On Saturday, July 5, the tenth edition of Black July took place at the Maré Museum, in the group of favelas that make up Complexo da Maré, in Rio de Janeiro’s North Zone. The event featured discussion circles led by Black women from favelas and peripheral areas.

Black July is a mobilization that has brought together forces from across the globe since 2016, including Brazil, Palestine, Haiti, Mexico, Chile, Honduras, Colombia, Argentina, India, South Africa, Kenya, and movements like Black Lives Matter, from the United States—international partners united in the fight against racism, militarization, and apartheid in their own communities.

In its tenth edition, Black July 2025 brought together around 50 people for an event organized and led by movements of mothers and family members of victims of State violence, along with favela movements from across Greater Rio de Janeiro. The day featured speakers including: Gizele Martins, journalist from Complexo da Maré; Giselle Florentino, from the Right to Memory and Racial Justice Initiative; Priscilla Ferreira, from multilingual justice initiative Sauti Yetu; Silvio Wittlin, from the Arabs and Jews for Peace Collective; Marcos Feres, from the Palestinian Arab Federation of Brazil (Fepal); Badra El Cheikh, from Sanaúd Youth; family members of victims of State violence from São Paulo, such as Sandra de Jesus, mother of Luiz Fernando, and Maria Cristina Quirino and Danylo Amilcar, mother and brother, respectively, of Denys Henrique; Soraya Misleh, from the Front in Defense of the Palestinian People in São Paulo; and Nicole Burrowes, from the U.S. organization Sister to Sister.

Also present were teachers, activists, and representatives from organizations, collectives, and institutions such as: the Communities and Family Members Against Violence Network; Maré 0800; the Torture Never Again Group (GTNM-RJ); Jubileu Sul; the Institute of Alternative Policies for the Southern Cone (PACS); Mídia 1508; Artvsm; BDS Brasil; the Brazil Chapter of the International Committee for Peace, Justice, and Dignity to the Peoples; the Rio Committee for Solidarity with Cuba and Just Causes; the Movement of Small Farmers (MPA) and Raízes do Brasil; Monica Cunha, former Rio de Janeiro city councilor and founder of Movimento Moleque; the National Network of Mothers and Family Members Victimized by State Terrorism; the Foundation for the Support of Technical Schools (FAETEC); the Anarchist Abolitionist Initiative; the Women of Stone Collective, from Pedra de Guaratiba; the Serra da Misericórdia Integration Center (CEM); the Rio de Janeiro Marijuana March; Fluminense Federal University (UFF); Federal Rural University of Rio de Janeiro (UFRRJ); and the Newark Solidarity Coalition, from New Jersey, USA.

Throughout the event, speakers and participants reflected on the consequences of the internationalization of violence, discussing joint strategies to confront state militarization against its own population. Three panels took place, each documented below: “10 Years of Federal Intervention in Maré,” “Abolitionist Resistances,” and “Resistance Against the Palestinian Genocide.”

‘We Realized the Problem Isn’t Unique to Brazil’

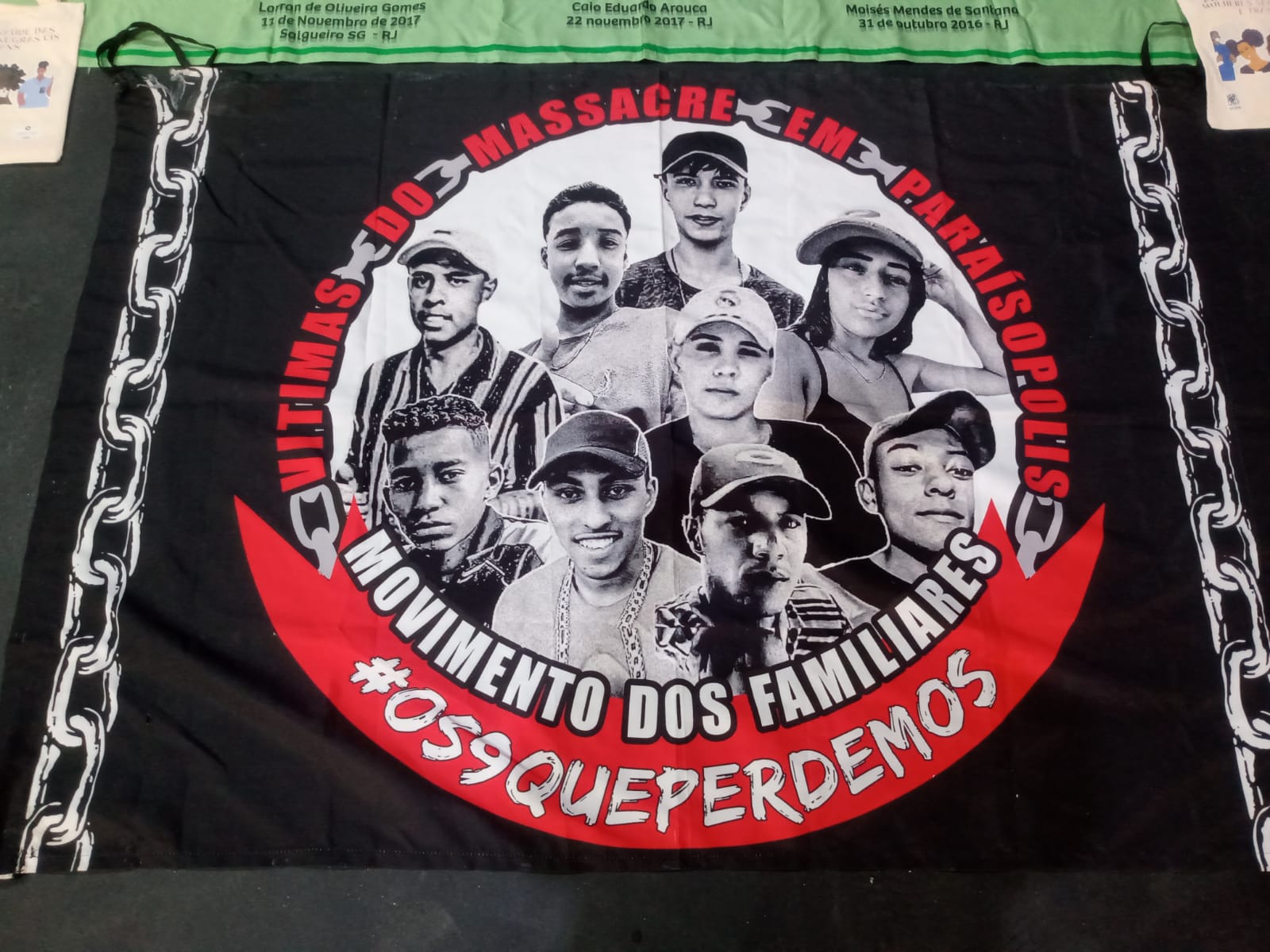

During the panel “10 Years of Federal Intervention in Maré,” Maria Cristina Quirino, mother of one of the youth killed in the 2019 Paraisópolis massacre in São Paulo, emphasized that families—more precisely, mothers—are the first to feel the impacts of this kind of violence. She pointed out how violence is reproduced in similar ways across different regions of the country, and how that led her to become the coordinator behind the project The 9 We Lost.

“The first thing [the authorities] said was [that people had been trampled to death]. But my son’s body didn’t have a single broken bone. I and other family members waited for the response from the Military Police Internal Affairs Division [in São Paulo], and then came the shock: in a statement, they said that the youth over 18 years old were responsible for their own deaths and, in the case of minors—one of them being my son—the parents were the ones to blame. Internal Affairs should have done something, set an example, arrested [those responsible]. Not say that I killed my son. My biggest concern was to show the truth.

A partnership with the São Paulo State Public Defenders’ Office gave me hope [that I’d learn what really happened]. Our children weren’t killed with firearms, but with weapons [the police] claim are non-lethal: beatings, rubber bullets, pepper spray, batons. They were cornered and asphyxiated and died standing in an alley. We were able to prove, in São Paulo, that the 16th Battalion, which was involved in the killing of the boys, is the most lethal—responsible for the most deaths over a ten-year period. [That battalion] was also active during the Military Dictatorship—this disrespect for human rights is historical [when it comes to the local battalion]. We researched the weapons that killed our children and found that they come from Israel. The thing is: funk parties bother a lot of people, and people think the police are the ones who should deal with ‘this problem’. We have to demand an end to this. Enough is enough. I became the investigator of my own son’s case, and today, we are bringing to light a lot of things society doesn’t know—but society must be made aware.” — Maria Cristina Quirino

This struggle is also carried by Sandra de Jesus, mother of Luiz Fernando, who was executed at point-blank range in 2023. Fernando was killed by ROTA (short for Rondas Ostensivas Tobias de Aguiar), the São Paulo Military Police elite squad. His death was officially justified as a shootout—an account that, according to the family, does not reflect what really happened.

“The reality in São Paulo is very different from Rio’s. Here, you have military interventions—we have military training. My son was shot in the back with a burst of seven 7.62-caliber bullets. Why am I mentioning the caliber? Because ROTA is trained by Israel’s military. The São Paulo police buy Israeli weapons and receive training from them. It was not the Israeli bullet that killed my son—it was the training for extermination. The incident reports [for these kinds of cases] are all copy-paste: ‘shootout,’ ‘chase.’ The officers who killed my son are only being prosecuted because I have their bodycam footage. My son was executed with cruelty. I went to that location and found his body on the ground, out in the cold, his cap placed on top of a thermal blanket. The first thing I did as a mother was to apologize, because all the information I had said it was a shootout—and I did not raise my son to do wrong. I did not have the context [of what had really happened]. But when the forensics team arrived, a police officer handed over a weapon that the forensic expert had not found on my son’s body. There is no death penalty in Brazil. The Constitution guarantees the right to life, and that right was denied to my son. So it does not matter what he was doing. We all have the right to make mistakes and to learn from them. The state of São Paulo did not give him the chance to be taken to a police station and serve a sentence. The State does not allow a woman to have an abortion, but we are expected to raise children so they can be executed. That is not fair.” — Sandra de Jesus

She also spoke about how this violence completely changes the lives of mothers.

“When our child dies, we become lawyers, detectives, we have to learn politics, we lose family, jobs, health, income. There is no justice for a mother who lost her child to police violence. Because even if, ten years from now, the State recognizes the execution—with no defense, and denial of medical assistance (it’s on their bodycam footage, including them coercing the doctor)—my Luiz Fernando will not come home to call me ‘mom.’ He will not give me a kiss and say, ‘I love you.’ Today, my dream is to go to law school. I will try to fight as hard as I can, because I want to work by us and for us. There is one thing the State could not—and will not—take from me: being Luiz Fernando’s mother.” — Sandra de Jesus

For Gizele Martins, talking about State violence in Maré is one of many ways to join forces with struggles and peoples around the world who face situations very similar to those in Rio’s favelas.

“Palestinians have traveled the world over the past 70 years of Nakba seeking out social movements with realities similar to theirs. It was during the mega-events in Rio—the World Cup and the Olympics—that we came into contact with the Palestinian movement, and they began showing us that this militarization, this project of controlling territories and peoples, is international. For example, the Brazilian military’s profiling ten years ago [when the favelas were being pacified] was just like the checkpoints in Palestine. The army would search everyone coming in and out of favelas—especially the youth [here in Maré]. The first armored trucks to circulate in Brazil had already been used during South Africa’s apartheid. The new ones are Israeli. So it was through this connection with the Palestinian movement that we realized the problem is not unique to Brazil… These are efficient methods for controlling Black and favela lives. The history of slavery in the favelas has never ended—because there was never any reparation for these areas. The police show up here to control our daily lives—our health, our education, our culture, our community media. Why are there police operations here under the excuse of a War on Drugs? Why are there no police raids on upscale buildings in the formal city, even though people smoke weed there too? Why doesn’t Brazil legalize it? Because it does not want to. The State is making a lot of money behind the scenes. It is not interested in making it up to the mothers [who lost their children]. The State is interested in using us as bargaining chips and in keeping us enslaved. The police’s only job [is to perpetuate violence against the favela], and that will not change. We see the police as [the new] capitão do mato [a slave hunter]—and the media plays the role of criminalizing us. When we stop to think about it, it is all part of a State-designed structure. We need to abolish our police forces and build a society without them. It may seem like a distant dream, but it is possible when we think about the end of slavery.” — Gizele Martins

‘Our Fight Is But One’

During the second panel, “Abolitionist Resistances,” Priscilla Ferreira, from Sauti Yetu, shared reflections on possible paths toward police reform, deconstructing violence and on the concept of policing—starting with interpersonal relationships.

“Policing is not an institution—it is a profession, a form of governance. It is how we internalize things in our imagination, how we deal with conflict. As the capitalist, racist institution it is, the police is one of the expressions of governance supposedly created to regulate class, racial, and patriarchal conflicts. As the relational animals we are, conflict is part of our being together. It shows up in our intimacy. So how do we begin to develop a form of governance that is mutually determined and respectful? How do we start taking responsibility for thinking expansively about what these conflicts are, where they come from, and how we respond to them? We have to think of justice [and the resolution of social problems] in an interdependent way. When we talk about justice, it is not just about incarcerating a murderous cop. We are talking about economic justice, linguistic justice, somatic justice—in relation to the health of our bodies—temporal justice, which is about whether we can manage our own time [among other dimensions].

When we start talking about well-being, we’ll be discussing ‘abolitionisms.’ How many forms of response [solutions] are we capable of creating? How many problems can we intervene in before a [bad] situation happens? When we tell a girl to keep her legs closed because we know the risks of sexism, are we able to intervene [at the root of the problem] before it happens? How do we manage our emotions in an abolitionist way? How do we engage with the other’s body in order to discuss a [romantic] relationship? Can you take on the risk of losing the person you love for not being who they expected—before it turns into feminicide? We tend to think policing begins with hereditary captaincies [a remnant of the Portuguese colonial era, historical and distant from us], but there are many ways to think about policing, starting with ourselves.” — Priscilla Ferreira

During the third panel, Soraya Misleh, Palestinian-Brazilian activist and member of the Front in Defense of the Palestinian People in São Paulo, discussed Brazil’s key role in breaking the cycle of violence in the favelas.

“In the past 20 years, Brazil has become the fifth largest importer of Israeli military technology. These are weapons that are now in the army, used by the Brazilian Air Force. Now, during this phase of the genocide in Gaza, the Brazilian army tried to purchase 36 Israeli armored vehicles for the sum of one billion reais (~US$180 million). The only reason the deal didn’t go through was because we launched a large campaign within BDS—Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions—a movement led by Palestinians to pressure Israel into complying with international law through nonviolent means. We have been denouncing this for a long time: here in Rio, in São Paulo, Santa Catarina, Amazonas… it’s the same [weaponry] that kills Palestinians every day. In 2022, 600 military-grade rifles were purchased [from Israel] by the Rio de Janeiro Military Police, and ended up in the hands of the Special Operations Battalion (BOPE) and the Shock Battalion. This is how the State enters our communities: with the same weapons tested on Palestinian bodies. Our fight is but one. We have to make it echo that this fight is our fight, and that we have to feel like the Palestinian people. We are all Palestinian! We do not need more words. The fundamental step Brazil has to take is to cut ties. That is the step the Palestinian people need. It’s a matter of life or death.” ― Soraya Misleh

Free Palestine! Free Favela!

In the panel “Resistance Against the Palestinian Genocide,” the event’s third and final, Marcos Feres, from Fepal, spoke about the decisive role of international unity in this struggle.

“When we witness the construction of an extermination technology and normalize its use, we’re creating the conditions for it to be used against any other population or in any other conflict… Understanding the Palestinian issue—its level of violence and brutality—is understanding that this pattern will make its way here. Fighting it from here is a matter of survival.” — Marcos Feres

In addition to the discussions, the event featured an artistic and cultural program, including the exhibition “10 Years of Black July,” organized by the Mídia 1508 collective, showcasing records of numerous protests against State violence, and a tribute to Elaine Freitas, a poet and defender of the Black Movement, who passed away during the first edition of Black July, the victim of a sudden heart attack.

Below, read the poem by Elaine Freitas, recited during the event by Fransérgio Goulart, one of the founders of Black July:

Metropolis

The world I see

is split into ghettos –

each piece of the city

under siege

by monotonous soliloquies

its inhabitants

never really seeing each other

though we could define

this territory

by complete surveillance,

the omnipresence of eyes.

Here,

encounters

have

no embraces

(despite the kisses)

and I understand

why I find such pleasure

in being

inside out.

― Elaine Freitas

About the author: Amanda Baroni Lopes is a journalism student at Unicarioca and was part of the first Journalism Laboratory organized by Maré’s community newspaper Maré de Notícias. She is the author of the Anti-Harassment Guide on Breaking, a handbook that explains what is and isn’t harassment to the Hip Hop audience and provides guidance on what to do in these situations. Lopes is from Morro do Timbau and currently lives in Vila do João, both favelas within the larger Maré favela complex.