Costa Rica marks 204 years of independence today, September 15, with parades and lanterns lighting up the night. For expats and visitors settling into the pura vida lifestyle, it’s a good time to glance at the past. What did daily life look like in this corner of Central America before the break from Spain? The area, then a backwater province, dealt with tough terrain, small populations, and a rigid social order that set the stage for the country we know now.

Back in the 1500s, Spanish explorers claimed the land, but Costa Rica never ranked high on the empire’s list. Unlike Mexico or Peru, it lacked gold or silver mines to draw crowds or cash. The territory fell under the Kingdom of Guatemala, a loose setup covering much of Central America.

Borders worked one way on the Pacific side, but the Caribbean and southern edges stayed fuzzy, blending into neighboring areas. By the late 1500s, the province stretched from the Tilarán mountains in the north down to Bocas del Toro in what’s now Panama. The Nicoya region ran as its own district, handling local matters somewhat apart from the main action.

Life stayed quiet for centuries. The 17th and 18th centuries painted Costa Rica as one of Spain’s poorest outposts. Mountain ranges, dense forests, and few roads kept it cut off from bigger colonial hubs like Guatemala City or Mexico. Trade routes barely touched it, so folks scraped by on farming and herding. Cartago, the main town since the 1500s, acted as the political center.

A small group of Spanish-born elites and local Creoles—people of Spanish descent born in the Americas—called the shots there. They owned big haciendas, raising cattle and renting plots to poorer farmers, including mestizos, mulattos, and zambos (mixed Indigenous and African heritage).

Pinpointing the population proves tricky, thanks to spotty records. Historian Bernardo Augusto Thiel dug into church books in 1901 and figured around 52,600 people lived in the province by 1801, counting Nicoya. Of those, about 4,900 were full Spaniards, 8,200 Indigenous, and over 30,000 mestizos or ladinos—a term for mixed folks who adopted Spanish ways.

Another 9,000 fell into categories like mulattos, sambos, or pardos, with a few thousand enslaved Africans or their descendants mostly in the Caribbean lowlands. Most everyone clustered in the Central Valley, where the soil suited crops like corn and beans. Indigenous groups held on in spots like Cot and Quircot near Cartago, keeping some traditions alive despite pressures to convert or move.

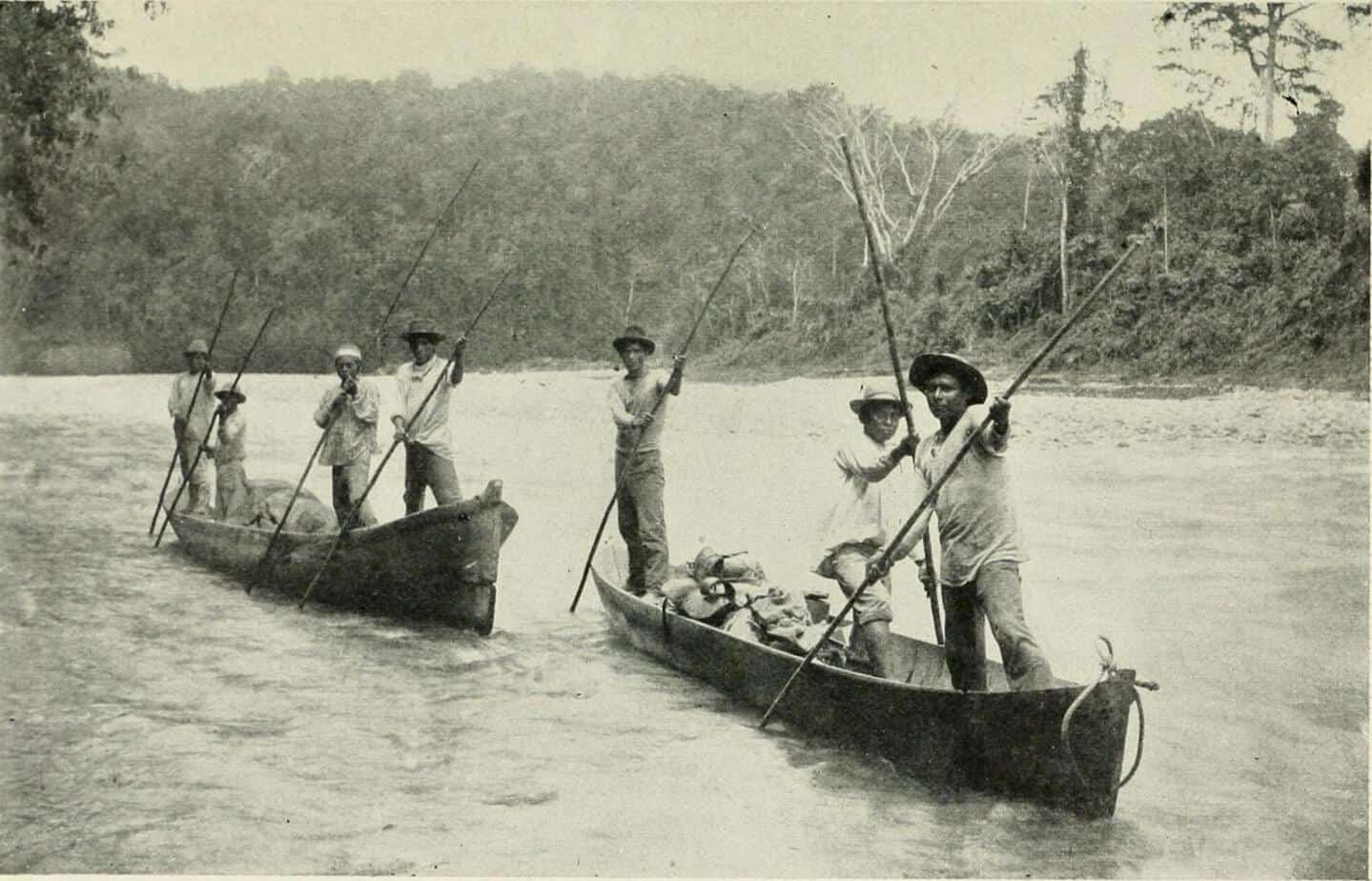

The Caribbean side told a different story. Matina, a key area for cocoa plantations, drew enslaved workers from Africa in the 1700s. Owners from Cartago shipped the beans out but rarely set foot there themselves. Guanacaste, up north, saw Indigenous Chorotega and others pushed out early—some relocated to Bolivia by the Spanish in the 1500s. African-descended communities filled the gap, shaping towns like Nicoya, Santa Cruz, and Liberia with their labor and customs.

Things started shifting in the 1700s with Spain’s Bourbon Reforms. The crown pushed for tighter control and more taxes, which meant building roads and founding new settlements. San José popped up in 1737, Heredia in 1763, and Alajuela in 1782—often by moving people from older spots like Cartago.

These towns turned the Central Valley into a busier place. Tobacco became a big deal after Spain gave Costa Rica a monopoly on growing it for the empire. Farmers and traders cashed in, and some branched into shipping goods to Panama or even South America.

David Díaz, a historian at the University of Costa Rica, points out how San José and Alajuela started pulling ahead of Cartago. “They became centers of economic power,” he says. Figures like merchant José Rafael Mora Porras and Gregorio José Ramírez rode this wave, linking local goods to wider markets. By the early 1800s, the province hummed with more trade, though inequality stuck around. The elite kept their grip on land and decisions, while peasants and mixed-race workers toiled on the edges.

Indigenous life varied by region. In the valleys, groups like the Huetar faced land grabs for farms and missions. Spanish priests built churches and schools, but many natives held onto languages and farming methods. On the coasts, isolation helped preserve some autonomy—Talamanque groups in the south traded with ships but dodged full control. Women, mostly from lower classes, handled home duties and small trades, with few records of their roles beyond family ties.

By 1821, winds of change blew from Mexico. When that country declared independence, the news rippled south. On September 15, leaders in Guatemala City signed the Act of Independence for Central America, including Costa Rica. It took almost a month to reach Cartago—October 13—since no fast messengers existed. Folks there debated joining Mexico’s empire or going their own way, but the shift marked the end of direct Spanish rule.

This pre-independence era left lasting marks. The Central Valley’s farms fed a growing population, setting up coffee’s later boom. Ethnic mixes from Spanish, Indigenous, and African roots built the diverse society expats see today. Social gaps lingered, but the push for local control planted seeds for Costa Rica’s stable path ahead—unlike bloodier breaks elsewhere in Latin America.

For tourists or expats wandering San José’s markets or Guanacaste’s beaches, these old stories add layers. Next time you are drinking coffee (hopefully brewed with a chorreador), in the valley or spot a cocoa pod, think of the hands that shaped it all before the flags flew free.