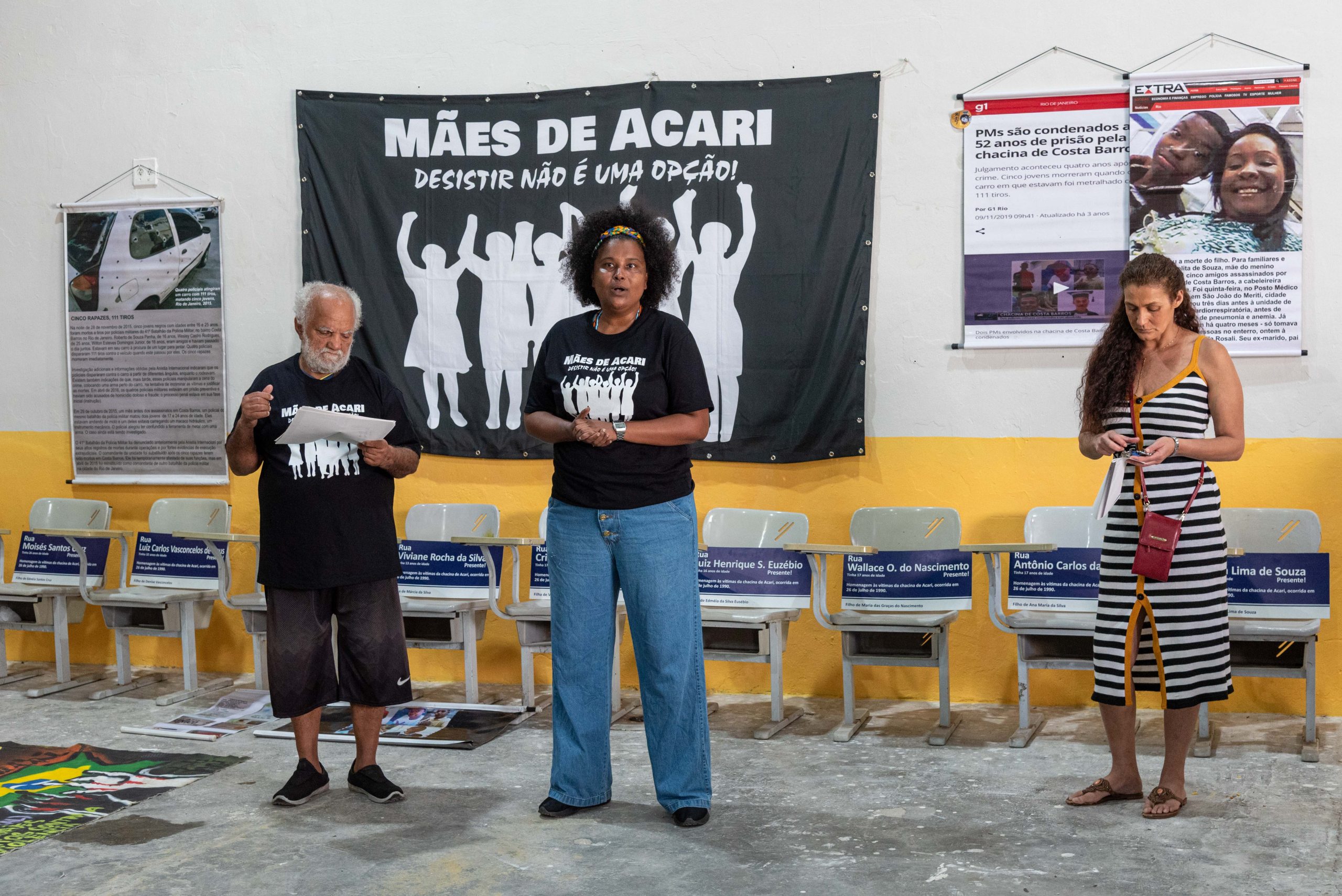

On July 26, 2025, the Fala Akari Collective and the Mothers of Acari Movement held an event marking the 35th anniversary of the Acari Massacre and honoring the ongoing fight for justice for its victims. Hosted at the Mothers of Acari Cultural Space, the gathering brought together around 50 people, including representatives from both collectives, mothers and family members of the victims of the Acari massacre, relatives of victims of State violence from other favelas, lawyers and researchers accompanying the Acari case, parliamentary representatives, and other residents of the Acari favela.

Between Threats, Slander and Reparations, a 35-Year Struggle

On July 26, 1990, Cristiane Souza Leite, 16, Rosana Lima de Souza, 18, Wallace do Nascimento, 17, Edio do Nascimento, 41, Luiz Carlos de Vasconcelos, 37, Moisés dos Santos Cruz, 31, Antônio Carlos da Silva, 17, Viviane Rocha, 13, Luiz Henrique Euzébio, 17, Hudson de Souza, 16, and Edson de Souza, 17, were spending the day at a rural property in Suruí, Magé—a municipality in Greater Rio de Janeiro’s Baixada Fluminense region—when they were forcibly taken by a group of men who identified themselves as police officers.

The kidnappers were after jewelry and money and, after “negotiating” for about an hour (according to Dona Laudicena, a now-deceased witness to the case), took the eleven victims to an unknown location. Their bodies were never found. Since then, the victims’ mothers have been searching for their children and demanding justice—a struggle that has lasted 35 years. They became internationally known as the Mothers of Acari, Acari being the Rio de Janeiro favela where most of the eleven victims lived.

In their efforts to expose the State agents responsible for the massacre, the mothers faced persecution, slander, threats, and a brutal tragedy. Edméia da Silva, one of the leading figures of the Mothers of Acari, was assassinated on January 19, 1993. The men accused of her murder were acquitted in 2024. On July 1, 2022—32 years after the massacre—the Rio de Janeiro Legislative Assembly (ALERJ) passed Law No. 9.753, which mandates financial compensation from the State Government to the mothers of the victims of the Acari Massacre. In 2024, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights found the Brazilian State guilty of the crime.

‘To Make Sure That the Memory of These Young People’s Existence Is Not Lost’

Banners displayed throughout the event space honored the historic struggle of the Mothers of Acari, including posters styled like street signs commemorating the names of the eleven victims of the massacre. The posters also paid tribute to the five young men killed in the Costa Barros Massacre, whose car was shot 111 times by Military Police, along with T-shirts and flags in memory of victims of State violence.

Buba Aguiar, a sociologist, grassroots communicator, and member of the Fala Akari Collective, opened the event by highlighting the importance of holding it on the exact day that marked 35 years since the disappearance of the eleven victims.

“Today we’re holding this event to honor the memory of the eleven young people who were disappeared in what became known as the Acari Massacre… We see the use of forced disappearance by police forces, [which are the] State’s security forces, and by vigilante militias. And that’s yet another connection we’re making: they were victims of forced disappearance by [an] extermination group [called] Cavalos Corredores (Running Horses). With the restructuring of these extermination groups, we have what we today know as the militia [vigilante of-duty police gangs]. There are many ways to murder not only a person’s body, but to try to assassinate—to eradicate—their existence, the memory that they ever even existed. That’s why we’re here today: to make sure that the memory of these young people’s lives, the importance of the struggle of the Mothers of Acari, and of the family members who are still with us, is not lost. Because that’s exactly what the State wants.” — Buba Aguiar

Aline Leite, a relative of one of the victims of the Acari Massacre and a member of the Mothers of Acari Movement, followed with remarks as part of the event’s opening.

“This case devastated many families—families like ours—but also an entire community… all of Rio de Janeiro, and even internationally. But today we are here to speak and to share the memory of the eleven young people who were disappeared in the 1990s at a rural property in Magé… It hasn’t been 35 days, [or] 35 months. It’s been 35 years.” — Aline Leite

The event’s opening was followed by a poetry circle led by Deley de Acari—a cultural producer, writer, activist, and poet from Acari—alongside other residents. Marisa Pinheiro, from Espaço Faveleira, recited a poem by Jurema Araújo that speaks to the pain and anguish of losing a child:

LAMENT (or THE WORLD’S BIGGEST BLOW or THE PAIN OF THE POOR IS SAPPINESS TO INTELLECTUALS and OTHER PSEUDO-OUCHES)

My beloved son I lost

Moving down life’s lonely journey

Tears of aching pain I cry

From a heart so badly broken

I cry my disappeared child

I cry my womb’s lost fruit

Not gone from me in life

But taken by a death too violent

This, no mother can bear

It’s the most hurtful of pains

It’s having your soul all twisted

It’s having a wound that won’t heal

I tread on searching

Trying to freeze time still

Trying to undo the moment

When tragedy swallowed it all

Me? I also died

In that same exact moment

Remembering your face is calming

For my senseless living.

(Poem by Jurema Araújo)

Next, Acari residents and Fala Akari members Buba Aguiar and Letícia Pinheiro introduced the collective, and its various lines of work in the neighborhood.

“[Fala Akari] is a youth collective made up of us—women born and raised in this favela. The main point I think we’ve carried with us all these years is that we do want to call out violations, we do want to talk about violence, but that’s not all we want to talk about. We also want to talk about the possibility of a future. That’s where putting together a community-based college prep course comes from, and where the Agenda Acari project also comes from… The collective uses grassroots media and popular education as strategies so that we, as residents, can truly belong to this place. And there’s the issue of State terrorism, of massacres, of forced disappearances. That shouldn’t be something only the families deal with—it’s a collective issue, something that concerns all of us. So the more we take this history to heart, the more we take the process of these struggles to heart, the more we’re reaffirming our own lives, our own existence, within this territory.” — Letícia Pinheiro

‘They Became Mothers in Search of Their Children’

The discussion circles held during the event aimed to remember the historic struggle of the Mothers of Acari and the legacy they have left for other relatives of victims of State violence. Two mothers were present at the event; the others—some due to age, others because they’ve passed away—were represented by relatives of the victims.

Dona Teresa de Souza, mother of Edson Souza Costa—who was 16 when he disappeared—denounced the lack of answers in a moving statement.

“We’re still here, [but] some parents have already passed without ever knowing anything… They didn’t even leave us our children’s bones so we could bury them with dignity. They vanished. Disappeared. What did they do? To this day, we still don’t know.” — Dona Teresa de Souza

Dona Ana Maria da Silva, mother of Antônio Carlos da Silva—who was 17 when he disappeared—was the other mother present at the event.

Vanine de Souza Nascimento, one of the relatives of the victims of the Acari Massacre, publicly thanked the mothers who never gave up on the fight from the very beginning, when they were first faced with the disappearance of their children.

“We, friends and family, have to thank these women this morning—because it’s thanks to their courage and to them carrying on without even knowing where it would all lead, that we’re here today. They were the pioneers, the starters of this movement [of mothers of victims of State violence in various favelas]—something that, back then, they had no idea would become a movement. They came together and, in 1990, became mothers in search of their children—mothers who dug through the earth with their own hands, mothers who fought and risked their own lives.” — Vanine de Souza Nascimento

Representing the ODH Legal Project, which defends the rights of children, adolescents, and other groups facing social vulnerability, Lucas Arnaud shared an update on the legal proceedings with the mothers and families present. The lawyer spoke about the Brazilian State’s being convicted by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, handed down in December 2024, for the forced disappearance of the eleven victims.

“A crucial acknowledgment was finally made—one that, unfortunately, hadn’t been made until now: that the State is responsible, and that a forced disappearance did in fact occur. This had been a longstanding demand from the families, and while it might sound like a technical issue, it’s actually very significant. It shows that this is truly a cruel act—not only executing sons, husbands, but also disappearing with their bodies… So [after the ruling], little by little, families have been receiving compensation and gaining access to healthcare, which is something crucial that the Inter-American Court demands: that the impacts this whole situation has had on families’ health be acknowledged… And, at the same time, the Inter-American Court calls for another interesting aspect, which is the set of preventive measures—measures meant to stop these cases from happening again.” — Lucas Arnaud

Fábio Araújo, a professor and researcher who studied the Mothers of Acari movement, explained how the struggle of these women was, in many ways, a pioneering one.

“Part of the greatness of the Mothers of Acari movement is that it was a precursor, bringing with it the ability to organize—something that, until then, other groups hadn’t been able to do in order to file these kinds of complaints. And as we heard here today, in many of the stories shared, it’s extremely difficult to speak out when you live in a favela, in close proximity to these [armed police] groups. And in the case of disappearances, there’s the added factor of the absence of a body… You can’t report a killing if there’s no body. And from the point of view… of a business culture, of our State culture, disappearances are treated as events of lesser importance.” — Fábio Araújo

‘What Kind of Democracy Is This?’

Nivia Raposo, from the Movement of Mothers and Relatives of Victims of State Lethal Violence and the Forcibly Disappeared; Patricia Oliveira, from the Network of Communities and Movements Against Violence; and former councilwoman Monica Cunha, co-founder of Movimento Moleque and creator of the Commission to Combat Racism in the Rio de Janeiro City Council, spoke about the importance of the Mothers of Acari’s activism for other mothers and relatives of victims.

“If I am the person I am today, it’s because Vera and Marilene opened the doors… and taught everyone who’s here today—and even those who aren’t—what the struggle of relatives of victims of State violence is. It’s being at a protest, taking part in a public hearing, demanding your rights, drafting a bill. If there’s something we can celebrate in these 35 years, [it’s that the] Mothers of Acari [taught] other mothers and relatives to raise their voices and fight for their rights.” — Patricia Oliveira

Monica Cunha questions the democracy we live in, since the system still allows for forced disappearances and the killing of mostly Black youth in massacres and while allegedly resisting arrest.

“Like Patricia said, the massacres we’re talking about—Acari, Candelária, Vigário Geral, and others—happened after the end of the Military Dictatorship. They happened in a country that calls itself a democracy. But what kind of democracy is this? Just look at the number of massacres. And if we’re going to count the number of people killed or disappeared in this massacre alone. and we know there were others, though we never counted them because we don’t have those figures… [In] a democratic country. So, in this democracy that keeps on killing us, because it hasn’t done a single thing to fight racism, they—and we—are still out here making history. Because today, in this country… if you want to talk about public safety, if you want to talk about this violence, this racism we live with, you have to talk to the families of victims. There’s no book, no scholar or anyone who can speak on this without us. The decisions only happened because we put ourselves out there and said we weren’t going to take it.” — Monica Cunha

35 years later, the Mothers of Acari remain a pioneering movement in the struggles of women whose loved ones were victims of forced disappearances and State violence. With them, a legacy of resistance and persistence was forged—one that has been followed by many other mothers and relatives who have also become victims. In the face of institutional silence that has lasted for decades, these movements continue the fight for memory, truth and justice.

See the Full Album by Bárbara Dias on Flickr:

About the author: Bárbara Dias was born and raised in Bangu, in Rio’s West Zone. She has a degree in Biological Sciences, a master’s in Environmental Education, and has been a public school teacher since 2006. She is a photojournalist and also works with documentary photography. She is a popular communicator for Núcleo Piratininga de Comunicação (NPC) and co-founder of Coletivo Fotoguerrilha.