India is the first among developing countries to host the AI Impact Summit. Official messaging emphasizes the summit as an opportunity to “give voice to the Global South” and democratize artificial-intelligence resources for all.

The “Global South” represents a diverse group of countries — and India isn’t the only one vying for leadership, investments, and a seat at the table. While India has been positioning itself as being data-rich and the AI use case capital of the world, other countries like Rwanda and Nigeria have positioned themselves as sites for scaling hubs, and the United Arab Emirates is increasingly attractive for Big Tech to raise the capital it needs to finance AI infrastructure build-out. Elsewhere, we have seen massive AI for social good or AI for development plays.

The upshot is the same: Low and middle-income countries are advertising their populations as a path to scale for AI companies. By offering their wide base of customers and data to corporations, these countries hope to demonstrate they are investment-worthy. They also offer the feel-good narrative of using AI to improve the lives of impoverished populations.

The prevailing sentiment is that failure to become active users and innovators of AI will result in further marginalization. At the same time, there is an almost utopian belief that AI can resolve long-standing structural problems, from poverty to climate crisis.

However, the promise of AI for good or AI for development closely resembles earlier development narratives: It obscures trade-offs, externalities, and power asymmetries. There is little transparency around who bears the costs, who captures the value, and whose priorities ultimately shape these technological pathways. Labor in low and middle-income countries powers AI via content moderation, data labeling, and even humans masquerading as AI. These countries have critical minerals used throughout the AI supply chain. Land, energy, and water in already resource-strapped countries are increasingly being used for data centers. Unequal dynamics are structuring not only relations between developing and developed nations, but also elsewhere, with India actively exporting software platforms and services.

As we look ahead to the Summit, we need to scrutinize agendas that read like sales pitches for government adoption of AI, especially with AI-for-government strategies from OpenAI, Google, and others. For example, will the spotlight on “linguistic diversity” be in service of making dominant large language model products accessible and legible to more populations — or is there support for genuinely localized alternatives?

The prevailing sentiment is that failure to become active users and innovators of AI will result in further marginalization.”

India has positioned itself as a “third way,” an alternative to U.S. and Chinese approaches that mobilizes the promise of using technology to benefit not corporations or the state, but the public. This people-centered framing is one that many civil society and philanthropic actors champion as being necessary to reclaim AI sovereignty from exclusively industry or geopolitical imperatives.

India’s approach is best captured in its global push for digital public infrastructure, or DPI — a buzzy shorthand for a state-backed technology stack modeled on India’s digital identity program, Aadhaar; its unified payments interface; and data exchange systems. DPI promises a template for building scalable, context-specific, and cost-effective tech solutions, particularly for developing countries seeking alternatives to Big Tech-dominated systems. DPI is being linked to AI as well, though it is still unclear what this means in practice.

DPI promoters use narrow technical precepts to make claims about openness, which is imagined as automatically benefiting the public. In practice, many of these applications have been experienced as closed, inscrutable systems that enable surveillance and facilitate private capture of public functions at an enormous human cost. The use of algorithmic decision-making to mediate access to welfare, for example, has locked people out of benefits and other critical services with little accountability. And despite messaging around challenging Big Tech hegemony, India’s open protocol for payments is dominated by Google Pay and Walmart-owned PhonePe. This tension is further compounded by the volatility of U.S.-India relations, and the need to contend with China’s role in global AI governance.

Similar debates around “openwashing” are very much alive in the AI context, where flimsy definitions function to obscure the infrastructural dependencies that run through the AI stack..

Can this summit genuinely be a moment for challenging how power is distributed globally in the AI economy?”

Another undercurrent is that governance is no longer really the government’s problem. It instead swings between a techno-legal approach, where code is law, and voluntary self-regulation, where rules are not enforceable. India’s recently released AI Governance Guidelines ask regulators to “support innovation while mitigating real harms; avoid compliance-heavy regimes; promote techno-legal approaches; ensure frameworks are flexible and subject to periodic review.” These recommendations suggest an effort to keep AI governance depoliticized, adaptable, and innovation-friendly, reflecting a broader emphasis on maintaining India’s global competitiveness.

The summit track on democratization of AI could lead with a challenge to the current concentration of compute and data resources in the hands of a few Big Tech firms, but could just as easily sidestep questions of power distribution in favor of a more benign mandate of access to more compute. India’s use case capital positioning fits well with this posture, allowing the country to focus on a burgeoning downstream AI startup ecosystem while sidestepping a key question of value distribution and Big Tech power: Will these startups be more than barnacles on the hull of Big Tech companies that still control the underlying computing and foundation model infrastructure?

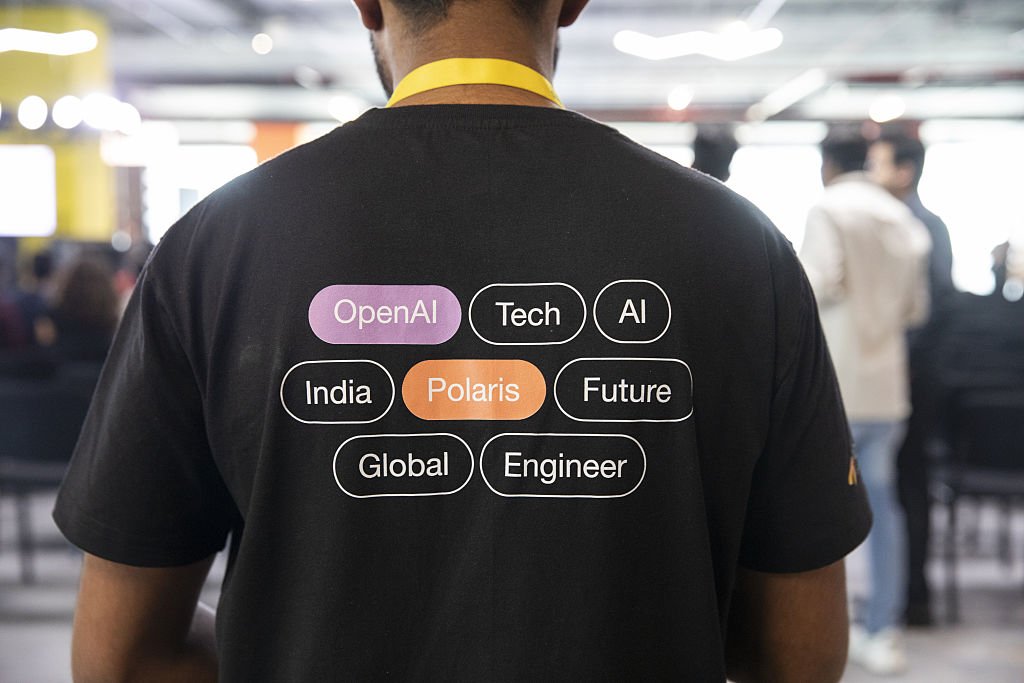

India is open for Big Tech business — despite its public emphasis on homegrown products. The country’s OpenAI Learning Accelerator emphasizes expanding access to AI for educators; Anthropic’s India strategy is focused on adoption of AI in agriculture, education, and Indian languages; Google is pushing DPI and AI integration in health care, and using India as a resource for model testing and improvement. Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon have made similar announcements on cloud infrastructure, skilling, and application layer growth. These effectively make India a site for localizing existing models and scale, but not a locus of control or leadership.

In courting U.S. tech capital, India’s own aspirations of digital sovereignty do not find utterance in the summit’s documentation, even as Big Tech itself has cashed in, offering sovereignty-as-a-service to governments. As we’ve learned, in the tussle between states and Big Tech, it is always regional, community-oriented, bottom-up notions of sovereignty that lose out.

There is wide-ranging global consensus that the unprecedented levels of power in the AI industry are a key challenge of our time — from governments increasingly anxious about their core digital infrastructure being beholden to the whims of foreign tech CEOs and to a general public that is grappling with the growing harms of the AI boom.

In this context, the India summit, with its impact-oriented framing and calls to internationalism and “leadership of the Global South,” offers fertile terrain to build resistance to the status quo, and to stitch together the burgeoning national and local efforts that collectively represent a people-centered alternative. Can this summit genuinely be a moment for challenging how power is distributed globally in the AI economy?