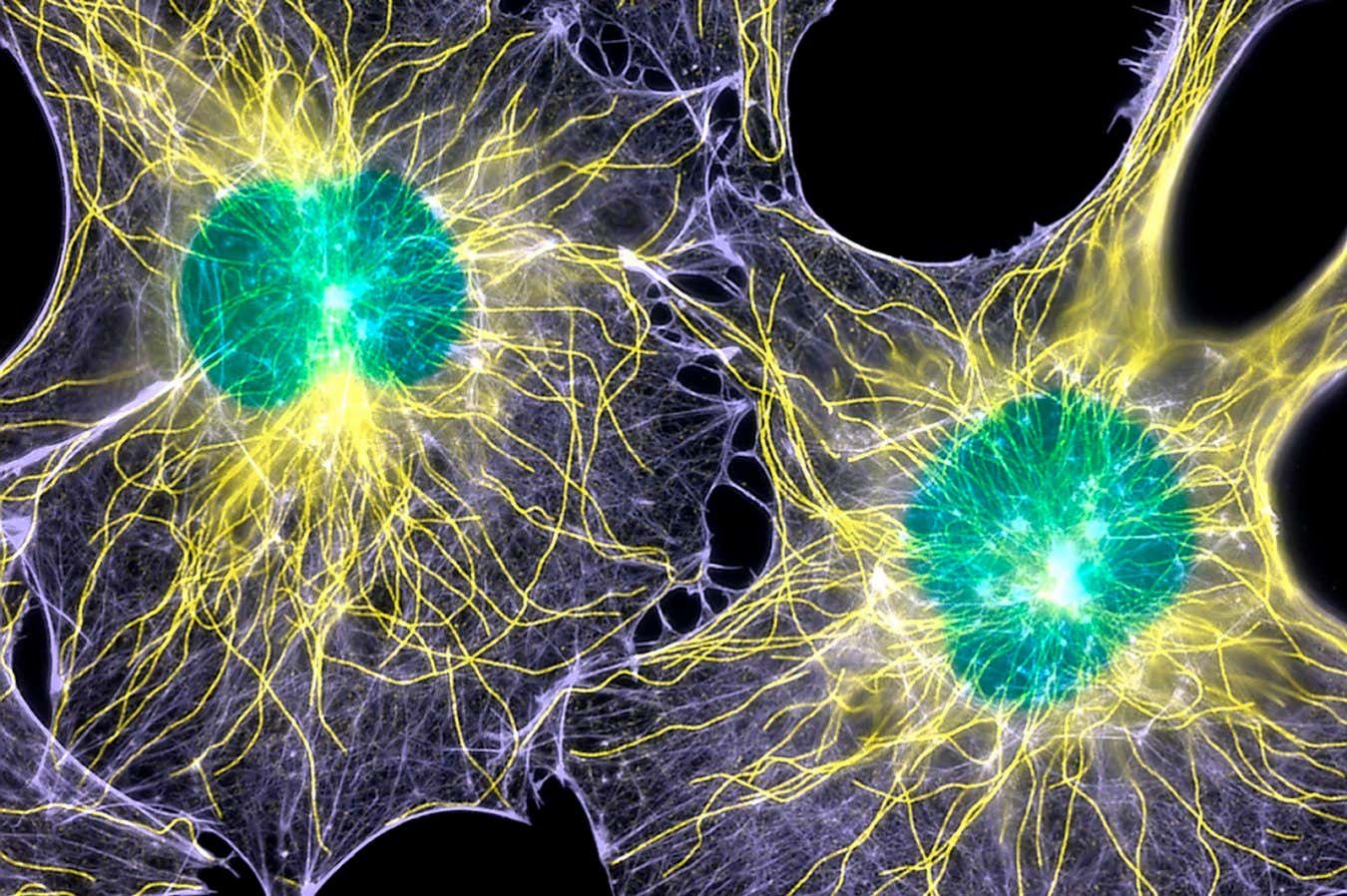

Fibroblast cells, which contribute to the formation of connective tissue but are also involved in scarring

DR TORSTEN WITTMANN/SCIENCE PHOTO LIBRARY

New insight into how mouth wounds heal without scars could pave the way for treatments that prevent permanent blemishes or disfiguration of the skin.

“There’s millions of people who suffer from scars from so many things – injuries, surgeries, burns,” says Ophir Klein at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles, California. “It’s a huge burden not just in terms of cosmetics, but in terms of function,” he says. For instance, a large scar may tighten the skin on your leg, hindering movement, he says.

To address this, Klein and his colleagues made use of the fact that wounds inside the mouth heal without scarring. “If you bite the inside of your mouth, not only does it heal more quickly than the skin, but it heals better in terms of not having a scar,” he says.

Looking into why this is the case, the researchers created 2.5-millimetre-wide wounds inside the mouths and on the faces of mice. They then collected tissue samples from the wounds as they healed over the following week.

The team examined cells involved in scarring called fibroblasts, and found that those in the mouth had greater activity in genes that encode proteins called GAS6 and AXL compared with fibroblasts in the skin. These two proteins are known to interact to enhance cell growth, migration and survival.

The GAS6-AXL pathway seemed to suppress levels of a protein called FAK, which deposits proteins in wounds to form scars. We knew the pathway existed, but we didn’t know it was involved in scarless wound healing, says Klein.

Next, the researchers wondered whether boosting the GAS6-AXL pathway could reduce skin scarring, so they applied a solution containing GAS6 to freshly formed facial wounds on mice. Two weeks later, these wounds had lower FAK levels and less scarring compared with identical wounds in untreated mice. “They nicely demonstrated that boosting this pathway could reduce scars,” says Jason Wong at the University of Manchester in the UK.

“It’s definitely a stepping stone to what could be a scar-free world,” says Ines Sequeira at Queen Mary University of London. But there are differences between the skin of mice and people, so further work should test the approach in larger animals such as pigs, which have skin that is more similar to our own, before human trials are carried out, she says.

Topics: