Dave Setterholm steered his motorboat across Farm Lake then cut the engine along the Kawishiwi River near the edge of the Boundary Waters wilderness.

Cross into the Boundary Waters and Setterholm said he’d still dip a cup over the side of a canoe to drink the pure water. But eating fish out of these lakes is another matter. There’s mercury in the water. Anglers are warned against eating more than one fish a month.

“And for my grandson, who was just here the other day, he shouldn’t eat anything until he’s at least 15. Or if you’re thinking about being pregnant, you shouldn't be eating it,” said Setterholm, who directs water quality testing for the White Iron Chain of Lakes Association.

“To me, that’s scary.”

Pollution doesn’t respect boundaries. Hundreds of lakes across the North Woods are contaminated with mercury, including those in protected areas like the Boundary Waters. That contamination is worsening now despite years of efforts to close coal-fired power plants and scrub industrial emissions.

Minnesota has reduced the amount of mercury it spews into the atmosphere by nearly two-thirds since 2005. Yet the level of mercury found in walleye and northern pike in many of the state’s lakes has continued to slowly but steadily rise for the past 30 years.

In the Boundary Waters, more than 100 lakes are considered impaired because of mercury levels that lead to limits on fish consumption.

In Basswood Lake near Ely, 80 percent of walleye and northern pike sampled were over the mercury threshold considered safe to eat. Farther west in Crane Lake near Voyageurs National Park, fish sampled recently had levels 3 to 7 times that threshold.

Scientists cite a web of complex factors contributing to the rise of mercury in fish in Minnesota lakes, including climate change, invasive species and sulfate, a pollutant released by mines and other industries.

University of Minnesota researchers are experimenting now with genetically engineered minnows they hope will help eventually reduce mercury in fish, but it’s not a fix for the the mercury that remains embedded in the wetlands and waters of northern Minnesota.

Mercury’s toxic problems

Mercury occurs naturally in the earth’s crust. The element has been used in industrial processes for centuries. For almost as long, humans have known it can be extremely toxic.

The “Mad Hatter” character in “Alice in Wonderland” was inspired by hat makers in the 18th and 19th centuries, who suffered from slurred speech, tremors and other neurological issues from exposure to mercury they used to shape wool felt hats.

Mercury is emitted into the atmosphere when coal and other fossil fuels are burned. It’s also released naturally from volcanoes and forest fires. The mercury that ends up in Farm Lake and other waterways around Minnesota comes from some nearby sources, including giant taconite plants to the south.

Most of it, however, comes from out of state and around the world, swept up into the atmosphere from coal plants, incinerators, gold mines and other industries before it’s deposited in Minnesota as rain and snow, or simply falls to the ground due to gravity.

Mercury only becomes a human health issue — and an issue for wildlife that eat fish, such as loons — when bacteria in wetlands and the sediment at the bottom of lakes convert the mercury to a toxic form called “methylmercury.”

Plankton at the bottom of the food chain pick up the methylmercury as they filter water. Then the mercury works its way up the food chain, accumulating in greater and greater concentrations in larger and larger fish.

“Mercury is extremely bioaccumulative,” explained Nate Johnson, an environmental engineering professor at the University of Minnesota Duluth. “This bioaccumulation process can raise its concentrations by a factor of 100,000 or a million times more in the fish than what there is in the water.”

Children under 15 and fetuses are particularly sensitive to mercury, which can cause lasting problems with understanding and learning, memory and language.

The potential damage is significant. A 2011 study by the Minnesota Department of Health found 10 percent of newborns tested along the North Shore had concerning levels of mercury in their blood.

It’s especially problematic for Native American communities that depend on subsistence fishing for a nutritious diet and to stay connected to traditional tribal lifeways, said Nancy Schuldt, water projects coordinator for the Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Chippewa.

Schuldt recalled a moment several years ago when a tribal elder walked into her office holding a big, foil-wrapped northern pike he had caught in a lake on the reservation. He wanted to know whether he could feed it to his family.

“And the data showed that no, he should not feed that fish to his grandchildren or to his daughter or daughters-in-law who were of childbearing age,” Schuldt said.

Fond du Lac members are encouraged to know which species and sizes are safe to eat, but “that is not a solution to the problem,” Schuldt said. “The solution is reducing the mercury that's going into the ecosystem that is bioaccumulating.”

‘Walleye are mercury magnets’

It seems counterintuitive, but lakes in northern Minnesota, far away from large cities and most industry, generally have far higher concentrations of mercury in fish than in lakes in other parts of the state.

Mucky, microbe-rich wetlands — abundant across much of northern Minnesota, including parts of the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness and Voyageurs National Park — create ideal conditions for mercury methylation, the process that turns mercury toxic.

“Lakes with a lot of wetlands draining into them can have unusually high levels of mercury,” said Dan Engstrom, a retired ecologist who studied the paradox while at the Science Museum of Minnesota’s St. Croix Watershed Research Station.

Another frustrating irony: The pristine nature of northern Minnesota lakes leads to greater concentrations of mercury in fish. Those lakes have fewer nutrients such as phosphorus and nitrogen that are more abundant in lakes elsewhere in the state. That means the lakes also have less algae and less productivity, which results in fewer fish.

“And so if there’s the same amount of mercury and essentially the same amount of mercury that can get into fish, and there's fewer fish, then there’s more mercury per fish,” said Ed Swain, a retired scientist with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Fish also grow more slowly and tend to be older in those lakes, so they tend to have more accumulated mercury in their tissue over time. That includes big walleye, the state fish prized by anglers.

“Walleye are mercury magnets,” said Charles Driscoll, a professor at Syracuse University. “Those types of game fish that are really up at the top of the food chain have the highest concentrations, and they’re often above limits that are safe for consumption.”

Driscoll recently co-authored a study examining lakes in upstate New York where mercury levels in fish are slowly rising. He said forests there and in Minnesota have soaked up mercury like giant sponges since the 1800s.

“And so what’s happening? We’re seeing that [trapped mercury] slowly bleeding out over time,” he said. “So even though the level of accumulation has dropped, which is good, there’s more there than is naturally held under background conditions.”

Minnesota was among the first states to develop a comprehensive plan to reduce mercury in the environment to make those fish safer to eat. The goal set nearly 20 years ago was to cut mercury emissions 93 percent compared to 1990 levels by this year.

The state won’t meet that goal, said Frank Kolasch, assistant commissioner for air and climate policy at the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

That’s in large part due to northern Minnesota’s iron ore mining, which releases mercury from its giant taconite processing plants. They are now the state’s largest mercury emitter. Last month, the Trump administration agreed to delay implementing a plan to cut emissions.

Vexing lessons in chemistry, climate change, zebra mussels

Other pollutants complicate the mercury mess.

Topping the list is sulfate, a chemical compound that’s released into waterways by iron ore mines and other industrial sources, including wastewater treatment plants.

Sulfate accelerates the formation of the toxic mercury that accumulates in fish. Microbes present in wetlands and lake sediments in northern Minnesota breathe in sulfate, and produce methylmercury.

For the past 10 years, volunteer water monitors have sampled lakes downstream of two large taconite mines that emit sulfate, Minntac in Mountain Iron, and Northshore Mining outside Babbitt. They found elevated levels of sulfate miles downstream in lakes in the Boundary Waters and Voyageurs where sulfate concentrations are typically low.

“It really matters, because when the water is so pure like that, small increases in sulfate are really impactful.” said Eric Morrison, a chemist who volunteers with the Northern Lakes Scientific Advisory Panel.

Morrison sees a correlation between the sulfate pollution and high levels of mercury in fish in those lakes, especially in walleye in Crane Lake and Voyageurs’ Sand Point Lake.

Those levels, he said, would rank near the top of the U.S. Food and Drug Administration’s list of most contaminated commercial seafood.

State officials don’t dispute the link between sulfate and increased levels of methylmercury but they say factors such as microbes, sediment and the amount of oxygen in the water can also play a role.

Sulfate is also notorious for damaging wild rice beds. Since 1973, Minnesota has limited sulfate discharges into water bodies where wild rice grows. But research has found that sulfate even at levels below the state’s wild rice standard can produce harmful levels of mercury.

Zebra mussels, an invasive species notorious for their effects on Minnesota lakes, also take some of the blame on mercury.

A study published last year found that walleye in lakes infested with zebra mussels in Minnesota had up to 72 percent higher mercury concentrations than in lakes without the invaders.

It’s likely tied to how zebra mussels form dense mats at the bottom of lakes. The lack of oxygen underneath those mats creates prime conditions for the bacteria that lead to the toxic form of mercury that accumulates in fish.

Because zebra mussels suck all the nutrients out of lakes and deposit them on the bottom as waste, they shift the feeding habits of fish toward the bottom of lakes, where the mercury is.

“So it’s sort of a double whammy,” said Gretchen Hansen, an associate ecology professor at the University of Minnesota and one of the study’s lead authors. “They’re creating these conditions that lead to more mercury being available in the lake, and also concentrating feeding in those exact places.”

Hansen is finishing a second larger-scale study that appears to again document higher mercury levels in lakes with mussels.

Climate change is also accelerating the problem. Warmer water temperatures increase activity of the microbes that form the mercury that accumulates in fish. Research has also linked wildfires to increased mercury methylation because of runoff carrying mercury-laden sediment from burned areas into lakes.

All these findings reflect a tough reality, said Hansen: Humans often don’t have control of toxic pollutants once they’re released into the environment.

“We’re seeing some unexpected interactions with other stressors, like invasive species and climate change,” Hansen said. “That means, even if we roll back emissions, we can’t put the genie back in the bottle. And that is challenging.”

Bioengineered minnows to the rescue?

As Minnesota’s mercury problems slowly grows, researchers at the University of Minnesota are studying a technique they hope could remove the toxic element from fish in Minnesota lakes.

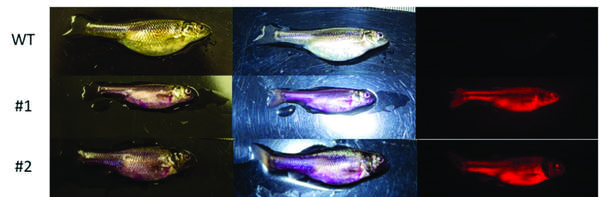

U scientists have developed a process to introduce bacterial genes into fish that essentially reverse the mercury methylation process. It converts the mercury back into a gas, which then escapes the fish back into the atmosphere.

They’ve already proven the concept with zebra fish in the lab. They recently introduced the biotechnology to fathead minnows, a bait fish that’s low in the food chain.

Their hypothesis is that as larger fish eat the minnows, those game fish also won’t accumulate toxic mercury in their tissue.

“In the coming years, we’re going to be testing the efficacy of these genetically engineered minnows in reducing methyl mercury concentrations in their own bodies, but also then reducing methylmercury concentrations in fish that would predate on them,” explained Michael Smanski, the U professor leading the research.

The minnows are sterilized so they wouldn’t spread in the wild, he said.

Researchers are also considering making some of the engineered minnows a fluorescent color — almost to mimic a fishing lure — to see if that would make them more appealing to larger fish.

Smanski stresses the research is being conducted in a controlled lab setting, but they also plan to meet with state regulators to talk through how such a project could be deployed in the real world to remediate mercury in lakes.

“I don’t think that biotechnology is going to be a silver bullet,” Smanksi acknowledged. “We’re not removing mercury from the environment. But it’s going to be integrated with the best approaches from other fields in trying to solve this problem.”

Back on Farm Lake, Dave Setterholm said he’s personally not too worried about eating the fish he catches.

“I’m 73 years old. Something else is going to get me before the mercury does,” he said.

But he added it’s important to continue to try to solve the pollution problem, for young people who love to catch big walleye and pike, and for those who want to have children.

“I think there’s a lot of people who live on the lakes that do fall into those categories,” he said. “And I think they worry about it, and I think they should.”