“I want to get a nice big old stir fry and some kiwi fruit juice. That’s what I want,” said Bryan Hooper Sr., minutes after walking out of Stillwater Prison into the arms of his daughter Briana and son Bryan Jr., who grew up without their father while he was incarcerated for 27 years.

Hooper was released late Thursday morning on the order of Hennepin County Judge Marta Chou, who vacated his first-degree murder conviction for the 1998 killing of Ann Prazniak in Minneapolis after a woman serving a prison sentence in Georgia in an unrelated case confessed to the crime.

Prazniak, 77, lived alone in a third-floor apartment near downtown Minneapolis. In April of 1998, police found her body stuffed into a box in a bedroom closet. The Hennepin County Medical Examiner said that Prazniak had likely been dead for several weeks.

After the murder, people used Prazniak’s Park Avenue home as a drug den. Despite a lack of physical evidence, police pinned the murder on Bryan Hooper Sr., who was 27 at the time and admitted entering the apartment.

Based on testimony from jailhouse informants and Chalaka Young, who was also in the apartment, a jury convicted Hooper and a judge sentenced him to life in prison with the possibility of parole after 30 years.

In July, Young, who was known in 1998 Chalaka Lewis, not only recanted her trial testimony, but also she also admitted killing Prazniak and lying on the witness stand to implicate Hooper. Even though four jailhouse informants also recanted, Hooper told reporters outside Stillwater Prison that it was Young’s confession that finally set him free.

“I’m so glad that she did the right thing, and God bless her,” Hooper said

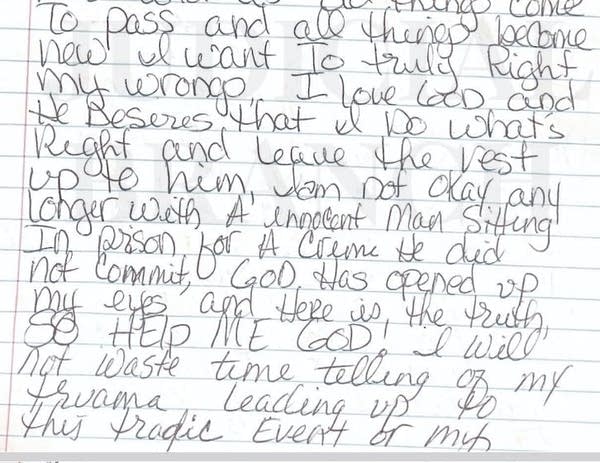

In a seven-page handwritten statement Young writes “I am not okay any longer with an innocent man sitting in prison for a crime he did not commit. God has opened up my eyes and here is the truth.”

Attorney Jeff Dean, who represented Hooper at his trial, is not accusing prosecutors of misconduct, but he said police had “tunnel vision” and refused to look at evidence that pointed to Young as the killer.

“Her fingerprints were on the murder weapon,” Dean said. “They did not even analyze that until after they charged Bryan Hooper. At that point they were stuck with him being the one who was charged. And I believe that the police mishandled this case completely.”

In 1998, Young testified falsely that Hooper forced her to stand watch as he killed Prazniak, who died of asphyxiation. Court records show that investigators found Hooper’s fingerprints on two baggies and a beer can in the apartment, but not on the packing tape that Young used to wrap up Prazniak’s body.

Jim Mayer, a lawyer with the Great North Innocence Project, worked on the case along with the Conviction Integrity Unit that Hennepin County Attorney Mary Moriarty set up last year.

Mayer said getting judges to hear the exonerating evidence was difficult because the jailhouse informants all recanted at different times, and Minnesota has a strict two-year limit on when defendants can bring new evidence to court.

“You have to come into court quickly because you lose your right to bring that new evidence,” Mayer said. “But when you bring it in and the court says that’s not good enough, you need more, and then you come back into court years later with something more, now we can’t use the old thing because that’s already been talked about. That’s in the past. What have you got that’s new?”

Mayer said that Young’s confession was hard for the court to ignore because it was unprompted and genuine. He says without the confession, he’s unsure what recourse Hooper would have had.

Prosecutors have yet to charge Young with Prazniak’s murder. Young has about four years left on her assault sentence in Georgia.

When he left Stillwater, Hooper — now 54 — thanked his attorneys and his children Bryan Jr. and Briana for sticking by him for half his life.

“They made my time much easier knowing they were doing good. That’s what kept me grounded.”

Hooper also called on prosecutors to end their use of jailhouse informants so others like him aren’t wrongfully convicted.