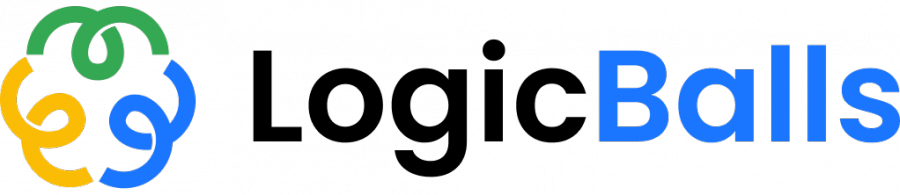

Cuba is the most successful Latin American nation in the history of the Olympics. Despite its small population of 11 million people and geopolitical isolation by its superpower neighbor to the north, Cuba punches well above its weight in sporting terms. Brazil, with a population of 212 million, is the second most successful Latin American nation at the Olympics and, as of 2024, has a mere 170 Olympic medals to Cuba’s 244.

The nation’s success is even more remarkable considering its historic economic misfortunes. The decades-old U.S. embargo has done little to dampen the Caribbean nation’s athletic prowess and the fall of the Eastern Bloc and Soviet Union, devastating as it may have been for Cuba’s economic fortunes, did not slow its athletes down. Since the fall of the USSR in 1991, Cuba has won 192 Olympic medals.

At the Olympic level, Cuba tends to shine in boxing, athletics, wrestling and judo. The island nation also, as of 2024, tops the Olympic baseball medal table, though baseball only became an official Olympic sport at the 1992 Barcelona games and, since 2008, has only featured in one Olympiad.

The Cuban model

Many attribute Cuba’s sporting success to its socialist political model. Joel Leal Ríos, a trainer of the national Cuban female cycling team, certainly does. Ríos told Latin America Reports that Cuba’s socialist system foregrounds masividad, a concept that effectively means the massification of the practice of “all types of sport … in every corner of the country.” As a result, Ríos explains, a small group of elite Cuban athletes is selected from an initial pool of thousands of high-performing athletes to form the national teams.

The National Institute of Sport, Physical Education and Recreation (INDER), the Cuban political body responsible for sport in the nation, was established in 1961, two years after the triumph of the Cuban Revolution. INDER introduced mass physical fitness programs called Listas Para Vencer (LPV), or Ready to Win, to elevate the average fitness of Cuban citizens to military standards. INDER also built sports facilities in rural areas, such as the Escambray Mountains and the Sierra Maestra, to increase popular access to sport in the Cuban provinces.

An illustrative table

Image Source: Camarada de Cuba via X

Fidel Castro, the leader of the Cuban Revolution and Cuba’s political chief from 1959 to 2008, organized a mass re-education program in conjunction with INDER to increase the number of physical education teachers in Cuba. In 1964, INDER organized a summer school where more than 26,000 elementary school teachers were taught basic physical education. The aim of the program was to provide every Cuban elementary school with a qualified P.E. teacher.

Programs like these made physical culture an integral part of Cuban society and helped to broaden the popular appeal of Cuban sport and widen the pool of talent that Ríos identifies as a key factor in Cuba’s international success in sports competitions.

The triumph of Cuban sport, Ríos emphasizes, therefore must be seen as a triumph of the revolution: “it was Fidel who … dedicated his life to … [universalizing] the practice … of sport, making it a right of the people. He was the one who managed to show what a … humble people is capable of when time … and resources are placed at their disposition.”

The political instrumentalization of socialist sport

The sporting success of modern Cuba appears to follow a wider sociopolitical pattern of the incentivization of elite sport by state socialism. In modern history, only socialist nations seem to have been capable of challenging American sporting dominance. Since 1948, the only nations to have unseated the USA at the top of the Summer Olympic medal tables have had some form of socialist government.

The Soviet Union topped the table on six occasions after the 1948 postwar Olympics and also took home the most medals after the collapse of the USSR in 1991, when athletes from the former Soviet Republics competed as the Unified Team at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. China, governed by the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), also topped the medal table in 2008 when the Olympics were hosted in Beijing.

Cuban leader Fidel Castro pictured with three-time Cuban Olympic gold medallist and boxer Teófilo Stevenson before the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics, which Cuba and its Soviet allies boycotted.

Image Source: UJC de Cuba via X

Jenifer Parks, an associate professor of history at Rocky Mountain College, argues that Eastern European nations and the USSR prioritized the development of socialist sporting systems after the Second World War in order “to build a happy and healthy citizenry through mass participation in sports … [and simultaneously promote] a mobilized and disciplined citizenry necessary for the tasks of ‘building socialism’ and and defending the … nation.”

Parks also stresses that popular “participation in sports or mass physical culture promoted [and legitimized] the authority of the [socialist] state.”

The legitimizing political instrumentalization of sport also applies in the Cuban context and explains the Cuban government’s continued investment in sport through periods of dramatic socioeconomic crisis.

Paula Pettavino and Geraldine Pye recognize the seemingly counterproductive prioritization of sport by the Cuban political establishment in their book Sport in Cuba: The Diamond in the Rough, published at the height of the Cuban economic crisis (Período Especial) in 1994. The authors look in particular at the cost of hosting the 1991 Pan-American games in Havana.

“Cuba has overwhelming economic problems, resulting from the near-cessation of aid from the former Soviet Union and Eastern Europe, but the Cuban government still spent an estimated $24 million [USD] (in hard currency) and 100 million pesos ($132 million [USD]) to build athletic and residential facilities for the Pan-American games. [However] the average Cuban has to wait in line for soap, bread, chicken, coffee, and even sugar”.

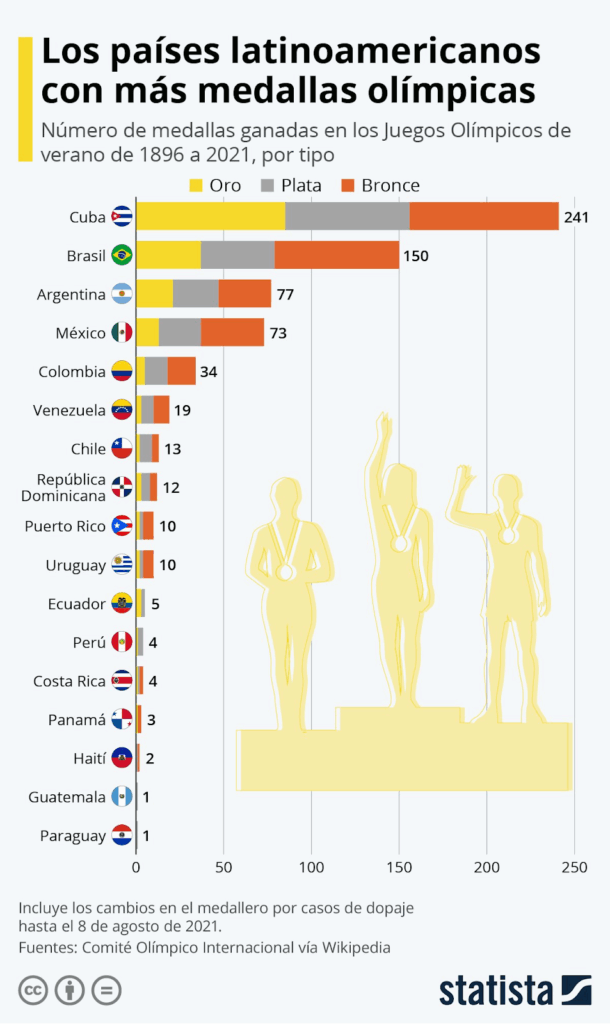

The architect of the Cuban Revolution reiterates the apolitical nature of Cuban sport.

Image Source: Fidel, Soldado de las Ideas via X

Pettavino and Pye assert that Cuban sport serves various socioeconomic, political, military and diplomatic functions. They write that a strong culture of physicality and athletic competition fosters “military preparedness and labor productivity”, allows widely-admired athletes to assist “in the socialization of all Cubans to combat old attitudes that may hinder the development of socialism”, and bolsters state propaganda as Cuban athletic prowess “is among the most recognized successes of the revolution.”

Crucially, Cuba’s physical achievements also oblige “developed countries … to admire Cuban athletic prowess” and encourage “developing countries … [to emulate] the Cuban system [in the hope that that might] … give them similar results”.

El Gigante de Herradura: The story of Cuba’s most decorated sportsman

Mijaín López appears to embody this complementary relationship between Cuban sporting prowess and revolutionary loyalty. Born in the village of Entronque de Herradura in Cuba’s westernmost province, Pinar del Río, López is a Greco-Roman wrestler and indisputably Cuba’s most successful Olympian. He is the only athlete in the world to have won five Olympic gold medals in the same event at five consecutive Olympic games. His most recent Olympic title came at the age of 41 during the Paris 2024 Olympics.

After winning gold at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics (held in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic), López dedicated his victory to “our undefeated Commander-in-Chief [Fidel Castro], who was the one who brought sport to Cuba”.

In December 2024, Cuban revolutionary leader and former President Raúl Castro (brother of Fidel) awarded López the Hero of the Republic of Cuba award and Bartolo, the wrestler’s father, highlighted that, in spite of his son’s many sporting accolades, his “most important medal is his heart, his kindness and the commitment he has to this Revolution, without which he would have been nothing, as the son of poor farmers and a black man.”

López’s dedication to the Cuban Revolution is not limited to rhetoric. He sits as a deputy of the Cuban parliamentary body, the National Assembly of People’s Power, where he represents his native Pinar del Río.

The five-time Olympic medallist is a strict adherent to the party line. He recently criticized the United States for preventing the participation of various Cuban sporting delegations in international competitions held on U.S. soil; López asserted that the White House’s actions amounted to “disrespecting the values of Olympism.”

López also echoed Ríos’ words about the consecration of sport as a popular right in Cuba in the Cuban Parliament last month. López told his fellow deputies that “Sport in Cuba is not politics. Sport is a right of the Cuban people” to raucous applause.

However, López was recently embroiled in controversy. During the 2023 Pan-American games in the Chilean capital of Santiago, the Cuban wrestler and other members of the Cuban delegation – representatives of INDER – at the games appeared to assault a man named Damián Montes de Oca Iglesias, a Cuban resident in Chile.

Cuban President Miguel Díaz-Canel welcomes Cuba’s athletes as they return to Havana after participating in the 2024 Paris Olympics.

Image Source: Gobierno Cuba via X

The incident occurred during a baseball match between Brazil and Cuba. Iglesias, a critic of the Cuban revolutionary government, was holding a Cuban flag emblazoned with the words “Libertad Para Cuba” (Freedom for Cuba). Video footage appears to show the young Cuban being pushed around by representatives of INDER before falling down. After getting back up and confronting the Cuban officials, Iglesias was hit by López.

Charges against López were dismissed by Chilean authorities as Iglesias was reportedly an undocumented resident of the country. However, the involvement of López in the physical altercation is perhaps a fitting metaphor for how sport and politics have been closely intertwined in the history of revolutionary Cuba.

López’s recent golden success notwithstanding, the outlook for Cuban sport today looks bleaker than it ever has in the post-revolution era. Cuba’s medal haul of nine at the 2024 Paris Olympics was its lowest since the 1972 Munich Olympics.

Furthermore, the Cuban government has expressed concern about the possibility of its athletes being barred from competing in the 2028 Olympics in Los Angeles after the Cuban female volleyball team were denied entry visas for a competition in Puerto Rico in July.

Ríos seems to share this pessimism. The cycling coach said that, although Cuba’s sporting policy “today … follows the same [massifying] principle”, the reality is that “poor decisions and the current crisis” mean that the success of old is no longer sustainable in today’s Cuba.

Featured Image: Cuban sporting legend Mijaín López competing in the Men’s Greco-Roman 130kg event against Iranian wrestler Amin Mirzazadeh at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics

Image Credit: mojnews via Wikimedia Commons

License: Creative Commons Licenses