In the first Ordinary Public Consistory of his pontificate, Pope Leo XIV sets the date for the canonisation of eight Blesseds, including Peter To Rot, the first canonised saint from Papua New Guinea.

By Javier Trapero *

Papua New Guinea’s first saint will be canonised on 19 October 2025, as announced by Pope Leo XIV on Friday, 13 June, in the first Ordinary Consistory of his pontificate.

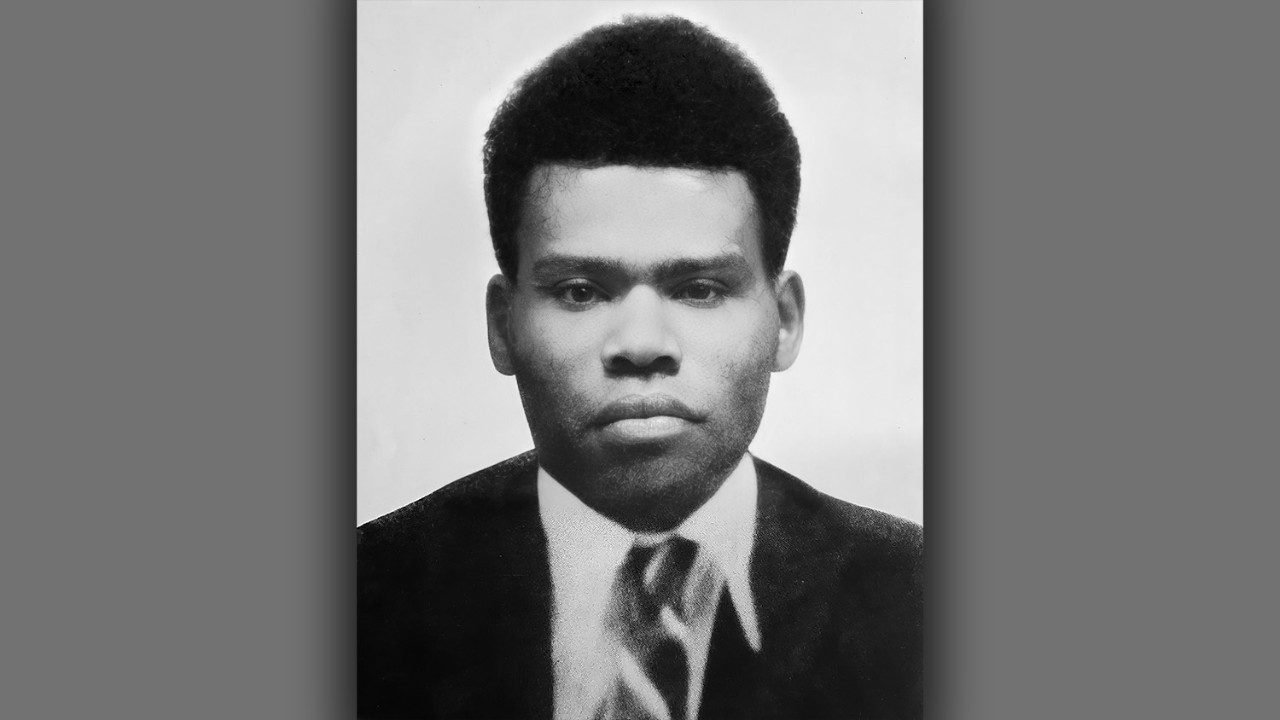

Peter To Rot was a lay catechist who was martyred in 1945 for continuing his apostolate despite a ban imposed by the Japanese. His case is special for several reasons: he will be the first native Papuan saint, a fervent defender of marriage and the family, a catechist committed to the mission of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart. His sanctity is the fruit of the close collaboration of priests and laity in evangelisation.

‘I am in prison for those who break their marriage vows and for those who do not want to see God’s work go forward. That is all. I must die. I have already been condemned to death. These words of Peter To Rot, spoken hours before his death, describe the causes of his martyrdom, but they only make sense with the knowledge and understanding of the many other events that preceded it, without which his deep life of faith and holiness cannot be understood.

Peter To Rot’s parents were among the first natives baptised in Rakanui, his hometown on the New Britain island of Papua New Guinea. This fact, which occurred just 14 years before his birth, gives an idea of the importance of the evangelisation that the missionaries began there at the end of the 19th century, since Peter To Rot’s father was none other than the leader of his people, which meant that his baptism, to the highest authority, was a gesture of acceptance of the message of Christ by the inhabitants of those lands and, perhaps most importantly, the renunciation of all the practices of witchcraft and cannibalism, deeply rooted in their culture. So intense was this conversion to Christianity that Angelo To Puia himself, as he was called, donated the land for the construction of the church, school and house of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart in Rakanui, who had arrived on the island in 1882, sent by Pope Leo XIII, at the express request of the Holy Father to their founder, Fr Jules Chevalier.

As a leader, he was held in great respect by the rest of the population, but even more so for his kindness and personal dedication to those who needed him most. Together with his wife, Maria Ia Tumul, they established a close relationship with the missionaries. In this way, their faith was understood by other members of the community as something good.

It was in this family atmosphere of faith and charity that Peter To Rot was born. From an early age, he offered himself as a servant at Mass, not only at Sunday Mass, but also at daily Mass. It was Carl Laufer, msc, parish priest in that mission since To Rot’s adolescence, who advised him to enter the school for catechists at the age of 18.

The concept of catechists, as well as their functions, in a mission carries with it a strong commitment towards the community. They are true religious and spiritual leaders in charge of keeping the flame of faith alive, carrying out all the activities of a missionary in his absence, with the exception of consecration. They perform baptisms, celebrate marriages, bring the Word… Sometimes their commitment is so great that they even give their lives for it. This was the case in the 1980s in Guatemala, in the region of El Quiché, where dozens of catechists were killed by the army for helping the work of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart, or continuing it when they were expelled from the country.

The circumstances that led to Peter To Rot’s martyrdom were very similar. During World War II, in 1942, the Japanese army invaded Papua New Guinea. One of the first measures they took was to imprison all missionaries, although they continued to allow religious practice by the population. Here, catechists in general, and Peter To Rot in particular, played a very important role in sustaining the faith, celebrations and the dispensation of the sacraments. A year later, they began to prohibit certain activities until, finally, they banned all practice. But Peter To Rot had already made a very strong commitment to the proclamation of the Word of God and to put the teachings of Jesus into practice according to the Gospel.

The Japanese army began to call all catechists to the police station, questioning them about their activities and warning them that the ban on any religious practice was total. Peter To Rot wanted to explain to them that what they were doing had nothing to do with the war, was reprimanded for it and, certainly upset, returned home with the conviction that he had to continue his pastoral work despite the fact that he was practically alone.

He went out in the evenings, in secret, to pray with some groups. He gave a little catechesis and, if necessary, baptised or officiated at weddings. He was well aware that, in the absence of the missionaries, he had to exercise his role as catechist, so as not to leave the Christian communities alone.

As the war drew to a close and the Japanese army was more than likely to be defeated, the Japanese authorities sought to gain favour with the Papuans and revived customs from the past. One of them was polygamy. This led Peter To Rot to fully confirm his commitment to the sacrament of marriage. In addition to the need of keeping the flame of faith alive, there was now the obligation to ensure that these practices, contrary to the teachings of Jesus, now almost banished from the culture of his people, did not return.

He thus began an open crusade against polygamy, which led him to confront certain powerful people, policemen, judges, etc., who wanted to have already married women as wives. To Rot directly confronted the authorities who became his enemies, among them, one with enough power to order his arrest, the policeman To Metapa. He was soon called to testify at the police station about his religious activities. Peter To Rot confirmed that he was still doing what he was supposed to do as a catechist, and when he reaffirmed his stance against the practice of polygamy, they had the perfect excuse to detain him.

During his time in detention, he showed a calm attitude and a clear conviction that he had done well in denouncing the practice of polygamy and defending Christian marriage, as well as continuing his service to the communities. He never showed any regrets and remained firm in his faith and his duties as a catechist.

Finally, in the first days of July 1945, Peter To Rot came down with a cold. There was no need for a firm sentence, no official method of death. Taking advantage of his cold, the doctor gave him an injection and made him take a so-called medicine. After a short while, he felt like vomiting, the doctor covered his mouth and he died.

The policeman To Metapa, who was responsible for his arrest, came to the scene and said: ‘He, the “mission boy”, was very sick and has died’.

* Thanks to the Communications Desk of the Missionaries of the Sacred Heart and Fr. Tomas Ravaioli, IVE.