Welcome to Part 2 of 3 in my consideration of Prescription Drug Pricing in America. You can catch up with yesterday’s Part 1 post here, and Part 2 here.

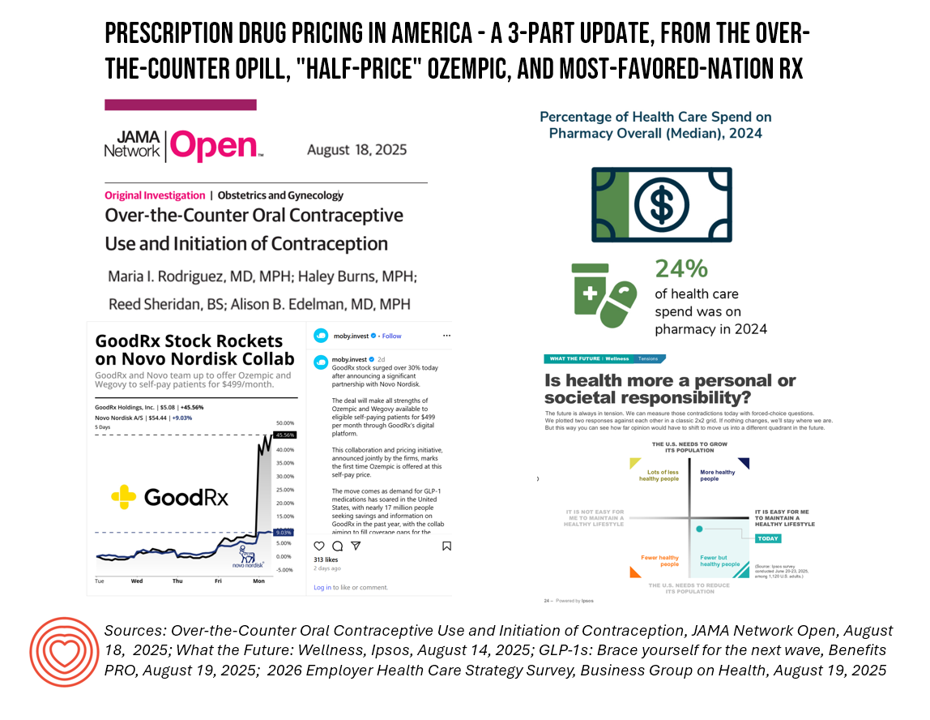

The macro-context for these 3 posts are the forecasts for health care spending for the coming year. Health care cost increases forecasted for 2026 will, in significant part, be driven by prescription drug trend. This graphic from this week’s release of the Business Group on Health’s employer survey on healthcare cost growth to 2026 illustrates a key finding that’s echoed in other similar studies recently released and covered here in Health Populi.

A kay cost-contributor cited in all of these health cost forecasts is the prescription drug line item: specialty drug prices, and more specifically the costs of GLP-1 medicines and cancer therapies.

In this, Part 3 of this week’s 3-part post, I will discuss the Trump Administration’s current intentions to apply “Most Favored Nation” (MFN) approaches to drug pricing in the U.S.

First, a general definition and background on “MFN” — which I learned about in macroeconomics many years ago. It’s a term that comes out of global trade as a pillar of the World Trade Organization (think WHO-for-trade), part of the United Nations organizational ecosystem). The MFN rule is the core principle of the WTO, first coming into force in January 1948. Simply put, MFN in the general context of world trade means that (WTO) members must not be discriminated against; in the absence of a specific free trade agreement (which allow tariffs to be set below the MFN rate), all WTO members enjoy the same treatment as the most favored country.

In the context of prescription drugs, I recommend that you start with the origin story for MFN drug pricing in the words of the White House, here in President Trump’s site on the topic first published in May.

As background to the situation, President Trump action asserts that, “My Administration will take immediate steps to end global freeloading and, should drug manufacturers fail to offer American consumers the most-favored-nation lowest price, my Administration will take additional aggressive action.”

In addition to establishing rulemaking and procedures to launch MFN pricing of prescription drugs, this statement also includes a section on support for direct-to-consumer drug distribution and sales, the likes of which I discussed in post #2 (e.g., the Novo Nordisk/GoodRx plan for Ozempic and Wegovy, etc.).

As for the MFN details, in very broad terms we can expect some of these general policy prescriptions:

- The setting of price targets based on the lowest price for a prescription drug/product in a developed nation (G7, G20, etc.)

- The initial focus would be on Federal U.S. health care programs — namely, Medicare and Medicaid — but this could extend to commercial payors as well

- The MFN price would initially focus on brand-name drugs with no generic or biosimilar competition

- The Administration would ask manufacturers to voluntarily lower the price of drugs to meet MFN target prices in the U.S. At some point if the pharma manufacturers would not make progress on this, the Administration could implement new rules or levy (additional) tariffs — currently 15% on pharma manufacturers operating in the EU that export to U.S. health care.

This is the beginning of the beginning of the MFN and DTC/DTP health care relative to prescription drugs, over-the-counter medicines, and other medical care and products that could be channeled directly to patients without intermediaries. We’re waiting to see how MFN policies will evolve over the coming months, as the Administration converges with other forces in the “dance” — with lobbyists for the industry, consumer advocates, and other stakeholders on Capitol Hill and around state houses around the U.S.

Earlier this week, in a discussion with a smart team from Avalere on MFN, we were advised to consider MFN “not happening in a vacuum….with other policies interacting such as the Inflation Reduction Act, Medicare drug price negotiations, PBM reforms, states pursuing their own drug pricing policies, and a lot ‘swirling’ in drug pricing conversations.”

Oh — and don’t forget about tariffs’ potential impact on pharmaceutical trade especially with EU manufacturers which is another organic discussion already impacting pharma companies’ decision making across their company value chains, geographics, pipelines, and launch plans.

One thing we-know-we-know about drug pricing and where we started this three-part series discussion: health care costs facing employers could reach 10% in 2026, and the pharmaceutical line-item is quite clear in HR plan benefits targets for cost containment. the Business Group on Health’s survey found that pharmacy was a major driver of overall healthcare costs, accounting for 24% of all employer health spend in 2024. And pharmacy costs are expected to grow 11% to 12% in 2026 BFH expects. It’s namely the GLP-1 meds in the focus of employers, all considering how and when to cover the drugs. Furthermore, specialty drugs in general will be in payors’ sites in terms of pricing, access, and prior authorization coupled with AI tactics.

While employers are looking to conserve health care spending and contain costs, we expect additional cost-sharing with employees that also considers “affordability,” confirmed by Brian Kelsey, CEO and President of the Business Group on Health.

“Cost-sharing with employees” means that consumers receiving health benefits through the workplace would bear additional costs for care, and in this case, for prescription drugs (especially considering the high cost of specialty drugs). That then boosts heath consumers’ demand for patient access programs, and services that support patients and caregivers on health care journeys. This calls for manufacturers and other stakeholders involved in consumers’ use of medicines (pharmacies, pharmacists, physicians) to attend to patients’ layers of well-being — physical health (addressed by the prescription therapies) coupled with financial health and mental/emotional well-being. Remembers, even though we’ve focused on drug pricing these 3 days/posts, the topic breathes in a patient’s personal health ecology and larger context for household well-being, household spending, and social health.

For additional brainstorming, check out the Ipsos report on What the Future: Wellness (published 14 August 2025) which offers two thought-provoking scenarios on the future of health care in the U.S. The one pictured here fits well with our lens on individual payment for care (or medicines) versus social responsibility.

Ipsos asserts, “To make Americans healthier, we’ll need to make maintaining health easier…if economic, policy or environmental pressures make healthy living harder, we could drive to a different quadrant. Alternatively, if new policies bear fruit (and vegetables!), opinions could push us further into our existing quadrant” — that is, with fewer healthy people. Keep in mind, for your own scenario and health policy planning, these larger contexts so that the strategies you develop in the midst of uncertainty are as robust as possible given what we don’t know we don’t know.