Mexico has produced a long line of Mexican world boxing champions, most of whom have fought in the lighter weights. Between 1969 to 1985 is considered the golden era for Mexican bantamweights, with Mexico producing nine world champions alone in t hat era.

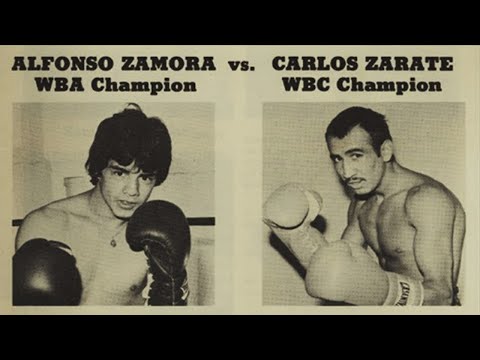

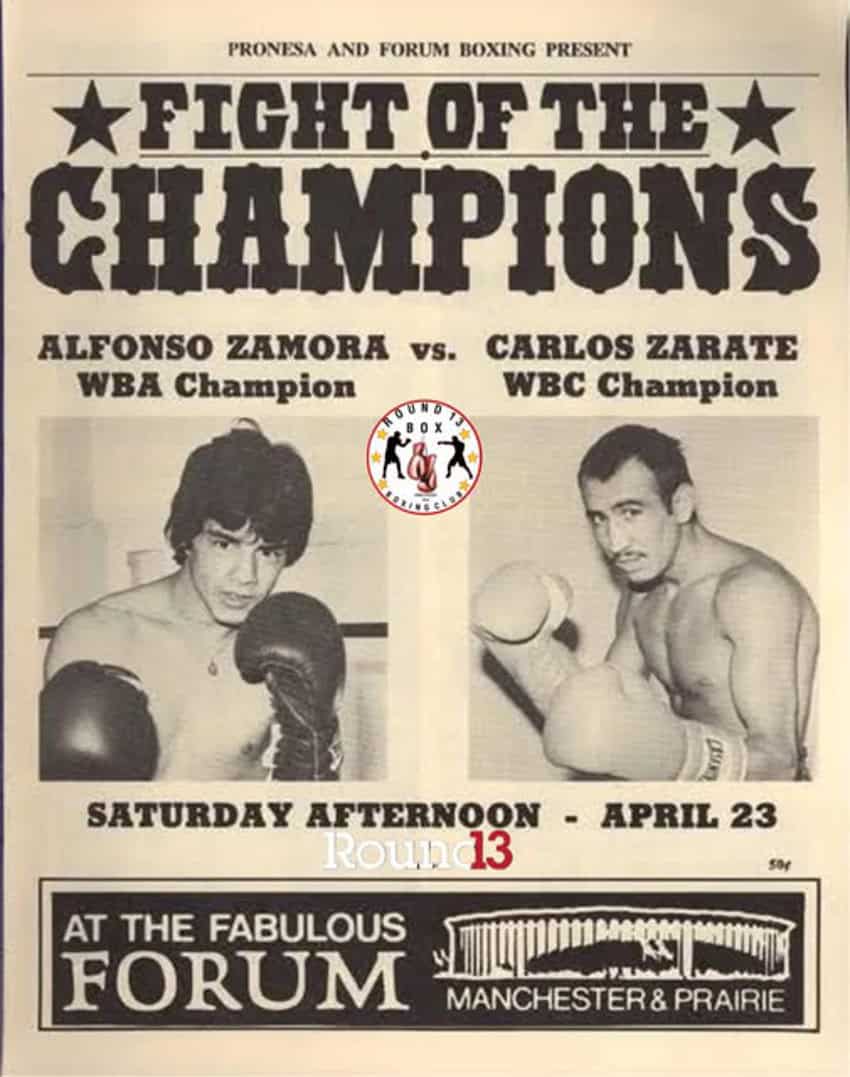

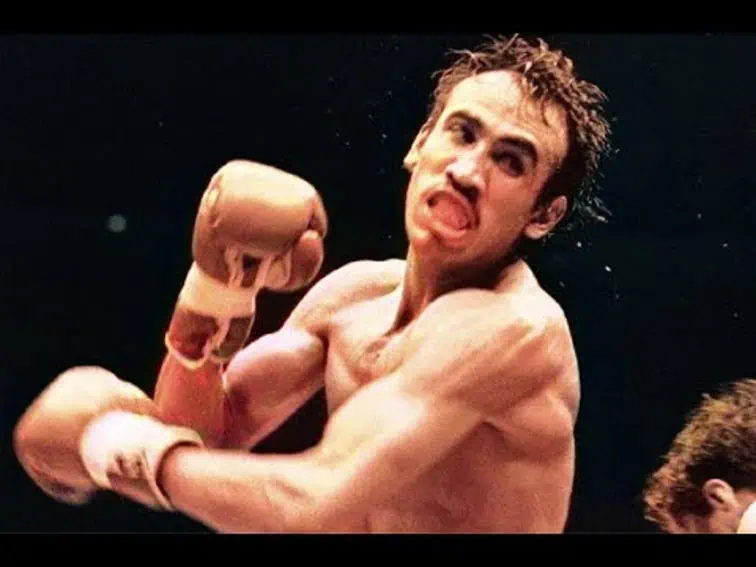

No match during this golden era created as much anticipation as the so-called “Battle of the Z Boys,” the 1977 confrontation between Mexican boxing champions Carlos Zárate and Alfonso Zamora.

Both men came into the fight with world titles — Zárate the WBC title, and Zamora the WBA. Both were undefeated, and both were knockout specialists, who between them stopped 73 of their 74 opponents. So the scene was set for a dramatic showdown.

Friends and boxing stablemates

Zárate and Zamora shared some similarities beyond their raw talent. Both had been born in tough areas of Mexico City: Zárate, the older by close to three years, had been raised in the barrio of Tepito, where fighting and getting in trouble was part of life. Zamora also got into street brawls and had all the other problems of a young boy living on mean streets. Zamora’s father took him to the local gym, where the boy did odd chores and pounded the bag after everybody had left. The coach noticed and started Zamora on his amateur career.

Both men also came through the amateur ranks with distinction: Zárate was a Mexican Golden Gloves champion in 1969 and ended his amateur career with a record of 33 wins and 3 losses. Thirty of his fights had been won by knockouts. Zamora stayed in the amateur ranks until 1972 and was rewarded with an Olympic silver medal at the Munich games. By then, Zárate had won his first 14 professional fights.

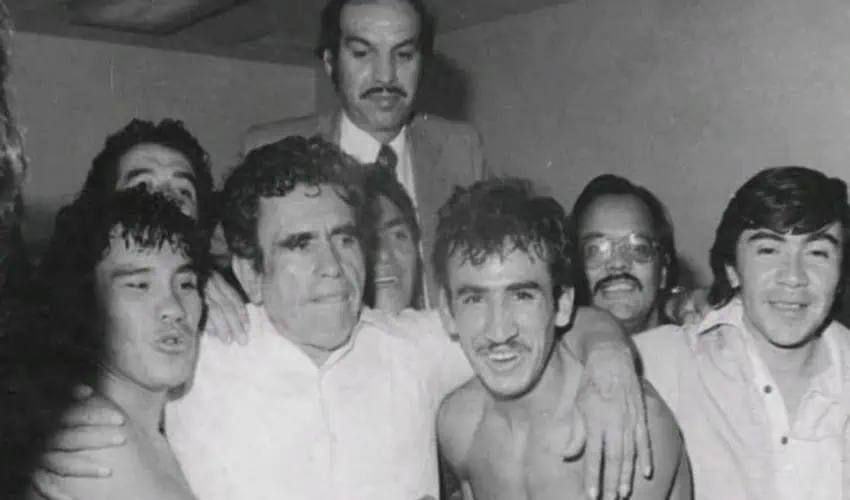

At the start of their careers, both men were managed by Arturo “Cuyo” Hernández, which was hardly surprising, for this was an era when any Mexican boxer with world potential wanted to be in the Hernández stable; he was the forger of Mexican boxing’s world champions, the creator of its bantamweight golden age.

Hernández had been an average fighter, but as a manager he was unequaled. His knowledge, his temper tantrums and his ability to close a deal had guided three of Mexico’s greatest boxers — Rodolfo “Chango” Casanova, José “Toluco” López, and Rubén “Púas” Olivares — to world titles. He had an eye for talent, the vision and the ruthlessness to bring out the best of the young fighters he spotted.

Similar paths, different profiles

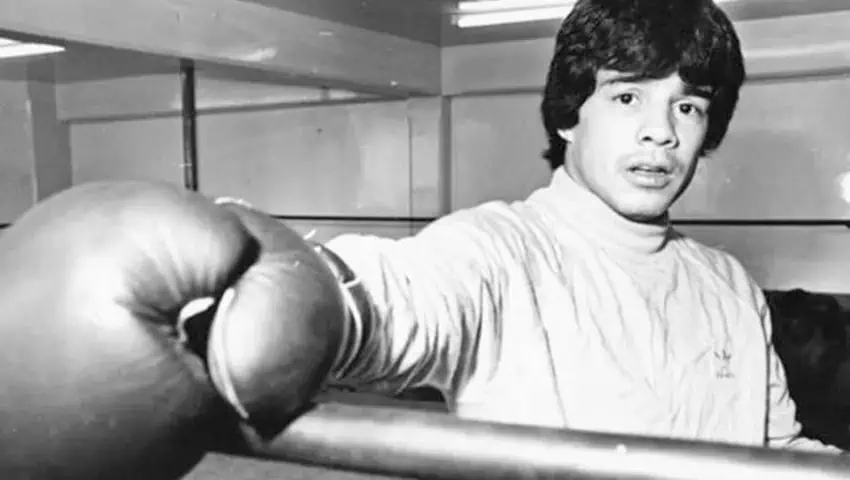

While their careers had followed similar paths, Zárate and Zamora were miles apart in appearance. Zárate stood 1.73 meters (5 feet 8 inches) and had the chiseled build of an athlete. Zamora was shorter at 1.63 meters (5 feet 4 inches), and his power came from a stockiness rather than a bodybuilder’s physique; his strength wasn’t notable until you saw him in action in the ring.

Zamora made his professional debut in April 1973, with a second-round-knockout win over Luis Castañeda. Over the next 13 months, he won 15 fights, all by knockouts, with only one opponent making it past the third round.

This pushed the young Olympic medalist rapidly up the world rankings, and on March 14, 1975, Zamora won the WBA bantamweight title by knockout, defeating Korean Hong Soo-hwan soon after Zamora had celebrated his 21st birthday. He would defend his title five more times before the fight with Zárate, according to a 1976 Sports Illustrated article about the desire among boxing fans to see the two Mexican champions face off in the ring.

On May 8, 1976, Zárate became the WBC world bantamweight champion, knocking out defending champ Rodolfo Martínez in the ninth round. By February 1977, Zárate had made his third successful title defense, stopping Filipino Fernando Cabanela in the third round.

Unsurprisingly, by late 1976, discussions of a showdown between the two Mexican boxing champions were picking up momentum.

A Mexican matchup at Inglewood

Both Zárate and Zamora had won their titles in Los Angeles, at the “Fabulous” Forum stadium in Inglewood, the center of L.A.’s boxing scene, which was one of the world’s most active. L.A. had a significant Hispanic population, so Mexican fighters were always popular there.

The biggest fights also drew fans from across the Mexico-U.S. border. They bought tickets in Tijuana or Mexicali, which gave them trouble-free 72-hour U.S. visas. So there was plenty of excitement in both the U.S. and Mexico at the announcement that the two Mexican bantamweight titleholders would face off at Inglewood.

Surprisingly, however, although the group of businessmen brokering the matchup had promised each competitor a US $125,000 purse, it would not be a title fight. The usual explanation given for this is that neither boxing organization was willing to lose one of their biggest champions. However, unification fights were big business, more courted than avoided, so boxing politics might have been involved.

But we have to wonder if there was concern about one or the other fighter making the weight limit. This nontitle showdown was agreed to with the required weight being at just one pound over the normal bantamweight limit.

Yet, nothing took away from the excitement this matchup provoked. The two managerial teams carried on a war of words in the lead-up to the fight, which was enthusiastically amplified by the Latin American sports media, helping to sell 13,966 tickets. The fighters themselves remained above the nonsense and remained friends in their later lives.

A 4-round disaster

The first round started with Zamora the more aggressive competitor, but Zárate took one of his best punches and stayed steady. Still, Zamora looked dangerous with his counterpunches. With both men known as knockout kings, there was doubt the bout would last long.

“What are the odds of this going the full rounds?” the match’s American commentator asked rhetorically. “You may want 100 to one.”

Zamora started the fight looking for that one winning punch. This might have been confidence, instinct or the fear that Zárate would outlast him if the fight went beyond three or four rounds. Zamora was only 22, but he had already fought 30 professional fights in his lifetime. He later suggested he was not at his best for this fight and might well have been tiring of the routine of daily training.

The fight started out seemingly evenly matched, but by the fourth round, Zamora was no longer able to compensate for Zárate’s superior height and reach.

The second round saw Zárate holding the center of the ring, and while Zamora was throwing out punches, he was not dancing around so much. With a minute to go, Zárate landed a powerful left to Zamora’s chin. The taller man had clearly won the round.

By the third round, as Zamora started to tire, Zárate’s height, reach and boxing skills were putting him in control. The one time Zamora did connect, Zárate brushed it off. By the end of the round, Zamora was knocked to the floor for the first time in the fight. Zamora later recalled that he thought he’d done well for three rounds, after which he didn’t remember much.

Certainly, the fourth round was a disaster for him: Zárate was now the more aggressive, and he dropped Zamora twice, at which point Alfonzo Zamora, Sr. threw in the towel. The white cloth landed over his son’s face, and while that was probably an accident rather than a sign of disrespect, the father was not showing much compassion. With barely a glance at his son lying on the canvas, he strolled across the ring and started a fight with Cuyo Hernández.

Life after the ‘battle’

After this fight, Zamora was never the same fighter. He lost his title in his next fight against Jorge Luján, lost three of his next seven matches and walked away from boxing when he was just 26.

Zárate, in contrast, was at the top of his game for a few years, a man Ring Magazine later summarised as “handsome and well-mannered” and blessed with what the magazine called “his extraordinary punching power that was the soul of his fantastic mystic.”

Zárate won his next five title defense matches — all for big purses — which brought him the good life, including a yacht, an Acapulco apartment and cars. But when he tried moving up a weight category to fight super bantamweight Wilfredo Gómez, Zárate suffered his first defeat.

Coming down with the flu as he arrived in Puerto Rico for the match, Zárate’s team fed him orange juice, but that caused him to put on weight; Zárate had to take saunas and dehydrate himself to make the weight limit. This was probably the one time in his career that Zárate didn’t want to fight, and he was not happy with his manager’s determination to put him into the ring.

After the Gómez fight, Zárate dropped back to bantamweight, and there were two more wins before, in 1979, he stepped into the ring at Caesar’s Palace to face former training partner, Lupe Pintor. Pintor had been fighting well leading up to the fight, but this still looked to be a match well within Zárate’s capabilities. Surprisingly, they went the full distance, with even Pintor looking shocked when the referee raised his arm as the winner.

Like many fighters, Zárate found retirement difficult, made harder by financial problems. After a five-year break, he returned to the ring and had 12 wins in a row, but once he came up against the big names — Jeff Fenech and Daniel Zaragoza — for world title fights, it was clear that age had caught up with him.

There were then problems with drugs, from which the champion finally emerged, thanks to family and religion. He recovered, watched his son and nephew box, and in 1994 was inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame.

Next year will be the 50th anniversary of Zamora and Zárate’s great fight, which will no doubt bring on a flood of nostalgia for an age when Mexican boxers were the world’s best fighters.

Bob Pateman is a Mexico-based historian, librarian and a life term hasher. He is editor of On On Magazine, the international history magazine of hashing.

The post Tales from Mexico’s golden era of boxing: 1977’s ‘Battle of the Z Boys’ appeared first on Mexico News Daily