CNA Staff, Aug 6, 2025 /

11:14 am

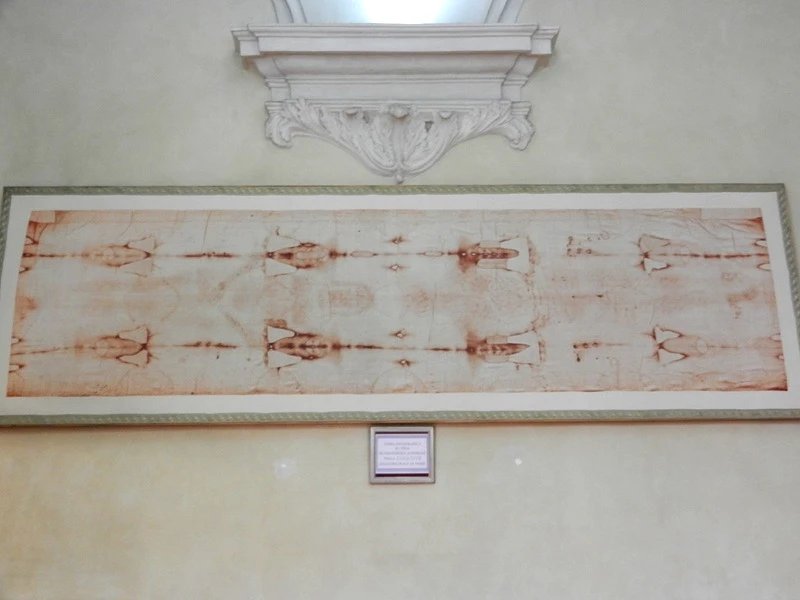

Few religious artifacts have been studied and debated as extensively as the Shroud of Turin.

Countless Catholics and other Christians across the world believe it is the authentic burial cloth of Jesus Christ, wrapped around his body after his crucifixion and marked by his unmistakable visage and form.

Critics, meanwhile, have for years alleged that it is nothing more than a forgery — a clever work of religious art and an impressive technical feat that carries no more or less religious significance than a painting or statue.

Those claims were made most recently by Cicero Moraes, a Brazilian 3D artist who in the scholarly journal Archaeometry last month claimed that the depiction of Christ’s body on the shroud was likely made by a “low-relief model” such as a statue rather than a human body.

The imagery on the shroud is “more consistent with an artistic low-relief representation than with the direct imprint of a real human body, supporting hypotheses of its origin as a medieval work of art,” the study alleges.

The Brazil study has generated widespread coverage in the media, with mainstream outlets such as the New York Post and the New York Sun reporting on the study’s findings. Internet outlets such as Gizmodo and Live Science also touted the conclusions of the study.

Studies point to first-century shroud of torture victim

Moraes’ study has already been criticized for its methodology. The International Center of Sindonology — the Turin-based organization that leads studies of the shroud and promotes its status as a venerated object of Christian devotion — said the findings of the study were disputed more than 100 years ago.

“There is nothing new in this conclusion of the article,” the center said on Aug. 4.

The Vatican has never officially pronounced on the shroud’s authenticity, though popes have held it up as an object of veneration.

Pope Francis in 2015 said the cloth “attracts [us] toward the martyred face and body of Jesus,” while in 2010 Pope Benedict XVI said its depiction of Christ points to the days that the Lord’s body rested in his tomb, a time “infinite in its value and significance.”

Extensive secular studies, meanwhile, have suggested the shroud is authentic at least as a first-century object that came into contact with the body of an executed man.

In 2024 a study from an Italian researcher that analyzed the blood on the shroud argued that the stains are consistent with the torture and crucifixion of Jesus Christ as described in the Gospels.

University of Padua mechanical and thermal measurement professor Giulio Fanti said the bloodstains on the side and the front of the shroud show blood flowing in three different directions, indicating the likelihood that the corpse was moved at some point when wrapped in the shroud.

The three distinct colors of blood on the shroud, meanwhile, suggest three “different types of blood,” which are “postmortem blood leakage” from moving the body, “premortem bloodstains” that likely occurred “when Jesus was still nailed to the cross,” and “leaks of blood serum.”

Fanti’s study indicated that the stains appear to show scourge marks consistent with the scourging at the pillar and that the quantity of blood matches the amount of blood that would have resulted from the wounds described in the Gospels.

(Story continues below)

Subscribe to our daily newsletter

Nanoparticles in the blood samples on the shroud, meanwhile, were marked with the organic substance known as creatinine, indicating “very heavy torture” suffered by whomever the shroud enveloped.

Complex shroud image must be accounted for

Cheryl White, a professor of history at Louisiana State University Shreveport and author of the upcoming book “The Shroud in the Third Millennium: Confronting the Limits of Human Knowledge,” disputed Moraes’ historical research and his scientific methodology.

In his study, Moraes indicates that there is no historical evidence for the shroud prior to the 14th century, but White pointed out that some scholars have argued for the shroud’s appearance in the historical record even hundreds of years before that.

“That’s the type of historical reductionism that I don’t think has any place in serious scholarship,” she said. “You can’t selectively choose the historical data you want.”

Beyond that, she argued, while Moraes places “very heavy emphasis” on the technical aspects of the 3D model he used, he “doesn’t really engage with the complexity of the image” on the shroud itself.

“There’s an information transfer that takes place in the image formation that directly embeds a body-image in the top microfibers of that linen,” she said. “It’s a direct distance-to-body spatial mapping that’s in there.”

Moraes’ study “does not account for complexity in that image,” she said. “It’s a 3D relief in that image. If you haven’t explained that, you haven’t explained the image.”

Others have argued that the imagery would have been beyond the capabilities of medieval artists. Father Robert Spitzer, a Jesuit priest and president of the Magis Center of Reason and Faith, told CNA last year that a medieval forger would be unlikely to have anticipated the highly technical inquiries to which the shroud would be subject in the 21st century.

A forger “certainly would not have used the hematic serum of a victim who experienced a heavy polytrauma,” he said.

Critics have also argued that scientific tests have proven that the shroud dates from the medieval period. Radiocarbon experiments in 1988 suggested that the cloth dates to Europe sometime after the 12th century rather than the first-century Middle East.

Yet other studies have pointed to much older dates, including a 2022 X-ray study at the Italian Institute of Crystallography, which suggested the cloth was around 2,000 years old.

Liberato De Caro of the Italian National Research Council told the National Catholic Register, CNA’s sister news partner, that radiocarbon studies can produce errors in dating.

“About half the volume of a natural fiber yarn is empty space, interstitial space, filled with air or something else, between the fibers that compose it,” he said.

“Anything that gets in between the fibers must be carefully removed. If the cleaning procedure of the sample is not thoroughly performed, carbon-14 dating is not reliable.”

De Caro’s team developed “a method to measure the natural aging of flax cellulose using X-rays and then convert it into time elapsed since fabrication,” he said.

That methodology, he said, “show[s] that the sample of the Shroud of Turin … should be much older than the approximately seven centuries indicated by the radio-dating carried out in 1988.”

Other studies have shown similarly compelling evidence of the shroud’s ancient provenance, including examinations of pollen grains that indicate the cloth came from the Middle East, not Europe.

Still other arguments have turned on the stunning level of detail in the shroud’s depiction, including blood flows and depictions of wounds that would seem to be beyond the abilities of medieval painters.

Disputes about the shroud will surely continue, particularly in light of the Holy See’s continued ambivalence on its true authenticity, even as many reliable sources point toward its first-century origins.

What is also doubtlessly true is that the cloth will continue to serve as an object of devotion and focus for Christians around the world — allowing man, as St. John Paul II said, to “free himself from the superficiality of the selfishness with which he frequently treats love and sin.”

“Echoing the word of God and centuries of Christian consciousness, the shroud whispers: Believe in God’s love, the greatest treasure given to humanity, and flee from sin, the greatest misfortune in history,” he said.