September 8, 2025

3 min read

Rising Temperatures Lead to A Spike in Sugar Consumption

Warmer temperatures are associated with higher consumption of sugary beverages and frozen treats, raising concerns about long-term health effects

Catherine Falls Commercial/Getty Images

When the heat sets in, the siren song of the ice cream truck begins to drift through the air, and lemonade stands run by enterprising neighborhood children pop up along sidewalks. These sweet treats are often synonymous with summer, and a new study has found that sugar consumption in the U.S. rises noticeably as temperatures climb. The increase is particularly apparent among certain groups of people and raises concerns over the health implications as the climate continues to heat up.

Much of the research on global warming and food to date has looked at how changes in the climate affect, for example, crop yields or the nutritional content of food or at how food production and consumption contribute to greenhouse gas emissions. Pan He, an environmental scientist at Cardiff University in Wales, hit on the idea to look at the inverse relationship: how rising temperatures affect food consumption. She and her colleagues decided to focus on sugar because its overconsumption is a known problem in the U.S. and is linked to diabetes, heart disease and certain kinds of cancer.

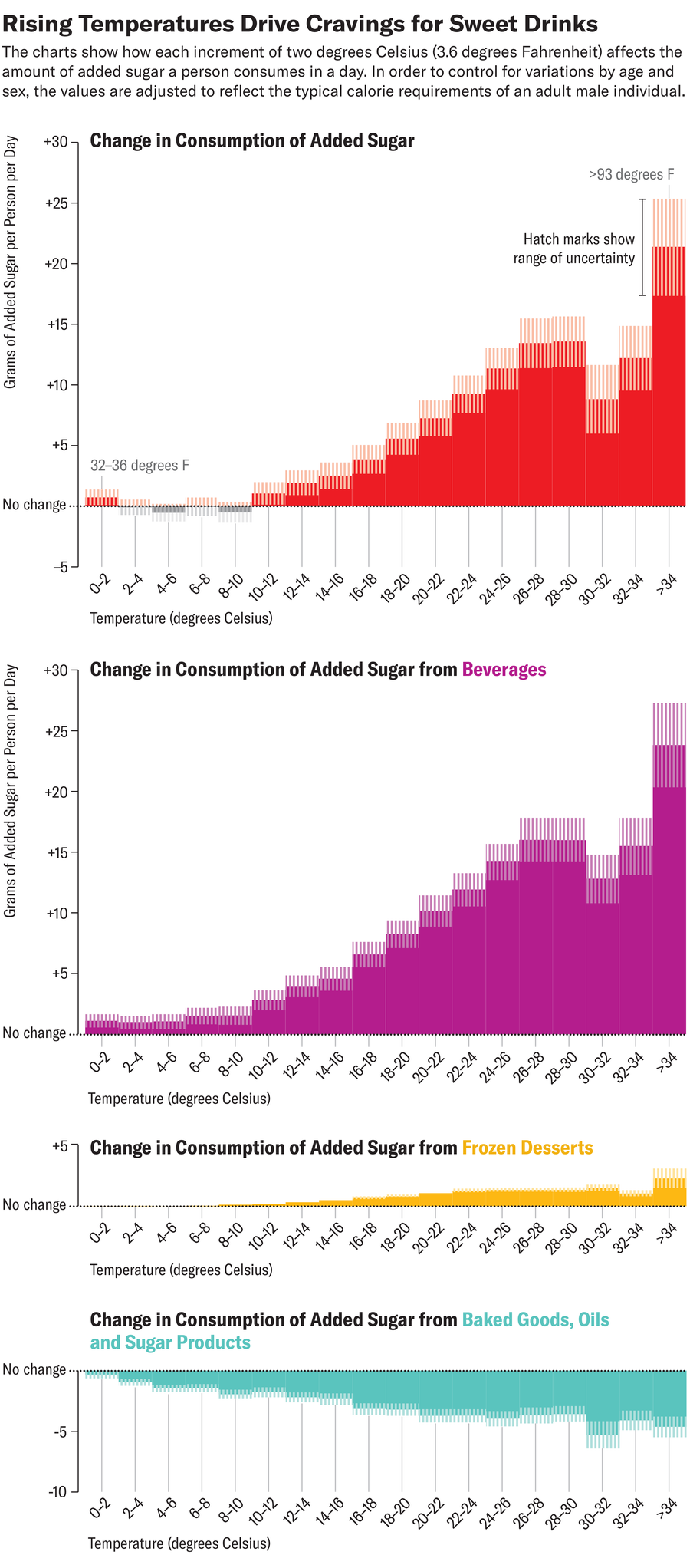

The researchers paired temperature data with a unique dataset that showed household grocery purchases around the U.S. from 2004 to 2019 and used purchases as a proxy for consumption. They found little difference in consumption below 12 degrees Celsius (about 54 degrees Fahrenheit). But between that temperature and 30 degrees C (86 degrees F), something happened: consumption increased by 0.7 gram per degree C. There was a slowdown above 30 degrees C, which the study authors posit could be related to extreme heat often suppressing appetite.

On supporting science journalism

If you’re enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing. By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Most of the overall increase came from beverages with added sugar, such as sodas or fruit drinks, as opposed to 100 percent juice. Frozen desserts such as ice cream or popsicles made a smaller contribution. There was a slight decrease in the consumption of sugary foods such as cakes or cookies, which suggests people may be substituting chilled treats for other options.

The increase is concerning because the average recommended daily sugar intake for a 2,400-calorie diet is about 60 grams—and a single can of soda can have around 40. (The American Heart Association recommends even lower limits of sugar intake each day: 24 grams for women and 36 grams for men.)

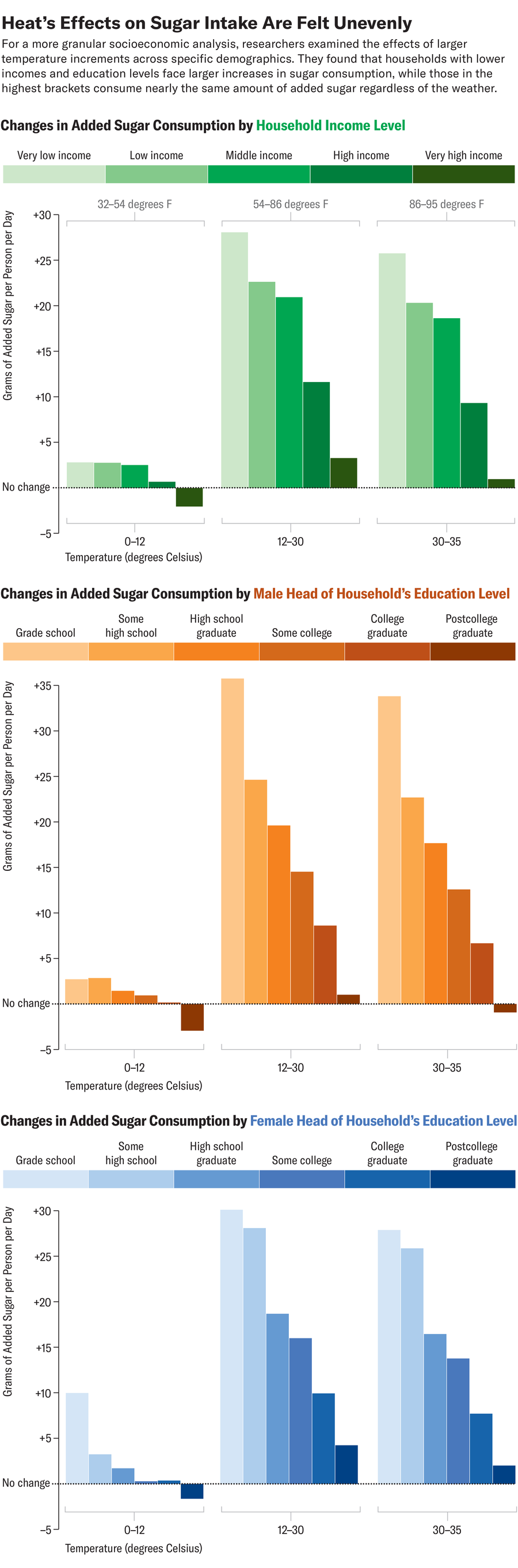

There were noticeable differences in consumption patterns, though. People with higher levels of income or educational attainment showed very little change in sugar consumption as temperatures rose compared with those with lower incomes or less formal education. “The difference can be up to more than five times,” says study co-author Duo Chan, a climate scientist at the University of Southampton in England. “So this is a drastic difference, and I believe this should raise some concerns and awareness among society.”

The difference could be linked to a number of factors: Those with higher incomes often have more reliable access to safely drinkable tap water. They tend to work in indoor environments, where air-conditioning may mean there is less need to stay hydrated. And they may be more aware of the potential health consequences of high sugar consumption.

The researchers projected that, without any interventions, sugar consumption in the U.S. will continue to rise as human-caused warming continues.

Besides addressing the root causes of climate change, ways to tackle this problem could include increasing nutritional education, requiring sugar content to be more prominently labeled on packaging or instituting an added sugar tax. Such a tax already exists in the U.K., and “you see a very, very significant difference” in the price of regular versus diet soda, Chan says. Other strategies could also tackle two problems at once: for example, requiring accessible drinking water and breaks at outdoor workplaces such as farms or construction sites could lower the consumption of sugary beverages—as well as the general risk of heat-related illness.

Alice Lichtenstein, a nutrition scientist at Tufts University, who wasn’t involved with the new study, says she would like to see more research into how the accessibility and pricing of such beverages compare with those of water for disadvantaged groups in attempt to come up with possible interventions. “We need to understand more about what the behavioral triggers are for making negative health-related decisions, such as increased sugar-sweetened beverage intake in hot weather,” she says, “and use that information to design strategies to mitigate the behaviors.”

It’s Time to Stand Up for Science

If you enjoyed this article, I’d like to ask for your support. Scientific American has served as an advocate for science and industry for 180 years, and right now may be the most critical moment in that two-century history.

I’ve been a Scientific American subscriber since I was 12 years old, and it helped shape the way I look at the world. SciAm always educates and delights me, and inspires a sense of awe for our vast, beautiful universe. I hope it does that for you, too.

If you subscribe to Scientific American, you help ensure that our coverage is centered on meaningful research and discovery; that we have the resources to report on the decisions that threaten labs across the U.S.; and that we support both budding and working scientists at a time when the value of science itself too often goes unrecognized.

In return, you get essential news, captivating podcasts, brilliant infographics, can’t-miss newsletters, must-watch videos, challenging games, and the science world’s best writing and reporting. You can even gift someone a subscription.

There has never been a more important time for us to stand up and show why science matters. I hope you’ll support us in that mission.