NASA’s Plan for a Nuclear Reactor on the Moon Could Be a Lunar Land Grab

Spurred by competition from China and Russia, the Trump administration is pushing for nuclear power on the moon by 2030

NASA’s acting administrator Sean Duffy testifies during a congressional hearing on July 16, 2025.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

NASA could soon go nuclear on the moon.

The space agency’s acting administrator Sean Duffy has issued a directive to expedite building a nuclear reactor on the lunar surface. Duffy, a former Fox News host, is also head of the U.S. Department of Transportation, and he took over leadership of NASA in July after the Trump administration pulled its nomination of private astronaut and businessperson Jared Isaacman.

The directive, first reported by Politico, would accelerate NASA’s long-simmering—and, to date, largely fruitless—efforts to develop nuclear reactors to support space science and exploration.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

The space agency has pursued various projects over the years, most recently in 2022, when it awarded three $5-million contracts to companies to craft designs for small space-ready reactors meant for lunar operations in the mid-2030s. Inspired in part by a space policy directive issued by President Donald Trump during his first term, those reactors were intended to produce 40 kilowatts of power—enough to sustain a small office building—and to weigh less than six metric tons. Duffy’s directive is more ambitious: it calls for NASA to solicit proposals for reactors that would yield at least 100 kilowatts of power and be ready for launch by late 2029. The space agency is tasked with appointing an official to oversee the effort within 30 days and to issue its solicitation within 60 days.

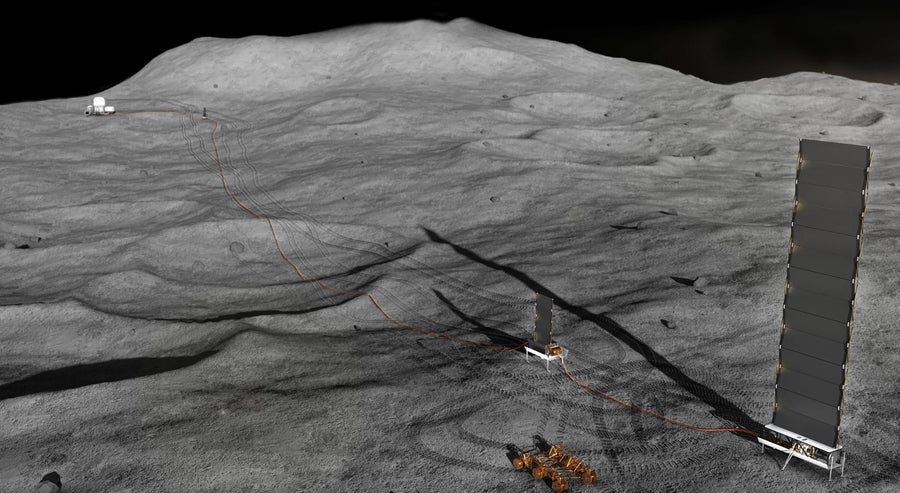

A concept illustration showing NASA’s Fission Surface Power Project on the moon. Under a new directive, the space agency is seeking to develop bigger and more powerful nuclear reactors that could reach the lunar surface by 2030.

Lunar nights are very long—two Earth weeks—and perilously cold, making nuclear power desirable for surface operations. But according to the directive, the greater impetus for the fast-tracked plan is a burgeoning partnership between China and Russia to build a nuclear-powered outpost near the moon’s south pole by the mid-2030s. The sun never crests high above the horizon there, leaving some craters in permanent shadow—and valuable deposits of water ice lacing their eternally dark floors. Despite its cryogenic chill, this lunar region is hotly contested, with NASA’s Artemis program also targeting crewed landings there as early as 2027 as part of the Artemis III mission.

Besides providing abundant electricity for surface operations, a nuclear reactor on the moon could also allow for a strategic lunar land grab. Ownership of otherworldly territory is prohibited, according to the United Nations Outer Space Treaty, but the treaty also obliges spacefaring powers to exercise “due regard” in their activities, meaning that they should not encroach on or interfere with sensitive infrastructure built by others. A nuclear reactor placed on the lunar surface, therefore, could allow the declaration of what Duffy’s directive calls a “keep-out zone.”

Although the Trump administration’s acceleration of NASA’s nuclear-power efforts may be welcomed by many space-exploration advocates, it comes alongside other proposals from the White House that seek to radically reshape the space agency and that could be at cross-purposes with the new directive. These include plans for extraordinarily deep cuts to NASA’s science programs, as well as an active and ongoing culling of the space agency’s workforce. The president’s budget request for fiscal year 2026 notably zeroes out funding for a joint program between NASA and the Department of Defense to develop nuclear rocketry. It would also wind down the space agency’s ability to build and deploy radioisotope power sources, which offer nuclear-derived heat and electricity sans complex and heavy reactors for robotic missions to the outer planets and other sunlight-sparse parts of the solar system.

The biggest question facing NASA’s latest nuclear foray, however, may be what these notional new reactors would actually power. Many experts say a 2027 launch for Artemis III is unlikely and citing factors such as the ongoing difficulties of developing a requisite lunar lander based on SpaceX’s Starship rocket. With each logistical misstep or schedule delay, additional Artemis missions that would put more meaningful and power-hungry infrastructure on the moon slip further over the horizon, potentially making the entire program more vulnerable to additional rounds of budget cuts—or even outright cancellation by future administrations.

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

Before you close the page, we need to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and we think right now is the most critical moment in that two-century history.

We’re not asking for charity. If you become a Digital, Print or Unlimited subscriber to Scientific American, you can help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both future and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself often goes unrecognized. Click here to subscribe.